BOSTON (AP) — The American legal system is facing a crisis of trust in communities around the country, with people of all races and across the political spectrum.

For many, recent protests against police brutality called attention to longstanding discrepancies in the administration of justice. For others, criticism of perceived conflicts of interest in the judiciary, as well as aspersions cast by former President Donald Trump and others on the independence of judges and law enforcement, have further damaged faith in the rule of law among broad swaths of the public.

Yet many Black attorneys understood the disparate impact the legal system can have on different communities long before the 2020 protests following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police. Many pursued legal careers and entered that same system to improve it, with some rising to one of its most influential roles, the top enforcement official: attorney general.

There is a record number of Black attorneys general, seven in total, serving today. Two Black attorneys, Eric Holder and Loretta Lynch, have served as U.S. attorney general. And the vice president, Kamala Harris, was the first Black woman elected attorney general.

In that same moment of increased representation, the U.S. is gripped by intense debates regarding justice, race and democracy. Black prosecutors have emerged as central figures litigating those issues, highlighting the achievements and limits of Black communal efforts to reform the justice system.

The Associated Press spoke with six sitting Black attorneys general about their views on racial equity, public safety, police accountability and protecting democratic institutions. While their worldviews and strategies sometimes clash, the group felt united in a mission to better a system they all agreed too often failed the people it’s meant to serve.

A spokesperson for Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron, a Republican, did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

All interviewed attorneys general are Democrats. Each attorney general discussed how their backgrounds informed their approach to the law.

“I loved math, and I thought I was going to become an accountant. Clearly, that went a different direction as life happened,” said Andrea Campbell, the attorney general of Massachusetts. She soon began a career providing legal aid in her community because “most of my childhood was entangled with the criminal legal system.”

Anthony Brown and Kwame Raoul learned from their fathers, who were both physicians and Caribbean immigrants. Raoul, now the attorney general of Illinois, said he learned “to never forget where you came from and never forget the struggles that others go through.”

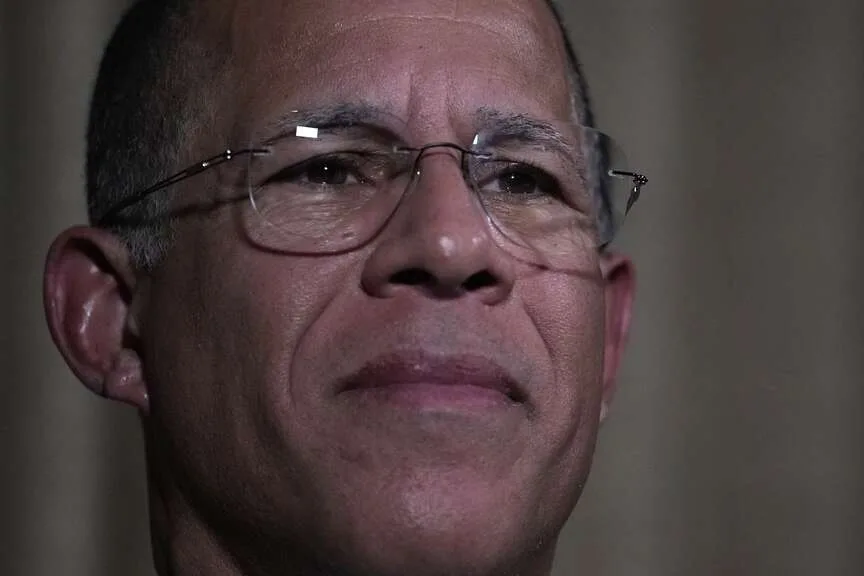

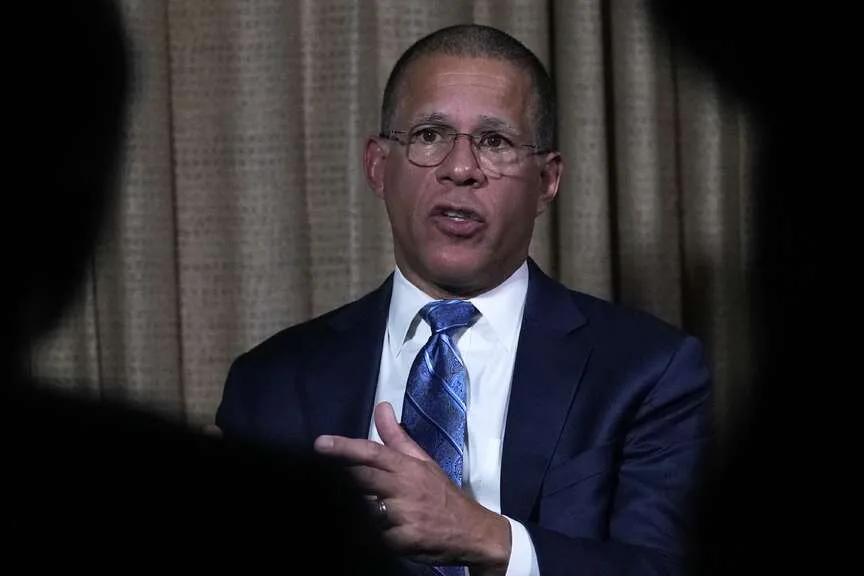

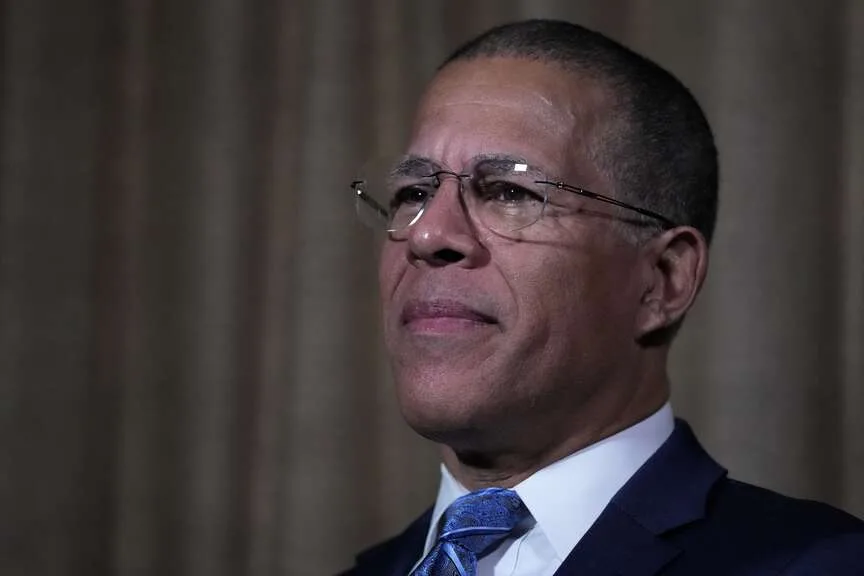

Brown’s father drew satisfaction from knowing that he made a difference in people’s lives and taught him the importance of public service. “I saw that every day as a kid growing up,” said Brown, a retired army colonel now serving as attorney general of Maryland.

Letitia James, the New York attorney general, said she came from “humble beginnings” and was “shaped by those who know struggle, pain, loss, but also perseverance.” Aaron Ford, the attorney general of Nevada, attributed his achievements “because the government helped in a time of need to get to my next level.”

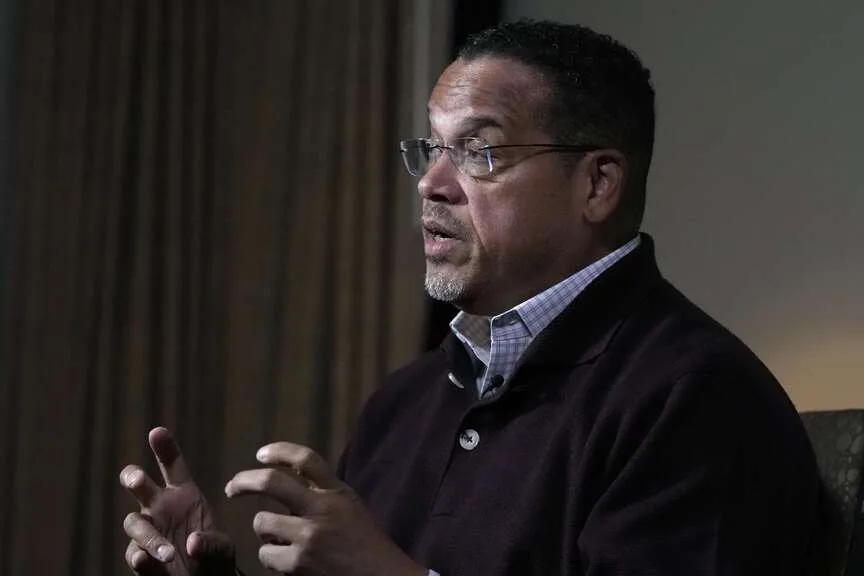

And Keith Ellison, the attorney general of Minnesota, was raised on stories of his grandparents organizing Black voters in Louisiana at the height of Jim Crow, when they endured bomb threats and a burned cross at their home.

“That’s who raised me. Because of that, I have a sensitivity to people who are being punished for trying to do the right thing. And that’s what we dedicate our work to. And there’s a lot more to it,” Ellison said.

On reducing disparities in the criminal justice system

The American criminal justice system is plagued with well-documented inequality and racial disparities at every level. And while an outsized portion of defendants are people of color, prosecutors are mostly white. Many Black prosecutors entered the legal profession to bring the perspective of communities most impacted by the system into its decision-making processes.

“If we are in these roles, I think people expect, and rightfully so, that we will take on criminal legal reform, that we will take out bias that exists in criminal or civil prosecutions, that we will focus on communities of color and do it in such a way that recognizes those communities are often overpoliced and under-protected,” Campbell said.

Efforts at reforming the justice system have been mixed. The disparity between Black and white rates of incarceration dropped by 40 percent between 2000 and 2020, according to a September 2022 report by the Council on Criminal Justice. But while the number of people incarcerated overall across that period slightly fell, policing and sentencing policies vary by state, leading to divergent realities across regions.

Brown has made reducing Maryland’s high rate of Black male incarceration his “number one strategy priority.” Maryland has the highest percentage of Black people incarcerated of any state, though Southeastern states like Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi have higher total populations of incarcerated Black people.

He created a civil rights division in his office and obtained greater powers from Maryland’s general assembly to prosecute police-involved killings and bring such cases under civil rights law.

Both Brown and Campbell said that such reform efforts were in pursuit of both improving equity and law enforcement.

Better prison conditions and fairer justice systems, Campbell argued, reduce issues like recidivism and promote trust in the justice system overall.

“You can have accountability while also improving the conditions of confinement,” Campbell said.

On addressing police misconduct

For Ellison, improving outcomes in the legal system can’t happen without ensuring fair and equitable policing across communities.

“We want the system of justice to work for defendants and for victims both. And there’s no reason it shouldn’t,” Ellison said. He believes involvement from attorneys general is “probably” needed “in order for it to happen.”

Ellison, who successfully prosecuted former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for Floyd’s murder, doesn’t believe such a high-profile case of accountability for police misconduct, by itself, signaled a meaningful shift in police relations with underserved communities.

“One of my big worries after the Floyd case is that now people get to say, ‘Well, you know, we convicted that guy. Move on,'” Ellison said.

Ellison reflected on how his experience as a Black man informed Chauvin’s prosecution. “I knew right off that, based on my life experience, they’re probably going to smear (Floyd),” Ellison said, referencing the various tropes he had expected the defense to use. “If I hadn’t walked the life that I walk, I’m not sure I would have been able to see that coming.”

He also noted no federal policing legislation had been passed since the national protests in the wake of Floyd’s murder. That didn’t mean progress had not been made in Ellison’s eyes, who pointed to various states and local reforms, including in Minnesota, which have enacted higher standards on police training, reforms on practices like no-knock warrants and instituted chokehold bans.

Such changes were often facilitated by Black lawmakers and law enforcement officials. Raoul recalled working on police reform measures with Republican legislators, several of whom were former law enforcement officers.

“Being a Black man in a position of power during that particular time gave me a voice where I was able to get unanimity,” Ford said.

Campbell doesn’t see public safety and racial justice as mutually exclusive.

“You can absolutely make sure that we are giving law enforcement every tool they need, every resource they need to do their jobs effectively, while at the same time taking on the misappropriation of funds, police misconduct, police brutality. All of that can happen at once,” she said.

On protecting democracy and the rule of law

On issues such as voting rights and election interference, Black prosecutors have also drawn national attention for litigating cases examining potential election fraud and voter disenfranchisement.

“I took an oath of office when I got elected to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States and of the state of Nevada,” Ford said. “And I didn’t know that literally meant we’d be protecting democracy in the sense that folks would be pushing back on the legitimacy of our elections and undermining our democracy.”

In the aftermath of the 2020 election, his office litigated six lawsuits against Donald Trump’s presidential campaign and allied groups, which argued without evidence that widespread voter fraud had corrupted Nevada’s elections.

In November, Ford’s office opened an investigation into the slate of electors Nevada Republicans drafted that falsely certified Trump had won the state’s votes in the Electoral College. The lawsuit is the latest in a string of efforts by prosecutors at all levels of government to pursue potential criminal wrongdoing by Trump and his allies in efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

Two Black prosecutors, Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis in Georgia and Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg in New York, are prosecuting cases on related issues, as is a special counsel in the U.S. Department of Justice. The efforts have not come without criticism. Trump has lambasted James, Bragg and Willis with language often evoking racist and stereotypical tropes, such as using terms like “animal” and “rabid” to describe Black district attorneys.

James, who has sued Trump in a civil fraud case in which she argues the real estate mogul misrepresented the values of his assets around the world in financial statements to banks and insurance companies, said Trump tends to use his multiple legal entanglements “as a microphone” to sow more distrust for governmental institutions.

“He unfortunately plays upon individuals’ fears and lack of hope and their dissolution in how the system has failed them. That’s why he’s garnered so much support,” James said of Trump.

“He claims he wants to make America great again, but the reality is that America is already exceptional,” James said. “It’s unfortunate that we are so polarized because of the insecurities of one man.”

On public safety and community needs

Public safety, the cost of living and other material needs are top of mind for most Americans since the coronavirus pandemic caused a spike in crime and economic anxiety. Attorneys general have broad mandates in administering resources, meaning they often can be nimbler in responding to pressing challenges than legislators.

“You don’t solve crimes unless you have communities that trust that they can go to law enforcement,” said Raoul, the Illinois attorney general. “And people don’t trust that they can go to law enforcement if they think that law enforcement is engaging in unconstitutional policing.”

Ellison and James both said a top priority was housing. “We’ve sued a lot of bad landlords,” Ellison said. James said she was focused on real estate investors buying large amounts of working- and middle-class housing across her state, as well as cracking down on deed theft and rental discrimination in New York City.

Ellison has also established a wage theft unit in his office, which he says was informed by the experience of Black Americans.

The prosecutors learn from each other’s crime-fighting techniques but aren’t uniform in their strategies. Ford said he “can’t just do a cut and paste job” for constituencies as diverse as his. But Raoul, for instance, has spearheaded a crackdown on retail store theft in Illinois that Brown has begun to emulate in Maryland.

“We do have significant authority to do a lot at once,” Campbell said. “Divisiveness” at the federal level has prompted many people to turn to local and state officials for action, she said.

On increasing Black representation among prosecutors

Even as the number of high-profile black attorneys in the legal system has risen, many Black lawmakers, district attorneys, attorneys general, and judges are often still a barrier breaker in their communities and, in some cases, the country. While the interviewed officials say they stay in touch with all their peers, they also lean on their fellow Black attorneys general in unique ways.

“Keith Ellison and I served together in Congress. He was an inspiration to me when I was making the decision to move from Congress to the attorney general,” Brown said. The group is in frequent communication through texts, calls and even joint travel domestically and abroad as they build working and personal relationships with each other.

“We have a little group and we’re in regular communication. We boost each other up. We stick with each other and celebrate each other a lot,” Ellison said.

The group views that collaboration as increasingly necessary due to a rising amount of litigation specifically aimed at issues of great interest to Black communities, several attorneys general said.

“There’s an assault going on, an intentional assault against opportunities for the Black community at large and on diversity and inclusion,” Raoul said.

Raoul cited lawsuits against diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in areas ranging from higher education, contracting and employment opportunities as evidence of a “coordinated, well-funded assault on opportunity,” he said. “We cannot be found asleep at the wheel.”

The group also uses their growing size and shared perspective as Black Americans to influence other attorneys general across the country.

“We know that we collectively force a conversation in the (attorney general) community at large simply by us being there,” Raoul said. “That’s not to say we don’t debate with each other, and that’s healthy as well. But we force a conversation that needs to be had.”

James dismissed her barrier-breaking accolades as “nothing more than historical footnote.”

“All that history means nothing to me nor to anyone else. People only look for results,” James said. “Every day I wake up and make sure that I still have this fire in my belly for justice. Sweet, sweet justice.”

Being the first, James said, “doesn’t do anything to feed my soul.”

For most Black attorneys general, the work is ongoing.

“If we’ve made a change, it’s been incremental. I think it would be a little presumptuous of us to think we’ve changed the system,” Ellison said. “We might be changing the system. Hopefully, we are.”

Keith Ellison, Attorney General of Minnesota, answers a question during an interview at the State Attorneys General Association meetings , Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2023, in Boston. In exclusive sit-down interviews with The Associated Press, several Black Democrat attorneys general discuss the role race and politics plays in their jobs. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Anthony Brown, Attorney General of Maryland, listens to a question during an interview at the State Attorneys General Association meetings , Thursday, Nov. 16, 2023, in Boston. In exclusive sit-down interviews with The Associated Press, several Black Democrat attorneys general discuss the role race and politics plays in their jobs. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Anthony Brown, Attorney General of Maryland, answers a question during an interview at the State Attorneys General Association meetings , Thursday, Nov. 16, 2023, in Boston. In exclusive sit-down interviews with The Associated Press, several Black Democrat attorneys general discuss the role race and politics plays in their jobs. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Anthony Brown, Attorney General of Maryland, answers a question during an interview at the State Attorneys General Association meetings , Thursday, Nov. 16, 2023, in Boston. In exclusive sit-down interviews with The Associated Press, several Black Democrat attorneys general discuss the role race and politics plays in their jobs. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Anthony Brown, Attorney General of Maryland, listens to a question during an interview at the State Attorneys General Association meetings , Thursday, Nov. 16, 2023, in Boston. In exclusive sit-down interviews with The Associated Press, several Black Democrat attorneys general discuss the role race and politics plays in their jobs. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Aaron Ford, Attorney General of Nevada, answers a question during an interview at the State Attorneys General Association meetings , Thursday, Nov. 16, 2023, in Boston. In exclusive sit-down interviews with The Associated Press, several Black Democrat attorneys general discuss the role race and politics plays in their jobs. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Aaron Ford, Attorney General of Nevada, answers a question during an interview at the State Attorneys General Association meetings , Thursday, Nov. 16, 2023, in Boston. In exclusive sit-down interviews with The Associated Press, several Black Democrat attorneys general discuss the role race and politics plays in their jobs. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Aaron Ford, Attorney General of Nevada, answers a question during an interview at the State Attorneys General Association meetings , Thursday, Nov. 16, 2023, in Boston. In exclusive sit-down interviews with The Associated Press, several Black Democrat attorneys general discuss the role race and politics plays in their jobs. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Andrea Campbell, Attorney General of Massachusetts, answers a question during an interview at the State Attorneys General Association meetings, Tuesday, Nov. 14, 2023, in Boston. In exclusive sit-down interviews with The Associated Press, several Black Democrat attorneys general discuss the role race and politics plays in their jobs. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)