A researcher typed sentences like “Black African doctors providing care for white suffering children” into an artificial intelligence program designed to generate photo-like images. The goal was to flip the stereotype of the “white savior” aiding African children. Despite the specifications, the AI program always depicted the children as Black. And in 22 of over 350 images, the doctors were white.

Midjourney Bot Version 5.1. Annotation by NPR.

Midjourney Bot Version 5.1. Annotation by NPR.

It seemed like a pretty straightforward exercise.

Arsenii Alenichev typed sentences like “Black African doctors providing care for white suffering children” and “Traditional African healer is helping poor and sick white children” into an artificial intelligence program designed to generate photo-like images.

His goal was to see if AI would come up with images that flip the stereotype of “white saviors or the suffering Black kids,” he says. “We wanted to invert your typical global health tropes.”

Alenichev is quick to point out that he wasn’t designing a rigorous study. A social scientist and postdoctoral fellow with the Oxford-Johns Hopkins Global Infectious Disease Ethics Collaborative, he’s one of many researchers playing with AI image generators to see how they work.

In his small-scale exploration, here’s what happened: Despite his specifications, with that request, the AI program almost always depicted the children as Black. As for the doctors, he estimates that in 22 of over 350 images, they were white.

Alenichev’s work is part of a broader study of global health images that he is conducting with his adviser, Oxford sociologist Patricia Kingori. For this experiment, they used an AI site called Midjourney, because their reading suggested it was good at producing images that looked very much like photos.

Alenichev didn’t just put in one phrase to see what would happen. He brainstormed ways to see if he could get AI images that matched his specifications, collaborating with anthropologist Koen Peeters Grietens at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp. They realized AI did fine at providing on-point images if asked to show either Black African doctors or white suffering children. It was the combination of those two requests that was problematic.

So they decided to be more specific. They entered phrases that mentioned Black African doctors providing food, vaccines or medicine to white children who were poor or suffering. They also asked for images depicting different health scenarios like “HIV patient receiving care.”

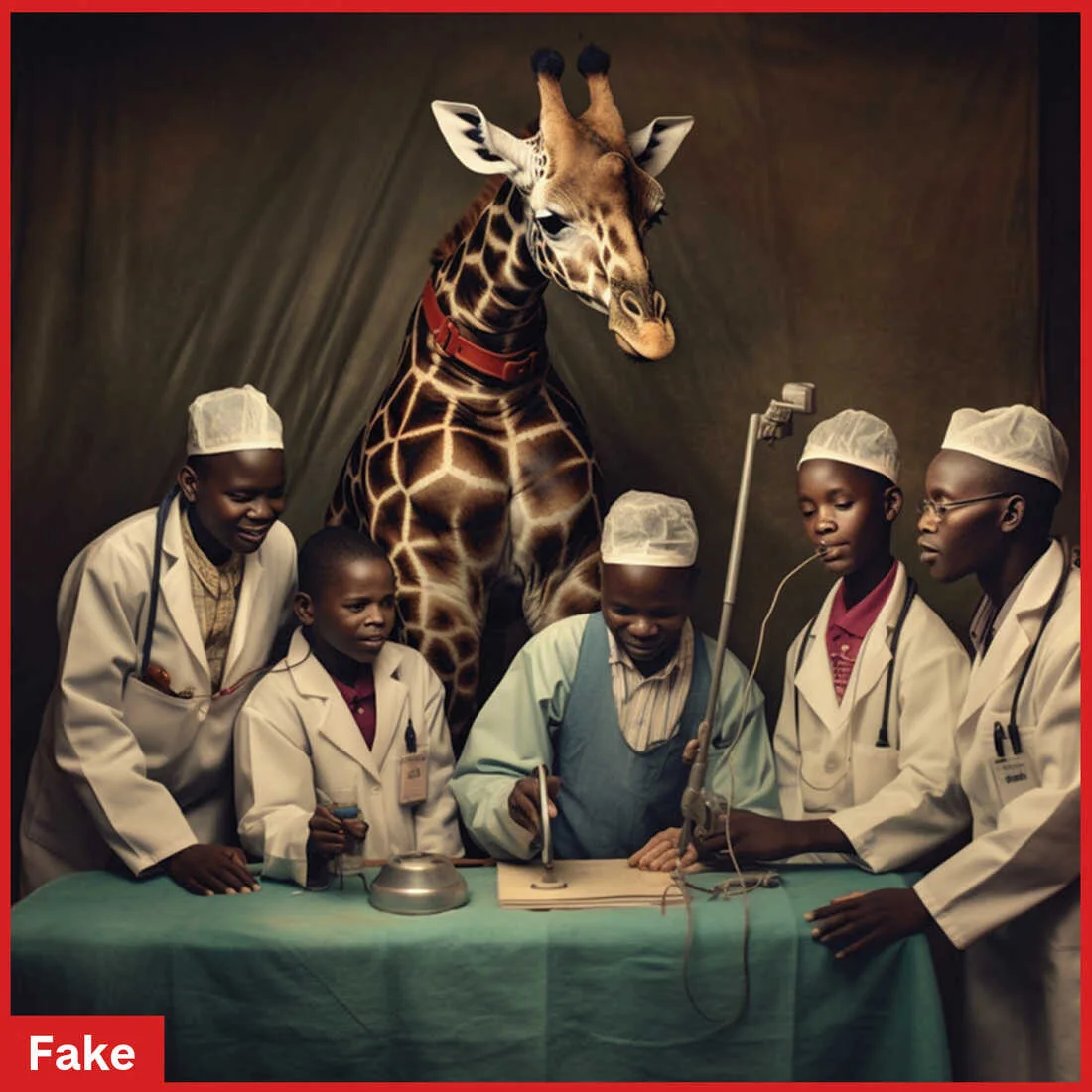

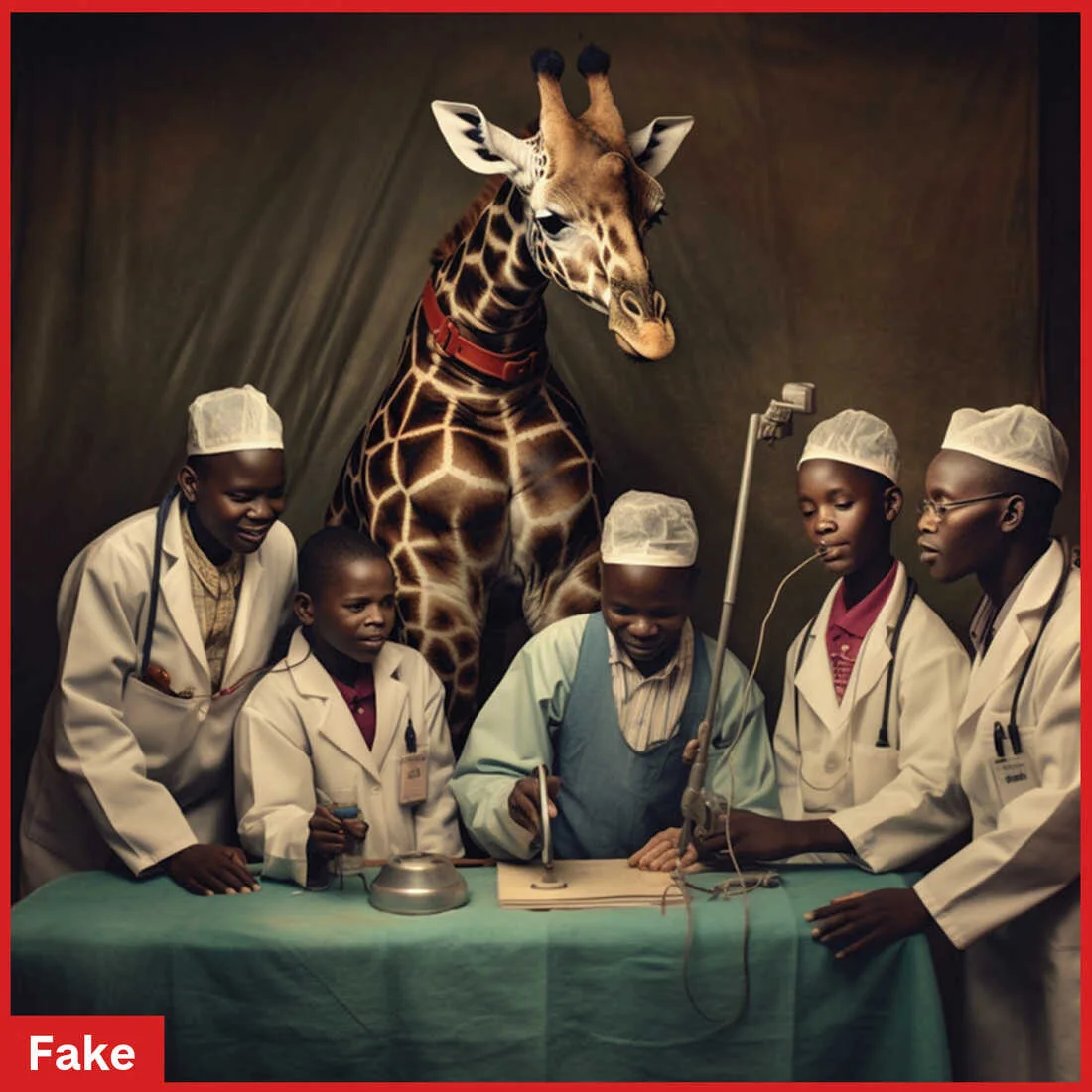

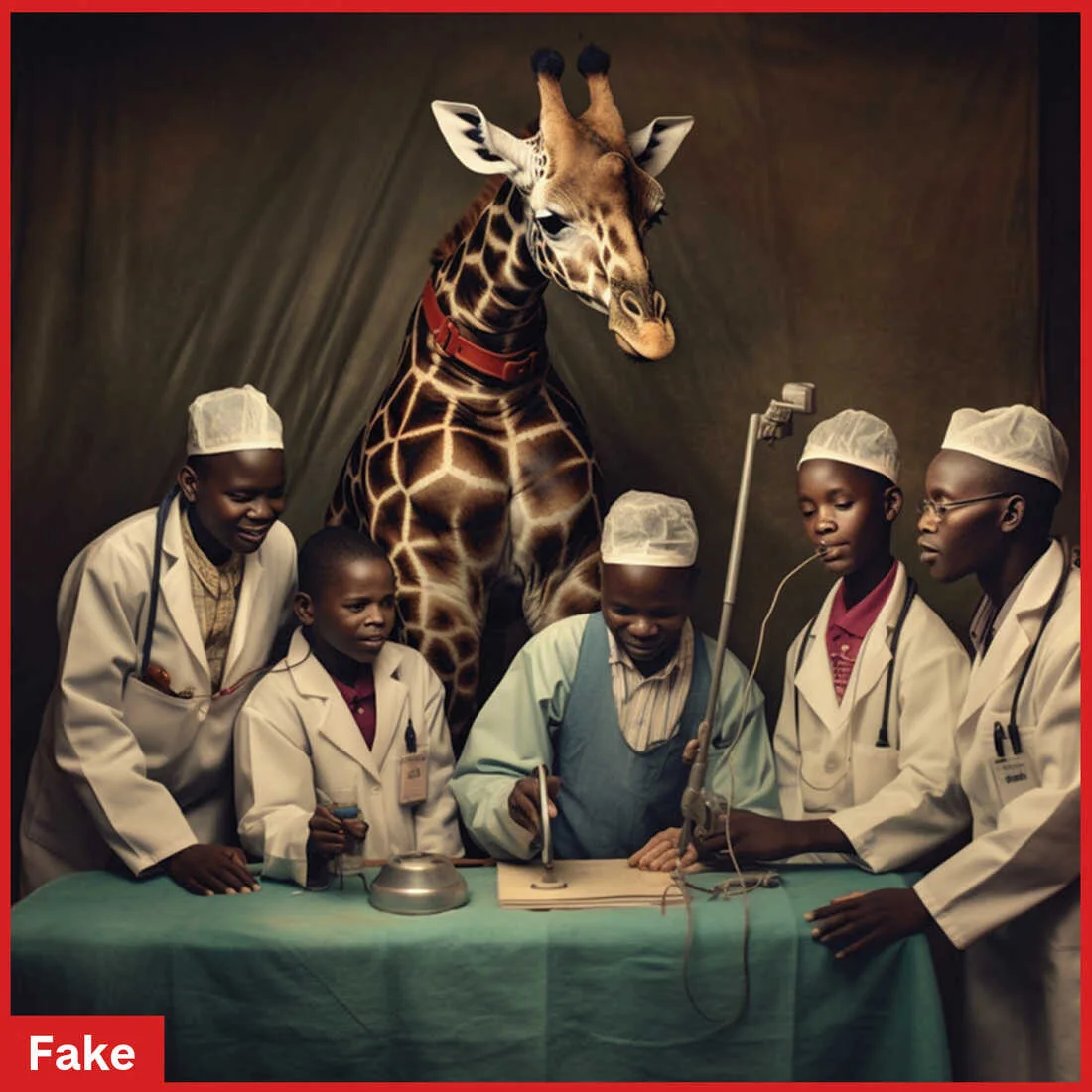

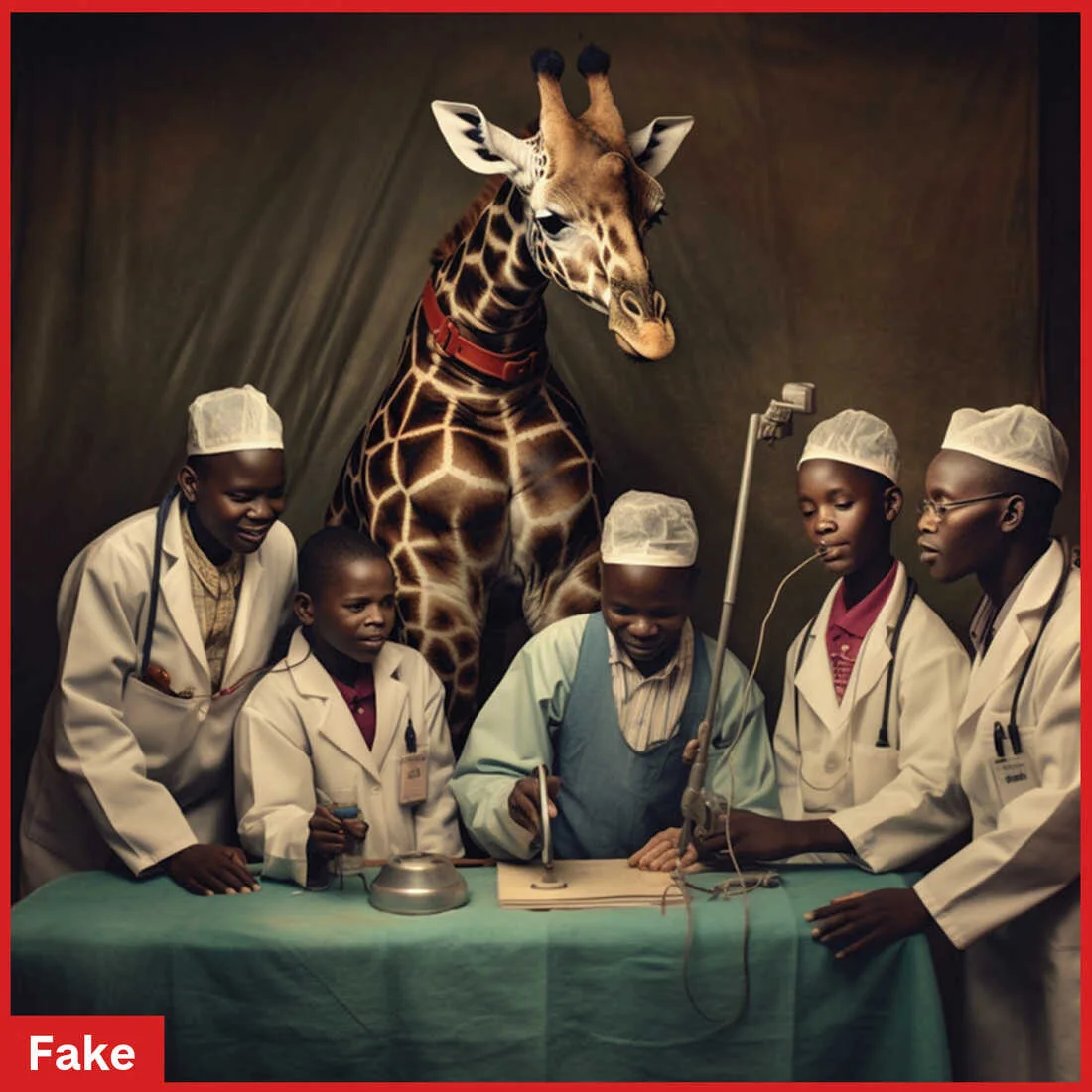

In a request to an artificial intelligence program for images of “doctors help children in Africa, some results put African wildlife like giraffes and elephants next to Black physicians.

Midjourney Bot Version 5.1. Annotation by NPR.

Midjourney Bot Version 5.1. Annotation by NPR.

Try as they might, the team was unable to get Black doctors and white patients in one image. Out of 150 images of HIV patients, 148 were Black and two were white. Some results put African wildlife like giraffes and elephants next to Black physicians.

They also made multiple requests for traditional African healers helping white kids. Out of 152 results, 25 depicted white men wearing beads and clothing with bold prints using colors commonly found in African flags.

And one image featured a Black African healer holding the hands of a shirtless white child who wore multiple beaded necklaces — a caricatured version of African dress, Alenichev says.

The above image is the only one from the experiment that showed a Black figure tending to a white child. This image was generated by a request for traditional African healers helping white kids.

Midjourney Bot Version 5.1. Annotation by NPR.

Midjourney Bot Version 5.1. Annotation by NPR.

The team’s essay about the work appeared in Lancet Global Health in August. “You didn’t get any sense of modernity in Africa” in the images, Kingori says. “It’s all harking back to a time that, well, it never existed, but it’s a time that exists in the imagination of people that have very negative ideas about Africa.”

Consider the source

Midjourney itself has not commented on the experiment. The company did not respond to NPR’s request to explain how the images were generated.

But those familiar with the way AI works – and with the history of photographs of global health efforts — believe that the results are exactly what you’d expect.

Generally, AI programs that create images from a text prompt will draw from a massive database of existing photos and images that people have described with keywords. The results it produces are, in effect, remixes of existing content. And there’s a long history of photos that depict suffering people of color and white Western health and aid workers.

Uganda entrepreneur Teddy Ruge says that the idea of the “white savior” is a remnant of colonialism, a time when the Global North put forth the idea of “white expertise over the savages.” Ruge, who goes by TMS on his website, has partnered with Global Health Corps and other organizations.

To compensate for decades of “white savior” imagery, Ruge says, Africans and people from the Global South “have to contribute largely to changing the databases and overwhelming the databases, so that we are also visible.”

Even before AI, groups have been targeting the issue of images depicting “white saviors.” Radi-Aid, a project of the Norwegian Students’ and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH), fights stereotypes in aid and development, as does an Instagram parody account called Barbie Savior.

Both groups critique “simplified and unnuanced photos playing on the white-savior complex, portraying Africa as a country, the faces of white Westerners among a myriad of poor African children, without giving any context at all,” says Beathe Øgård, president of SAIH.

And the kind of image that Øgård mentions is rampant. A study published in Lancet Global Health in January demonstrated that roughly 1,000 photos from the World Bank and other organizations perpetuated biases by using images of African people out of context or featuring vulnerable-looking Black children. The photos date back to 2015. In response, the journal’s editors announced in February that they would develop new image guidelines for all Lancet journals. “Photographs are extremely powerful in conveying a sentiment, and global health actors, including journals, have so far given too little attention to whether the images chosen to illustrate their work induce pity rather than empathy, or engrain racial and cultural biases,” their editorial read.

Training the computer

Is it possible to defy the biases baked into AI?

Malik Afegbua, a Nigerian filmmaker, artist and producer on the Netflix show Made by Design, wanted to see if he could use AI to generate photos that challenge stereotypes of older people.

His dream: depictions of debonair African elders on fashion runways.

Working with Midjourney, as Alenichev had, he put in phrases like “elegant African man on the runway” and “fashionable looking Nigerian man wearing African prints.”

“What I was getting back was very tattered-looking, poverty-stricken people,” Afegbua says. So he wondered: Could he manipulate AI to deliver what he wanted?

Midjourney’s online guide does say that users can feed it images “to influence the style and content of the finished result.”

So Afegbua added around 40 pictures, including photos of his parents, photos of fashion shows, photos that he says depicted Black elegance. To achieve his goal, he sometimes adjusted facial features and body types in the photos using Photoshop on the photos he fed in.

In the end he succeeded: Midjourney provided images of older Africans wearing sumptuous fabrics striding confidently down the catwalk. Pictured below is one of the images that met his requirements.

Afegbua says he cannot upend all the stereotypes in AI by himself. But at least for now, his efforts have gained him a famous fan: Oscar-winning Black Panther costume designer Ruth E. Carter. “Who created this?,” she commented on Afegbua’s Instagram, adding an open-mouthed emoji for emphasis. “Dope.”

AI images are already out there. So now what?

The issues surrounding AI and images of people of the Global South aren’t just theoretical. Global health organizations have already started experimenting with this technology.

A case in point is an image shared on Twitter, now X, by the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. It portrays a Black child in dirty clothing, standing alone in a plowed field, with the phrase “When you smoke, I starve.”

Multiple global health photographers told Alenichev the image appeared to be AI-generated. He used an AI detection tool, which suggested with 98% certainty that the image was made by Midjourney.

Make that 100%. A WHO spokesperson confirmed in an emailed statement to NPR that the image was made with Midjourney, as were companion images depicting children of various ethnicities next to smoldering cigarettes. “This is the first time that WHO has used AI created images,” the statement reads, and they were used so as not to subject real children to tobacco products or to stigmatize them with language about starvation. WHO went on to note that most of the images and video in this anti-tobacco series were not AI-generated “because it is important to WHO to highlight the real stories of farmers and their families.” The spokesperson told NPR that they agreed with Alenichev’s conclusions. “AI generated images can propagate stereotypes and it is something that WHO is acutely aware of and keen to avoid.”

As for Alenichev, he hopes that his essay establishes that AI is not just a computer program without any biases — and that the global health community needs to have conversations about whose responsibility it is to challenge biased images and who should be held accountable when AI generates them. For all its power, AI “still stumbles,” he says. “We should resist understanding AI as something neutral and apolitical, because it’s not.” He’s now applying for a grant to further examine the issue of biases in artificial intelligence.

Carmen Drahl (@carmendrahl) is a freelance science writer and editor based in Washington, D.C.