Amid celebrations after Gov. Gavin Newsom enacted a slew of legislation as part of the nation’s first statewide reparations package, some Black leaders in San Diego say it is only the start of repairing the wrongs done to Black descendants of enslaved people, and of recommitting to reparative justice.

The half-dozen bills Newsom signed last month are part of California’s multi-year plan to make amends for its past wrongs — and include a key measure that requires the state to apologize for perpetuating slavery and its past “human rights violations and crimes.”

Officials from the California Legislative Black Caucus say the package is not just a victory for California but also a defining moment in a nationwide movement for reparative justice.

But lawmakers stopped short of enacting some of the more substantial bills, local Black leaders and community advocates point out.

The Black Caucus had advanced 14 priority bills in January with far-reaching goals. Six were ultimately signed into law; seven others either failed or were vetoed. The final proposal, Proposition 6, will be decided by voters.

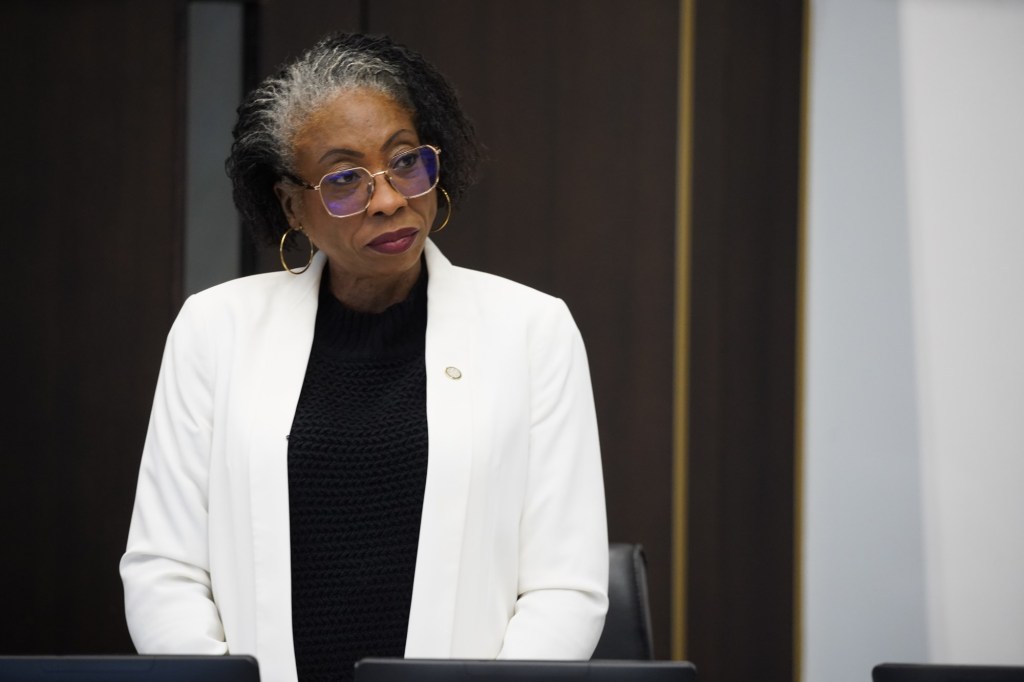

Monica Montgomery Steppe, now San Diego County’s first Black woman supervisor, was on the state’s reparations task force, a nine-member group group led with researching and developing recommendations to the state.

She told The San Diego Union-Tribune she has mixed feelings.

“I am very grateful that we are more openly talking about reparations and what that means for descendants of enslaved people — and that is progress,” she said. “At the same time, there were bills that I thought should have been voted on and or signed by the governor that were not.”

Calling the package the start of repairing the wrongs, Montgomery Steppe said she’s grateful for the progress but disappointed that more of her panel’s recommendations weren’t implemented.

“There’s a whole lot more work to do, don’t get me wrong — but this is a step in the right direction,” said Ellen Nash, who chairs both the San Diego chapter of the Black American Policy Association and the county’s Human Relations Commission.

Other parts of the reparations package that became law address issues the task force identified as having long disproportionately impacted Black Californians, such as housing disparities, maternal health, economic inequality and educational access.

“The State of California accepts responsibility for the role we played in promoting, facilitating and permitting the institution of slavery, as well as its enduring legacy of persistent racial disparities,” Newsom said in a statement. “Building on decades of work, California is now taking another important step forward in recognizing the grave injustices of the past — and making amends for the harms caused.”

California joins seven other states in issuing a formal apology. But its reparations package is the first of its kind, a milestone in a nationwide effort and a blueprint for other states, Black Caucus officials said.

The state’s reparations task force issued last year a 1,000-page document with more than 200 recommendations following two years of public hearings, culminating in the 14-bill package.

But with only half of that package moving forward, Black legislators say there is more to be done.

One bill that failed would have funded solutions to reduce violence in Black communities by establishing a state-funded grant program. Another would have restored property taken during race-based uses of eminent domain to its original owners. And a third would have made food and nutrition intervention a permanent part of Medi-Cal benefits.

Newsom only vetoed two of those policies, the eminent domain and Medi-Cal benefit ones. The rest did not make it through the Legislature.

In his veto message, Newsom said he vetoed the eminent domain bill because the state agency that would carry out its provisions doesn’t exist. He cited a budget deficit for the Medi-Cal benefit veto and encouraged the Legislature to present the policy next year as a part of the annual budget process.

Montgomery Steppe said she’s disappointed in his decision and both pieces of legislation would have been “very fruitful for the community and the beginning of that tangible work.”

Two of the package’s most substantial bills were blocked in the final hours of the legislative session last month, including the one that would have created a fund for future reparations payments.

The other was Senate Bill 1403, which would have established the California American Freedmen Affairs Agency to help implement the reparations package and a genealogy unit within it that would have established standards for proving eligibility.

Montgomery Steppe was most disappointed to see that policy fail, calling it “foundational in the work of reparations in California.”

Members of the Black Caucus say they remain committed to trying again in the upcoming legislative session.

Meanwhile, Nash says the reparations package has underscored the importance of making sure underserved communities know about the existing reparation programs and resources available to them.

“We really need to educate people and so they are aware of the benefits that already exist that uplift underserved communities like the Black community,” she said.

While she looks forward to the revival of the reparations bills that failed, Montgomery Steppe says she will also look at ways to implement those that were enacted at the local level.

Just this week, she asked her colleagues on the Board of Supervisors to support Proposition 6, which would amend the state constitution to ban involuntary servitude in prisons. It passed 4-0, with Chair Nora Vargas not present.

“I’ve always said that this was going to be a very long fight,” Montgomery Steppe said. “My hope is that it’s not a lifetime fight for me, and that we can get to a point of really providing solutions around reparations to receive true equality in California and nationwide — but if it is a lifetime fight, then I’m certainly in it for the long haul.”