One sunny afternoon this June, the artist Betye Saar was surveying a table piled with twigs and branches and strips of bark. In a large shed on the grounds of the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, curators bustled around the 97-year-old Los Angeles artist, offering for inspection materials they had gathered from the Huntington’s 207-acre estate: pieces of eucalyptus, dogwood, kiwi, palm.

Saar was creating a new sculptural installation for the Huntington, which opened to the public on November 11 and will remain on show in the museum’s Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art for two years. “How does it look to you, Betye?” enquired Robert Hori, the Huntington Gardens cultural curator and programme director.

Her white hair pushed up into a lilac baseball cap, clutching a stout walking cane, Saar peered at the display. “It looks like a lot of branches on a table!” she shot back, to laughter. “But we’ll work our magic on it.”

The centrepiece of Saar’s installation, “Drifting Toward Twilight”, is a vintage wooden canoe, 17 feet long, which appears to float a few inches from the ground in the middle of a dimly blue-lit space. Inside the canoe, three bird cages contain antlers; at either end, standing like guards, are heavy carved wooden finials (purchased by Saar from an LA garden store), also adorned with antlers.

Fixed under the canoe’s hull, strips of blue and green neon illuminate the bark and brushwood beneath, arranged by Saar to resemble flowing water. Subtly shifting lighting in the blue-painted gallery mimics the progression of dawn to dusk to night. The atmospheric effect of this immersive environment, as Saar intends it, is of being “at the bottom of the ocean”.

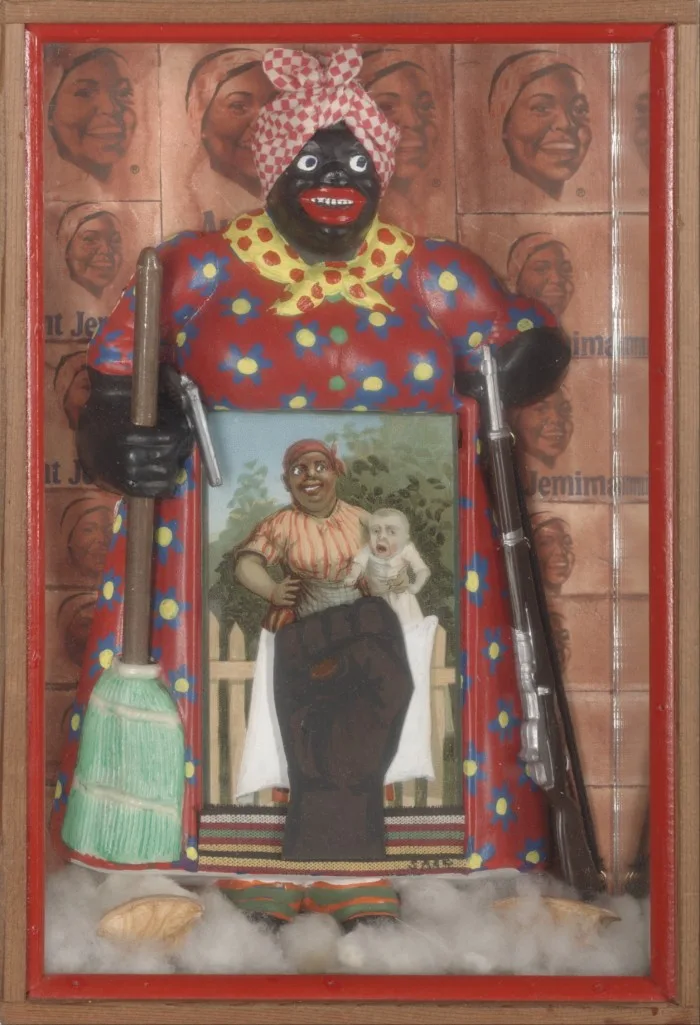

Saar has included ships and boats in her work before. To many, she is best known for her assemblage sculpture and collages, made from found objects and images, which comment on the history of African-American slavery and subjugation. In Saar’s sculpture “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (1972), a figurine of a “mammy” — a racist stereotype of a head-scarfed black servant, the enduring mascot of Aunt Jemima-brand pancakes — clutches a rifle in one hand, and is foregrounded by a fist in a Black Power salute.

That work captures the themes running through Saar’s life and work: domesticity and political activism; feminism and racial politics. In a later installation, “I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break” (1998), she printed a copy of the infamous diagram of the British slave ship the Brookes, which depicts African bodies stacked like cordwood, on to a wooden ironing board. A white sheet, embroidered with the initials “KKK”, hangs on a washing line.

A few weeks after her visit to the Huntington, I am speaking with Saar at her hillside home in Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon, a leafy dell of winding lanes known in the 1960s as a countercultural redoubt. She has lived there since 1962 — before such colourful neighbours as Frank Zappa, Jim Morrison and Joni Mitchell moved in — and raised three daughters there. Her garage and a basement level serve as her studio, and are packed high with half-made sculptures and salvaged materials for possible future works.

I press her on interpretations of “Drifting Toward Twilight”, suggesting a narrative connection between the vessel, the caged antlers and the non-native plants now growing on the former estate of a railway magnate. Is this boat riding the waves of colonial history?

“It’s not that political,” Saar says. “That’s the easiest thing to think of — the ships that brought slaves over. But it’s pre-slavery.” With this installation, she is thinking of timescales grander than the relatively brief history of the US. “I suppose at one time the Huntington was covered with water,” Saar adds. “Most of the world was covered with water.”

She explained that her abiding fascination with canoes began in the 1980s, when she lived beside a lake while teaching at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. Her interest relates, she says, to Indigenous and first peoples’ use of this simple form of transport, which was often carved from a single tree trunk.

Natural materials have always played a role in Saar’s work, alongside human-made found objects. The canoe in “Drifting Toward Twilight” is a wooden sporting model, built in Maine in the 1940s and shipped to the artist from a seller in Florida. Saar has customised it with two gnarled cypress “knees” (lumps that sometimes grow from the tree’s roots) which suggest the profile of a Viking longship, or a galleon with a carved figurehead on its prow.

The commission has additional personal resonance for her: as a girl, she lived in Pasadena, not far from the Huntington, and she remembers visiting the mansion and the gardens with her mother when she was about 13. Today, Saar’s granddaughter Sóla Saar Agustsson works at the institution; she was instrumental in bringing this project to fruition, serving as co-curator with Yinshi Lerman-Tan, the Huntington’s associate curator of American art.

Aside from dugout canoes and slave ships, the other kind of boat that “Drifting Toward Twilight” unavoidably suggests is the ferry that transfers souls between the realm of the living and the afterlife. At 97, Saar has remarkable reserves of energy and mental acuity, but she concedes that she will probably not tackle another installation of this scale and ambition.

For now, though, she is already planning her next projects. Shortly before my visit, she had been beachcombing on the California coast, north of Santa Barbara, and brought home several twisted pieces of driftwood that she was thinking of transforming into snakes: “I just love the idea of finding something and turning it around and making it into art.”

To November 2025, huntington.org