Before the sun came up Dec. 11, 1917, 13 Buffalo Soldiers were marched to the gallows in a military camp near Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. It had been four months since a rampage in Houston left 15 White people and four Black people dead.

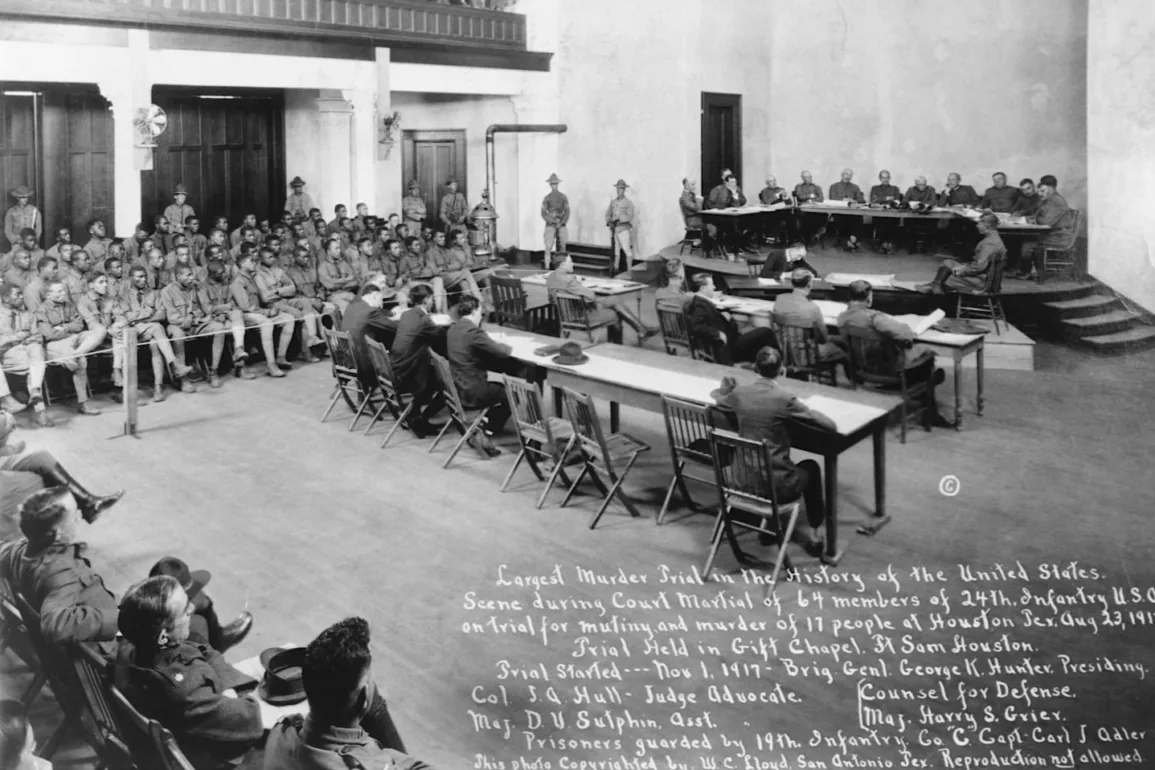

The soldiers of the 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment, an all-Black member regiment, had been hastily convicted of murder and mutiny during the largest court-martial murder trial the country had ever seen.

The 13 soldiers proclaimed their innocence until they ascended the gallows. They had requested to be shot by a firing squad, considered a more honorable way to die in the military. But an all-White jury sentenced them to death by hanging.

One by one that morning, nooses were hung over the gallows, chairs were kicked out from beneath the soldiers, and they dropped to their deaths. The hangings were so swift that not one of the soldiers had been given a chance to appeal for clemency. They were buried in graves with markers indicating only numbers 1 through 13. Later, six more soldiers were executed.

It was one of the largest mass executions carried out in the history of the U.S. Army.

On Monday, 106 years later, the Army formally announced it had overturned convictions of 110 soldiers convicted in the Houston riots. Officials also announced the Army would correct the military records of 95 Buffalo Soldiers who were not restored to duty to show “honorable discharge.” The Army also announced that it would partner with Veterans Affairs to deliver survivor benefits to the soldiers’ descendants.

“Even with the backdrop of entrenched, state-sanctioned racial segregation, there was an immediate public outcry about the miscarriage of justice,” Army Brig. Gen. Ronald D. Sullivan, chief justice of the Army’s Court of Criminal Appeals, told a crowd gathered Monday at the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Houston. He said it led to a major overhaul in the military justice system, establishing due process for service members and a board of review that would later become the Army Court of Criminal Appeals.

The Hon. Gabe Camarillo, undersecretary of the Army, said the Army had undertaken a process to restore their honor. “Today,” Camarillo said, “we are here to deliver on that promise.”

The crowd rose in a standing ovation during a ceremony in which each of the men’s names was read, followed by the tolling of a bell. “For the descendants, the soldiers of 3-24 are not just a list of names or characters in movies,” Camarillo said.

The announcement comes five years after descendants of three of the hanged men — William Nesbit, Thomas Coleman Hawkins and Jesse Ball Moore — petitioned the U.S. government for posthumous pardons, arguing the Buffalo Soldiers had “suffered grave injustices at the hands of the United States when they were executed by hanging after a defective trial by court-martial.”

In 1917, the 3rd Battalion of the 24th United States Infantry had been deployed from New Mexico to Texas to guard construction at Camp Logan, a base that would be built not long after the United States entered World War I.

“The soldiers came to town with patriotism in their hearts, ready to serve their country faithfully,” Sullivan said, “but were met with racist provocations and physical violence.”

In Houston, the sight of Black soldiers carrying guns incensed White people. The soldiers, trained to fight in a war for democracy, were incensed by racist taunts, of being called the n-word, by “Whites Only” signs and by demands by conductors that they sit at the back of streetcars.

The events leading to the infamous Houston Riot began Aug. 23, 1917, when White Houston police officers burst into the home of a Black woman, assaulting her and pulling her — dressed only in her nightgown — into the street, as her five children watched.

When a Black soldier, Army Pvt. Alonzso Edwards, came to the woman’s rescue, he was pistol-whipped by a White officer and then arrested, according to the Texas Historical Commission.

Cpl. Charles Baltimore, one of the most respected soldiers in the regiment, went to the police station to check on Edwards. While there, Baltimore was beaten by police, shot and arrested. He was later released. But by then, false reports had reached the Black soldiers’ camp that Baltimore had been killed.

That’s when 156 Black soldiers of the Third Battalion defied orders to stay in the base and marched to Houston armed with rifles and ammunition.

When the soldiers reached the city, the Black soldiers fought Houston police and local citizens in gun battles. Five White police officers were among those killed. The next day, martial law was declared.

Sixty-three Black soldiers were charged with disobeying orders, mutiny, murder and aggravated assault. The soldiers all pleaded not guilty and were defended by a single man, Maj. Harry S. Grier, who taught law at West Point but was not a lawyer and had no trial experience.

Although 169 witnesses testified for the prosecution during the 22-day court-martial, many could not identify the defendants because the riots unfolded at night during a heavy rain.

Yet on Nov. 28, 1917, 13 Buffalo Soldiers were sentenced to be hanged. Forty-one Black soldiers were given life sentences. Four were given lesser sentences. Five were acquitted. And two more courts-martial were held to try other soldiers.

The men being sent to the gallows were ordered to write letters to their families.

“Dear Mother and Father,” wrote Pfc. Thomas C. Hawkins, “When this letter reaches you I will be beyond the veil of sorrow. I will be in heaven with the angels. I am sentenced to be hanged for the trouble that happened in Houston, Texas. Altho I am not guilty of the crime that I am accused of, but mother, it is God’s will that I go now and in this way.”

A White soldier from Company C of the 19th Infantry later described the gruesome hanging this way:

“The doomed men were taken off the trucks, not one making the slightest attempt to resist,” the soldier wrote. “They were shivering a little, but I think this was due more to the cold rather than fear. The unlucky thirteen were lined up. The conductors took their places and the men for the last time heard the command, ‘March.’ Thirteen ropes dangled from the crossbeam of the scaffold, a chair in front of every rope, six on one side, seven on the other. As the ropes were being fastened about the mens’ necks, big [Pvt. Frank] Johnson’s voice suddenly broke into a hymn, ‘Lord, I’m comin’ home.’ And the others joined him. The eyes of even the hardest of us were wet.”

The hangings of the soldiers, who didn’t have a chance to appeal, provoked outrage across the country. The New York chapter of the NAACP petitioned President Woodrow Wilson for clemency.

In the aftermath, the War Department issued a ruling that “all death sentences be suspended until the President of the United States could review all records.” Wilson would eventually commute the sentences of 10 Black soldiers. And the military reformed the court-martial process, establishing an appeals court.

Angela Holder, a professor of American history at Houston Community College and a relative of one of the Buffalo Soldiers, told The Post in an interview that the overturning of the convictions marked a profound moment in U.S. history.

When Holder was 6 and growing up in Louisiana, she promised her aunt Lovie Ball Kimble that she would find where her aunt’s brother, Cpl. Jesse Ball Moore, had been buried after the 1917 trial.

“They didn’t know where he was buried,” Holder recalled. “They just knew it was in Texas.” Holder remembers a picture of Moore in her aunt’s home, a white wood-framed house in Baton Rouge. “I saw this picture and it caught my attention,” Holder recalled. “I said, ‘Who was that?’ She told me he had been killed by the Army.” There was a deep sadness carved in her aunt’s face.

“She didn’t know where he was buried,” Holder recalled. “In my mind, I said, ‘I’m going to look for him and I’m going to find him.’ ”

Holder spent years researching to find Moore’s grave. Each year since Aug. 23, 2002, she and other descendants of the soldiers would hold commemoration ceremonies in Houston.

“Words cannot express the joy I feel,” Holder said about the overturned convictions. “Having a copy of my uncle’s service record which says, ‘Service terminal by death without honor.’ To know the convictions have been overturned, that will be a relic, an artifact of the past. I’m looking forward to a new document.”

Holder was one of the descendants who spoke during Monday’s ceremony at the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum.

“It was surreal to hear each name called and the bell rung for each of those men,” Holder said. “It was such a beautiful experience that these men were being recognized and they were being restored back to a place of honor.”