Researcher and scholar Kerby Lynch visited Diablo Valley College on April 4 to discuss reparations for slavery — legislative changes that would seek to repair the economic, societal and psychological damages caused by systemic racism in the 400 years since slavery was introduced to North America.

Lynch, who serves as the director of research at Ceres Policy Research and authored the book The Philosophy of Black Insurgency, said it’s important for the country to address the injustices perpetrated against the descendants of enslaved African Americans, because “for the past 400 years, folks of that experience have been silenced, have been made to feel everyday that they should just move on.”

The idea of reparations is not new, Lynch said, noting that in the 1980s the U.S. issued reparations to Japanese Americans who were corralled into internment camps during World War II.

Other countries, including Australia, Germany and South Africa, have also implemented reparations for institutionalized human rights violations. But the U.S. government has been slow to address reparations for slavery, she said.

“We’ve had multiple movements—Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Movement—however, it seems as if the message is not coming home,” Lynch said.

African American author Ta-Nehisi Coates reinvigorated the national discourse on reparations in 2014 with the publication of “The Case for Reparations,” an essay that pressed the U.S. government to atone for its complicity in institutional racism against African Americans.

In 2019 Coates, along with civil rights activists and economists, gave testimony at a congressional hearing on H.R. 40, a bill introduced to Congress every year since 1989 that proposes to establish a federal slavery reparations commission.

The bill has stagnated in Congress, but in September 2020 the state of California established its own reparations task force, where Lynch worked as a researcher.

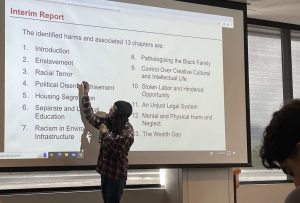

In January of this year, the California Legislative Black Caucus introduced a repartions package of 14 bills based on the task force’s recommendations report.

The state’s reparations package does not include cash payouts, which have proved contentious, as some reparations supporters advocate direct financial assistance while others argue that lineage-based eligibility would leave out individuals who lack access to family records of enslaved ancestors. One of the recently introduced reparations bills intends to establish an agency that would assist Black Californians in researching their lineage.

The proposal for cash reparations has received pushback from members of Congress and the public, as only 30 percent of U.S. adults support direct compensation, according to a 2021 Pew survey of 6,500 U.S. adults.

But Lynch said reparations, in their various forms, are crucial to rectify the legacy of slavery and systemic racism.

“An act of confrontation”

Reparations would not only seek to repair the political and economic injustices that exist today, Lynch said, but would also require a reckoning with the history of systemic oppression against Black Americans.

Lynch said the U.S. still operates by the racial formation theory, which she said describes race as “the central social institution that undergirds our everyday life.”

She said she was “really, really shocked… that in the San Francisco Black community a lot of people just don’t know the extent of how much racism has impacted their quality of life and their life expectancy.”

For example, Lynch noted that Black communities have particularly high rates of potential life loss, calculated in comparison to the average national life expectancy of 75.

According to a study published in the National Institutes of Health, Black communities experienced 1.63 million more deaths than white populations from 1999 to 2020.

“Race, and how we understand a person to be racialized, is actually what’s going to determine their experience in certain social institutions, economic institutions, and political spheres,” Lynch said.

Lynch recounted that as a 19-year-old UC Berkeley undergraduate student pursuing her B.A. in African American Studies, she and her friends were accosted by police officers for jaywalking in Berkeley.

The incident took place in May 2014, she said, four months before the police killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., which sparked the first massive wave of protests in the Black Lives Matter Movement.

Lynch explained that when the media is flooded with images of police brutality, it normalizes the brutalization of Black people and generates an acceptance of racial hegemony.

“We’re falling into the acceptance that we normalize the brutality that we’re seeing against Black people,” Lynch said.

“We’re normalizing the fact that we had a system of brutal slavery against African Americans in this country. When we normalize those things, we are also naturally coming into the acceptance of domination.”

Therefore, she said, it’s important to approach reparations as “an act of confrontation” with the entire history of American imperialism and the various societal and economic systems that have perpetuated racism against Black Americans.

The reparations movement has generated considerable opposition from various sectors of the population, as opponents argue that people alive today are not responsible for the enslavement or injustices that occurred hundreds of years ago.

The recent surge in book bans across the U.S. and curriculum censorship targeting critical race theory has shown that many Americans remain unwilling to confront America’s ugly history of racism.

But Lynch said such confrontation is necessary for the nation to move forward.

“Our country actually cannot heal, our country can actually not come to a consensus until we have some real conversations about the foundation of this country, about the profits of plantation slavery and how it is the economic foundation of this country,” she said.

“Economics as a practice of racism”

In her talk, Lynch explained that unpaid slave labor served as the foundation of the American economy, enabling the U.S. to emerge as a global superpower after World War I.

Comparing the U.S. economy to a corporation, Lynch said, “If you just think about it, we had a huge labor force that we didn’t pay wages to for about 300 years and used all of that excess capital to reinvest into [our] own corporation.”

Lynch said the modern American economy has perpetuated economic injustices against African Americans through discriminatory practices such as redlining, predatory lending, and debt slavery.

“The economy in this country is 100 percent rooted in racial configurations of hierarchy,” Lynch said.

“The systems that exist today, they’re not really broken, they were built that way. So for those of us who have been impacted by these systems for generations and generations, reparations is our policy movement to radically transform these systems.”

Although California’s reparations bills strive to rectify the economic effects of systemic racism, the absence of direct monetary assistance among the provisions has stirred up a “huge controversy,” according to Lynch.

Lynch expressed her support for direct financial assistance, but she also noted that the California Reparations Task Force intended reparations to be more comprehensive than just simply cash payments.

“Reparations isn’t just about the 40 acres and a lamborghini that we’ll receive,” she said, referring to the unfulfilled promise of Field Order No. 15, a Reconstruction-era program that would have granted formerly enslaved African American families “40 acres and a mule,” had it not been struck down by President Andrew Jackson.

“It’s not just about the cash,” she added. “It’s about transforming the society.”

Different types of reparations

Lynch emphasized the importance of learning about different types of reparations, as outlined in Marcus Anthony Hunter’s recently published book, Radical Reparations: Healing the Soul of a Nation.

For example, she said, political reparations would call for better representation of African Americans in the government.

“We know that the federal government, by and large, is about 76 percent white and male, which isn’t even representative of this room,” Lynch said, gesturing to the audience.

Similarly, legal reparations would address racial disparities in funding across different government departments, such as public housing.

Intellectual reparations, meanwhile, would recognize and compensate for the theft of Black intellectual property, which had obstructed the opportunities for Black individuals to build generational wealth.

Along a similar vein, she said, spatial reparations would aim to return private property confiscated through the discriminatory practice of eminent domain, and construct affordable housing in Black communities that were affected by urban renewal in the 1960s.

Additionally, spiritual reparations would constitute a formal recognition of the horrors of slavery and the cultural loss experienced by enslaved African Americans and their descendants.

Finally, Lynch said, social reparations would seek to dismantle racial prejudice at its core.

“Reparations as a movement is a political movement, but it’s also a spiritual movement to say ‘I am not inferior,’” she said.

Lynch designated this reckoning as “the main thing that would provide healing and true justice for folks who are impacted by this experience to really move forward.”