In October, President Biden issued a formal apology on behalf of the U.S. government for the historical kidnapping, relocation, and abuse of thousands of Indigenous children placed in so-called “boarding schools” between 1819 and 1969. The American Indian Boarding Schools program, which included the residential schools in Canada, Australia, and other settler colonies, was part of a broader campaign aimed at facilitating the genocide of Indigenous communities. This apology marked Biden’s first visit to Indian Country since taking office. Given its proximity to the 2024 federal election, this gesture has ignited ongoing debates not just about its sincerity, but material impact on the well-being of Indigenous communities in the so-called United States. Issued amid the looming threat of transition from the Biden-Harris administration to the (then-potential) Trump-Vance administration, many have questioned whether this apology was more about political optics than the state’s commitment to accountability, reparations, and real, lasting change for Indigenous communities.

This is far from the first time a U.S. president has issued an apology without meaningful action to follow. In the 1990s, President Bill Clinton apologized for the role of the United States in the transatlantic slave trade during a visit to Africa. But despite this apology, Clinton maintained that he did not support reparations in the form of cash payments to the descendants of enslaved people, with a CNN report of the moment documenting Clinton’s belief that “the nation is so many generations removed from that era that reparations for Black Americans may not be possible.” Much like Biden’s apology, Clinton’s gesture was framed as a long overdue step toward reconciliation. However, the limitations of formal acknowledgments in confronting white supremacy and settler colonialism have never been more evident.

Today, Indigenous children are disproportionately represented in the child welfare system, often referred to by organizers, legal advocates, and scholar-activists as the “family policing system.” Rather than placing stolen Indigenous children into the so-called “boarding schools” of the past, child welfare workers continue to facilitate state-sanctioned family separations by removing Indigenous children and relocating them into the foster care system. Recent attacks on the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), a federal law establishing the minimum standards for when Indigenous children can be removed as well as a preference for placing Indigenous children with family and tribal members, underscores how the machinery of genocide remains intact, albeit modernized. In Haaland v. Brackeen, an anti-ICWA lawsuit brought by several plaintiffs, including the State of Texas and Dr. Jennifer and Chad Brackeen—a white evangelical couple from Fort Worth—challenged the law after their petition to adopt a Navajo-Cherokee boy they had been fostering was denied. The fact that non-Indigenous families like the Brackeens feel so entitled to Indigenous children that they would demand they be permanently severed from their familial and tribal identities reveals the deep-seated nature of settler colonialism embedded in the family policing system.

Shawna Bullen-Fairbanks, an Indigenous woman who entered foster care at eight years old, reflected:

“Foster care is generational in many Native American communities. It started with the residential Indian boarding schools. Since then, we have been overrepresented in the foster care system nationwide…this is another form of genocide. It’s known as ‘cultural genocide,’ and I’ve experienced it in foster care…I forgot how to dance in powwows, as well as other traditions, teachings, and stories… I was really close to my maternal grandmother growing up, and when I went into foster care, I lost that relationship due to being distanced in a group home. For my so-called ‘safety,’ the group home refrained for two weeks from telling me that my grandmother had died and thus prevented me from going to her funeral. I felt so heavy in my heart because I learned most of my culture as a child from my grandma. I was hoping when I left foster care, I could turn to her for guidance, but I lost her instead.”

In recent years, the conversation around reparations has gained significant momentum, with formalized local, state, and national efforts emerging to study the legacy of chattel slavery and other forms of state-sanctioned violence and make recommendations for redress. However, there is growing concern that as the state becomes more and more involved in the historical question of reparations, the concept itself is being co-opted and reduced to symbolic gestures, like apologies and one-time financial payments that fail to meaningfully alter the conditions that produced the violence at the center of the conversation. And, in many modern cases, the state-sanctioned violence for which government officials and programs seek to apologize continues completely unabated.

What is an apology from the President of the United States worth if genocide persists? What exactly is so progressive about liberal leadership if reparations do not include cessation of settler colonial violence, and why has our demand failed to make it clear that we are unwilling to accept less?

The question at the heart of Los Colonos is a confounding one: given all that has transpired to build the nation-states we today inhabit—and the world system they comprise—what now?

A Case Study in “Repair” Under Liberal Leadership: Reproductive Violence in California

A striking example of this disconnect between liberal leadership’s reconciliation efforts and the reality of material conditions can be found in the bright blue state of California.

In 1909, California became the third U.S. state to enact a sterilization law, establishing a state-run sterilization program. By the time the law was repealed in 1979, over 20,000 people had been involuntarily sterilized—approximately one-third of all state-sponsored sterilizations in the U.S. during this period.

In 2003, then-California Governor Gray Davis issued a formal apology to survivors of these sterilizations, calling it a “sad and regrettable chapter” in the state’s history and expressing deep regret for the suffering caused by the state’s eugenics-era policies.

However, despite Davis’ apology, the material consequences of this violence—reproductive trauma, loss of autonomy, and the ongoing legacy of racialized reproductive violence within California’s legal and healthcare systems—were left largely unaddressed.

Though the state’s sterilization law was repealed in 1979, state-sanctioned reproductive coercion persists. In 2013, investigative reporting revealed that at least 148 involuntary sterilizations had occurred in California’s prisons between 2006 and 2010—long after the state’s sterilization law had been repealed. These sterilizations were done covertly, with little to no records kept (if there was ever documentation at all), ensuring that those responsible remained unaccountable.

In response to years of grassroots pressure, investigative journalism, and advocacy from groups like California Latinas for Reproductive Justice (CLRJ) and the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP), the California State Senate passed SB 1190 in 2018, creating a reparations program to compensate survivors of involuntary sterilization. However, the program’s eligibility requirements are narrow, leaving many survivors excluded—such as those sterilized at the Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center, where over 200 people, mostly women of Mexican descent, were coerced into sterilization procedures. Furthermore, the compensation program has struggled to process claims: by the end of 2023, only 51 of over 300 applicants had been approved, and many survivors were denied due to bureaucratic red tape and destroyed (or nonexistent) state records. Survivors accepted into the program received a total of $35,000, not considered taxable.

In what can only be described as a final indignity, the state of California signed a $280,000 contract with JP Marketing in 2023 to launch a social media and TV/radio advertising campaign to reach eligible survivors. This move was likely an attempt to manage public perception—further substantiated by the not-so-quiet rumor that California Governor Gavin Newsom is likely to make a bid for the presidency in 2028. The state’s emphasis on media strategy forces the question: why is there money for marketing but not for ensuring that all eligible survivors receive the bare minimum—a formal apology and compensation?

The case of Geynna Buffington, a survivor who only discovered she had been sterilized when she was unable to conceive after her incarceration, further underscores the failures of the state’s reparations efforts. Buffington’s claim was initially rejected four times by the California Victim Compensation Board (CalVCB), which argued that she hadn’t been sterilized—despite clear evidence that her procedure, an “endometrial ablation,” is a form of sterilization. The matter was eventually resolved by the Alameda County Superior Court, which ruled that Buffington had been wrongfully denied reparations. Newsom later signed a law allowing other survivors whose claims had been denied to appeal CalVCB’s decision until January 1, 2025.

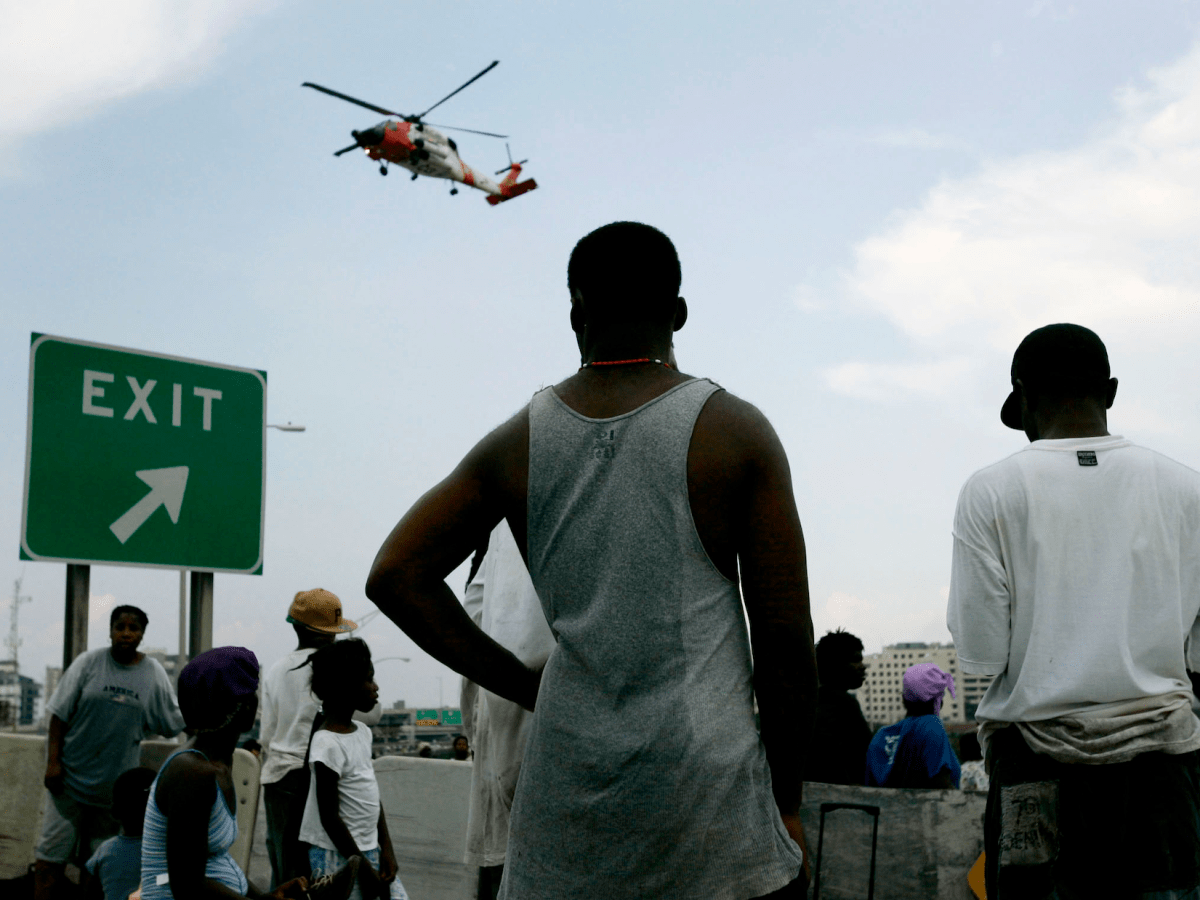

New Orleans native and storm survivor Cierra Chenier reflects on how state abandonment and exploitation after Hurricane Katrina provided a new blueprint for neoliberal crisis mismanagement—evident in the insufficient response to the Maui wildfires.

The Limits of Symbolic Justice

California’s reparations program for survivors of forced sterilization, like the handful of similar so-called reparations programs across the United States, reveal a disturbing trend: apologies and minimal financial compensation are inadequate redress for the systemic violence that continues to harm Black, Indigenous, and other racialized communities in the United States. These programs, by design, fail to confront the root causes of state-sanctioned violence—white supremacy, ableism, and settler colonialism—and even when survivors do receive compensation, it is often in token amounts that are swallowed up by bureaucracy, record-keeping failures, and legal loopholes that allow the violence to persist. For example, California remains one of 31 states, according to the National Women’s Law Center, where the sterilization of people with disabilities is still legal in certain circumstances, and it is well-known that U.S. jails and prisons are sites of reproductive and sexual violence for incarcerated people.

Even in much more optimistic cases, such as the survivor-led fight for reparations for victims and survivors of police torture under Jon Burge and the Chicago Police Department, which (in addition to a formal apology and compensation) included the creation of the Chicago Torture Justice Center, priority access to city employment for torture survivors, free enrollment in city colleges for torture survivors and their families, and several other initiatives—these steps cannot be called “repair” as long as the systemic violence continues. The Chicago Police Department remains a force of terror for the people of Chicago, and more survivors of state-sanctioned torture are created every single day. The city of Chicago has also been slow to see this reparations package through, with survivors’ work now focused on pressuring the city to fund a memorial in their honor, which was promised to them by the city itself. What has been repaired when systems of abuse and carcerality remain intact and, in many cases, will expand through “Cop Cities”?

These ongoing practices of control, erasure, and harm make clear that the U.S. has never fully confronted the deep structural violence embedded within its legal, healthcare, and political systems. Reparations limited to symbolic gestures, financial payments, or apologies—without dismantling the structural systems that perpetuate these harms—or that the State can stall, as is the case in Chicago, will never be justice. Until we confront the continuing violence of settler colonialism, white supremacy, ableism, and other intersecting forms of oppression that underpin these practices, reparations will remain hollow and insufficient.

The Urgency of Reimagining Demands for Reparations from a Decolonial Perspective:

The limitations of what has been accepted as reparations and reparative justice become even more urgent to address when considering the colonial status of Puerto Rico. Recent remarks at a Trump rally, where Puerto Rico was referred to as “a floating island of garbage,” sparked widespread outrage. However, the defense of Puerto Rico by figures like former President Barack Obama—who claimed, “they’re Americans”—fails to recognize an uncomfortable truth: Puerto Rican citizenship was not freely chosen, but rather imposed. In 1917, after the U.S. colonial takeover of Puerto Rico in 1898, the U.S. unilaterally imposed U.S. citizenship on Puerto Ricans, in anticipation of U.S. involvement in World War I, making it a stark example of how citizenship has historically been wielded as a tool of colonial control, rather than a gesture of reconciliation. This citizenship, which many liberals view as a precursor to full statehood, is also a means of denying the genocide and erasure of Indigenous and Black Puerto Ricans. The framing of statehood as reconciliation, rather than sovereign self-determination, further reinforces the colonial nature of U.S. governance over the island and how Puerto Rican support for independence is conveniently ignored in mainstream discourses.

Despite being U.S. citizens, Puerto Ricans on the island remain subject to colonial governance, where their rights and autonomy are subordinated to the interests of the U.S. mainland, most often exemplified by the instability of the island’s electric grid. The island’s status as a U.S. territory continues to facilitate the extraction of its resources while denying Puerto Ricans true political representation and self-determination. This lack of self-determination, both for Puerto Ricans on the island and in the diaspora, exposes the hypocrisy of framing citizenship as a form of “reconciliation.” The ongoing exploitation of Puerto Rico’s land and people shows that symbolic gestures—whether through apologies or citizenship—are too often used as tools of genocide denial and erasure, rather than genuine steps toward justice.

As only the second generation of my family to be born on the U.S. mainland, I continue to feel the visible consequences of Puerto Rico’s colonial legacy, especially through language. While Spanish is, of course, also a colonial language, I do not speak it, and this lack of fluency means that I will likely never be able to conduct the research on the island necessary to reconnect with my Afro-Indigenous roots. My grandmother, who taught my mother that “English is the way,” did not do so out of shame, but out of necessity. Puerto Rico is nothing more than an investment for U.S. capital, and in my abuela’s mind, the best chance for safety and survival was to prioritize English and embrace the norms imposed by the mainland. This tragic reality is compounded by the remarks made by the Trump camp and many liberals who, in the wake of electoral defeat, find it easier to scapegoat marginalized groups—Latinxs, Palestinians, Muslims—rather than confront the complicity of the Democratic Party in fostering exploitation and inequality in the U.S., Puerto Rico, and elsewhere. These remarks affirm that, despite our citizenship and the symbolic “gift” of inclusion, we remain dirt beneath the shoe of a rapidly declining empire.

Conclusion

If we are serious about reparations and reparative justice, the concessions we demand and accept from the settler colonial state must be more than hollow apologies and financial transactions. Repair cannot be reduced to symbolic gestures; we must be clear that repair requires a total end to the settler colonial entities under which Indigenous, Black, and other racialized communities suffer. Reparations will never mean justice unless and until it is synonymous with an explicit and collective demand for an end to the systems built upon our blood and suffering. Until we organize toward that end, every gesture—whether a presidential apology, a one-time payment, or a public art installation—will remain meaningless. Repair is only possible when the violence stops. Until then, Black, Indigenous, and other people of color—on the mainland, in Puerto Rico, and the rest of the lands under U.S. hegemonic domination—will continue to bear the weight of a nation that refuses to confront the truth: the U.S. does not only have a colonial and white supremacist past—it has a colonial and white supremacist present. The question is whether we will allow that present to remain our future, or if we have had enough.