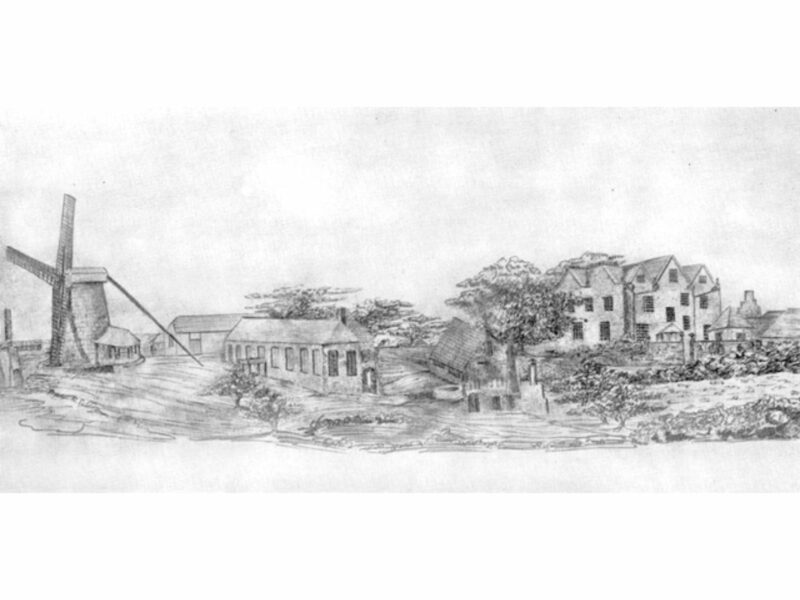

Drax Hall sugar plantation, Barbados, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Barbados’ prime minister, Mia Mottley, is well regarded as a progressive world leader and strong champion of the Caribbean region, outspoken on issues ranging from climate justice to reparations. Her administration’s recent expression of interest in a land purchase from a descendant of slave traders, therefore, struck a sour note, eventually prompting her to address the nation on April 23 and announce that the deal would be put on pause.

To many, the fact that the purchase was even on the table seemed out of step with some of the issues Mottley has taken action on. In late 2020, for instance, amid global Black Lives Matter protests, her government decommissioned a statue of British Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson from its place in Bridgetown’s National Heroes Square because of the role he played in the transatlantic slave trade — a symbolic gesture that spoke volumes about the social temperature of the island — and announced its intentions for self-governance. A year later, Barbados became the world’s newest republic, replacing then British monarch Queen Elizabeth II as the country’s head of state.

Imagine the surprise, then, when the land in question was revealed to be Drax Hall plantation, described by the CARICOM Reparations Commission as a “killing field” for tens of thousands of enslaved Africans who died under horrible conditions between the mid-17th and 19th centuries. British Conservative MP Richard Drax, as the family’s descendant, would stand to be paid GBP 3 million (just over USD 3.7 million) for approximately 50 acres of the estate’s land, which the Barbadian government planned to use for low-income housing developments.

While attorney and political activist David Commisiong, who once headed Barbados’ Commission for Pan-African affairs, acknowledged that “numerous black working-class Barbadians – some of them being descendants of enslaved Africans who were oppressed and exploited on the Drax Hall plantation — [are] desperately in need of proper housing,” he also suggested this must be balanced by the fact that the property was “a central location of the genocidal oppression and exploitation of multiple generations of enslaved black Barbadians” and “the principal generator of wealth for the Drax family […] over a period of hundreds of years” — especially given the history and Drax’s lacklustre response to calls for reparations.

Despite the high-profile efforts of the Trevelyans, a British aristocratic family, to make their own amends for their family’s tainted past and to push for others to do the same, Drax has remained notoriously anti-reparations, calling his family’s involvement in the slave trade “deeply regrettable,” but adding, “no one can be held responsible today for what happened many hundreds of years ago.”

Trevor Prescod, a parliamentary minister who is a member of Mottley’s Barbados Labour Party (BLP) and chair of the Barbados National Taskforce on Reparations, called the decision “a bad example […] How do we explain this to the world?” The UK Guardian reports that Prescod went on to say that “The [Barbadian] government should not be entering into any relationship with Richard Drax, especially as we are negotiating with him regarding reparations.” He was also adamant that if no headway was made in resolving the issue, Barbados would not hesitate to “take legal action in the international courts.”

In speaking with The Guardian back in 2020, Sir Hilary Beckles, the Barbadian historian who chairs the CARICOM Reparations Commission and was instrumental in the signing of a historic agreement for slavery reparations between the University of the West Indies (UWI) and the University of Glasgow — the first such contract since enslaved Africans were fully emancipated by the British in 1838 — did not mince words: “The Drax family has done more harm and violence to the Black people of Barbados than any other family. The Draxes built and designed and structured slavery.”

By late 2022, however, there appeared to be some progress in terms of reparations. Drax reportedly visited Barbados for a meeting with Prime Minister Mottley; there was talk of converting part of Drax Hall into a museum while other areas would be earmarked for low-income housing. Apart from handing over the property as a settlement, Drax may also have been asked to foot the bill for some of the work.

The potential land deal, therefore, threw many observers for a loop, both in Barbados and in Britain. On Facebook, the Sussex Labour Representation Committee wrote, “We agree with Barbados poet laureate Esther Phillips that multi-millionaire MP Richard Drax should be giving up ‘his’ land as reparations for his family’s profiteering from slavery, not further enriching himself at the expense of Barbadians. As socialists and trades unionists, we speak out against this and stand with the people of Barbados.”

Phillips, who grew up next to Drax Hall, called the situation, which she viewed as a case of the descendants of victims compensating a descendant of enslavers, “an atrocity.”

Philip Dunn was of similar mind, saying, “[N]o one should be able to make vast profit today from something inhuman that happened many hundreds of years ago.”

Meanwhile, Barbadian Roland Clarke posted, “While it is intuitive to me that Mr. Drax shouldn’t be legally liable for crimes committed by his ancestors, I cannot say the same for the going concern called Drax Plantation. My view is that Drax Plantation is a ‘corporate person’ under the law. Therefore, like any other ‘person’ who has committed a crime, Drax Planation must face the consequences of the law. [T]he Government of Barbados now seems set to purchase Drax Hall Plantation at market rates. Where are my glasses? Did I read that correctly?”

Many social media users commented on the fact that Drax is one of the richest MPs, to the tune of about GBP 150 million (USD 185,670,000). Cathy Thomas-Bryant added, “I can’t think of any of my friends who wouldn’t simply give the land back to those from whom it was stolen. What an opportunity this man has to do something good rather than something horrible. And no, it isn’t a simple land sale — not when it’s the sale of a plantation that was described as a killing ground, where so many slaves died.”

Caribbean-born Jason Jones, who resides in the UK, was livid: “British Member of Parliament still making money💰 TODAY from his family’s ENSLAVEMENT, rape and murder of Afro-Caribbean people! Tell me again how slavery is in the past and we should ‘just move on’??”

During a 2015 visit to Jamaica, then British Prime Minister David Cameron said he would not entertain any talk of reparations, and advised Jamaicans to “get over slavery.”

Alison Kriel also weighed in with a poignant reminder: “The bank of slave ownership goes on giving. Always remember that the only people compensated post emancipation were the slave owners for loss of revenue.”

As for the position of the Barbados government, Housing Minister Dwight Sutherland, under whose constituency Drax Hall falls, initially explained: “This is an acquisition process at market value. We compensate the landowners. It so happens that this land is owned by Mr. Drax but this has nothing to do with reparations. It is a housing project.”

With Prime Minister Mottley having made calls for reparations as recently as December 2023 in London, however, leaving the issue out of such a sensitive discussion rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. In her subsequent video address, Mottley noted, “We get the concept of reparations both domestically, but also — as we have been doing — internationally,” saying that Barbados has been “at the forefront of making the call for reparations.” She also made a direct link between the climate crisis, a cause she has been very active in, and the “building out” of the Industrial Revolution, funded by profits from the slave trade, which has been the main contributor to greenhouse gas emissions.

In response to comments suggesting that the government should simply seize the land, Mottley unequivocally stated, “Barbados is a country that is governed by the rule of law,” adding she is “not aware of any example where we have expropriated people’s land — when people have land that is the subject of compulsory acquisition, by law we are due to pay for it.”

“At the same time,” she said, “that does not preclude us from going aggressively to be able to pursue [reparations], both through advocacy and [through] legal options.” Sharing that she is “not happy” with the pace at which the reparations discussion has proceeded with Drax, Mottley still cautioned that Barbadians should not “cut off our nose to spite our face,” meaning that citizens in need of housing should not be denied that opportunity.

The prime minister also cited the country’s Tenantries Freehold Purchase Act, which she called “one of the most aggressive forms of land reform in the Americas” and “one of the most perfect forms of reparations,” although it was done “by the people who themselves were the descendants of slaves.” The Act, instituted 40 years ago, allows Barbadians living on plantation tenantries for more than five years to buy the land at affordable prices. The fact that such a measure has not yet been matched by enslavers “in spite of the compensation that they received from the British government — 20 million pounds in hard cash and another 27 million pounds with respect to the forced labour of people between 1834 and 1838 in the apprenticeship system,” Mottley said, “is a matter of grave regret for us.”