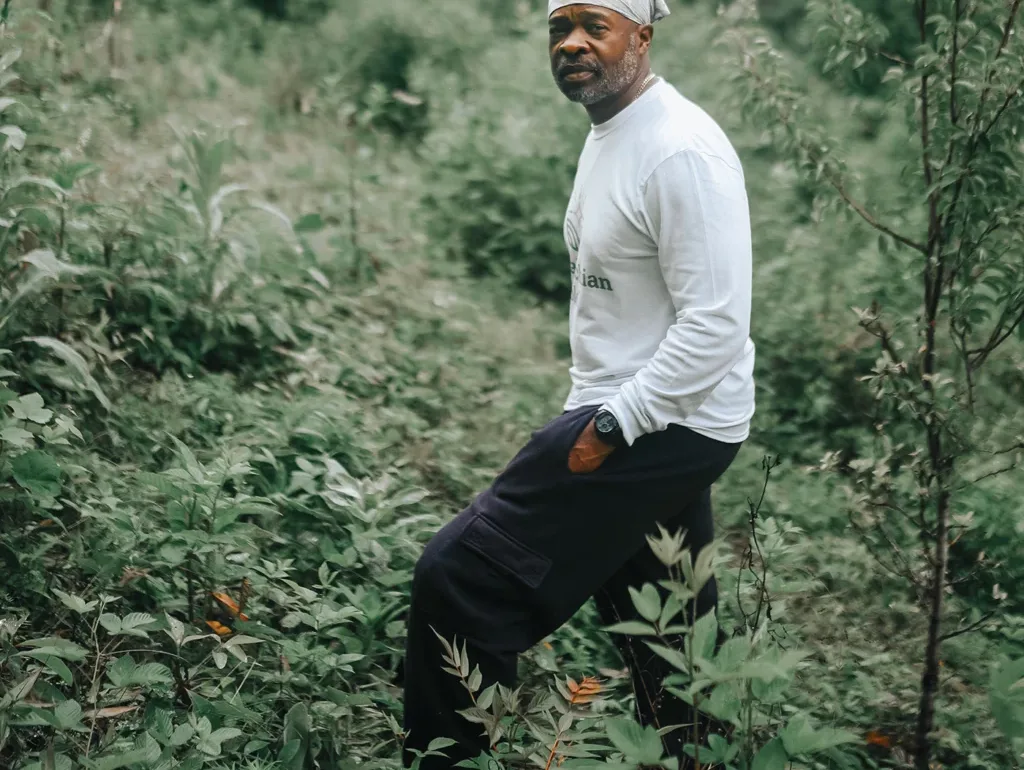

Jason Tartt’s farm is an oasis in the making. Apple orchards, maple and peach trees, apiaries for cultivating honey, and raspberry and blackberry bushes line his 335-acre property in Vallscreek, West Virginia. But beyond the beauty and sustenance Tartt is cultivating in the rolling hills of unincorporated McDowell County, he’s also tapping into his own history—returning to the land and reaching back to his roots.

“My people migrated here in the early 1900s, when the coal mining boom really started to happen,” Tartt says. “The pay was better, the racism wasn’t as bad. It was bad, but not as bad. … Black people were very instrumental in building the framework for the coal mining industry here in West Virginia.”

To a casual observer, this southern West Virginia county is devastated, disregarded, and depressed—a manifestation of the federal government’s “War on Poverty.” Now, nearly 60 years after that federal effort officially launched with these hills in mind, McDowell County is ripe for revival.

Tartt sees boundless opportunity for inclusive growth and shared prosperity through sustainable farming practices designed to build a thriving community. A military veteran who returned to McDowell County in 2010 due to familial obligations, Tartt co-founded the farming cooperative McDowell County Farms with the late Sylvester “Sky” Edwards in 2014. Two years later, the nonprofit Economic Development Greater East (EDGE) evolved out of a working group Tartt co-led. EDGE now provides training in agricultural entrepreneurship, sustainable local farming techniques, and more through its Thrive program, offering locals opportunities to learn new skills.

“Prosperity involves good health, involves [a] clean environment, and involves equity in business and everything that we do. Not everyone can be rich, but you can still live well and have a quality of life,” Tartt says. “So [we’re taking] a holistic approach to whatever we’re doing, to make sure the community benefits and we’re not doing it to the detriment of our environment.”

Prosperity involves good health, involves [a] clean environment, and involves equity in business and everything that we do. Not everyone can be rich, but you can still live well and have a quality of life.”

—Jason Tartt

Gardeners can appreciate the growth of their tomato plants while hoping to limit the spread of the aphids that might eat those plants. Teachers can value growing class participation or attendance rates, but would likely not prefer an increase in class size. Low-wage workers who would benefit from higher incomes probably aren’t as interested in having their debt grow. So growth itself is a value-neutral concept. It’s the context of that growth—and its limitations—that matters.

Who Gets to Grow?

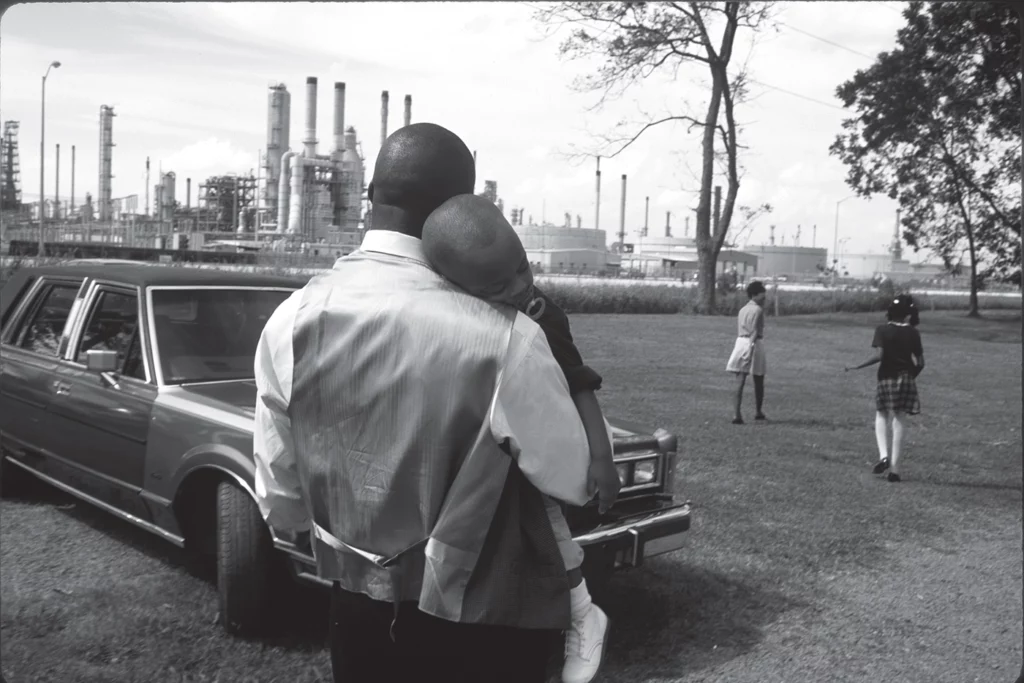

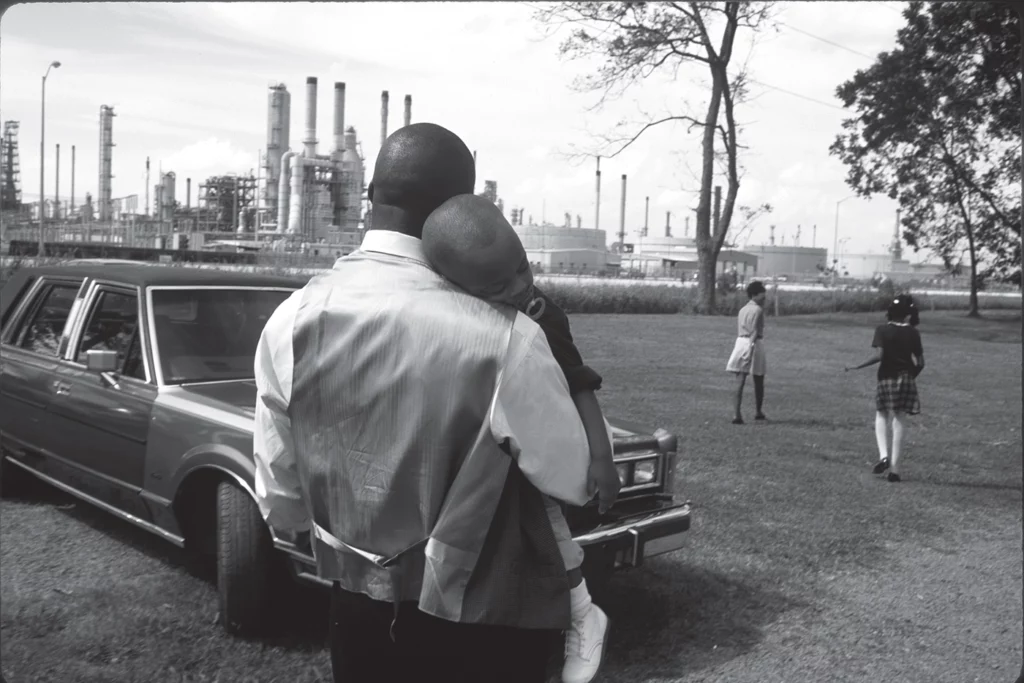

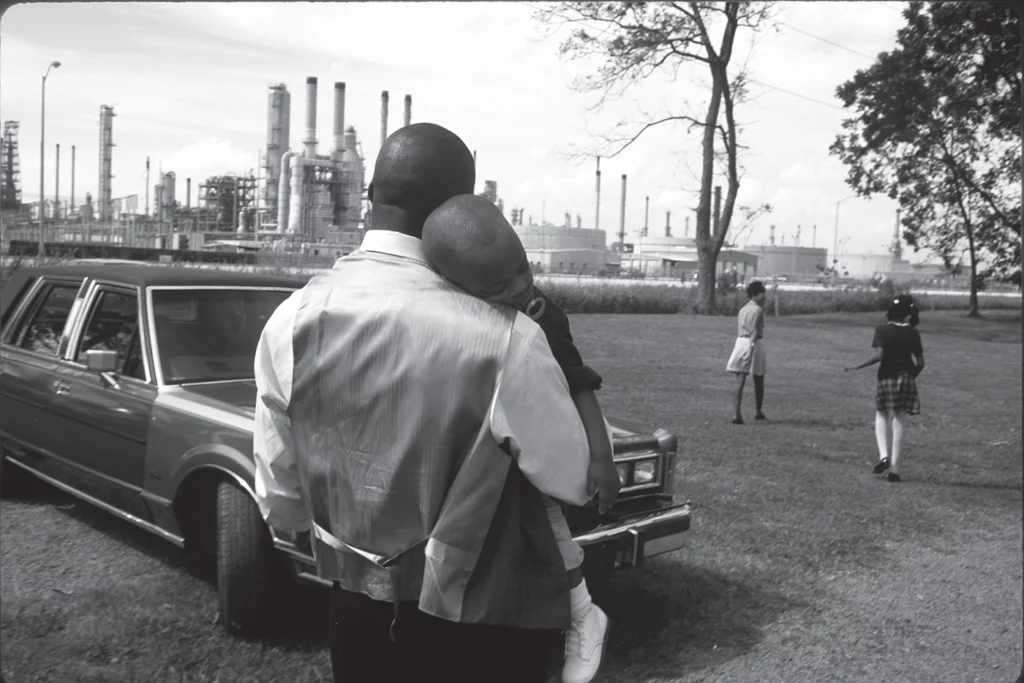

Since the market revolution of the early 1800s made mass production possible, the United States has increasingly adopted a narrative that capitalism requires unfettered economic growth—willfully ignoring the array of harmful outcomes such growth produces. Prioritizing economic growth without constraints has contributed to environmental degradation, from soil-stripping agricultural practices and deforestation to the depletion of clean water. This unyielding adherence to growth threatens public health by allowing polluting industries to contaminate the air and water, which in turn increases the incidence of asthma, heart attacks, and premature death in the predominantly low-income and Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color where these industries are typically housed.

Despite platitudes about “rising tides lifting all boats” or “trickle-down” economics, at no point in this country’s history has economic growth been equitable. As with the rise of the robber barons during the Gilded Age, today’s extreme wealth corresponds with extreme economic inequality. From 1989 to 2018, the wealth of the top 1% increased by $21 trillion, according to Federal Reserve data. During the same period, the wealth of the bottom 50% decreased by $900 billion. Between the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020 and May 2022, the combined wealth of the more than 700 billionaires in the U.S. increased by 58%—to more than $1.7 trillion.

History clearly shows that unfettered growth in the name of capitalistic “success” results in sustained and growing inequality, human and planetary exploitation, and worse. Yet there are other models—many that come from Black, Indigenous, and other historically marginalized communities—that take a more holistic, symbiotic approach to growth.

Consider the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) principle of seven generations, where every decision is made with consideration for the next seven generations to come. The Akan people of Ghana embrace a similar sense of interconnectedness through sankofa, which refers to the value of learning from the past to improve the present and future.

A growing number of organizations around the U.S. and beyond are already reenvisioning growth and prosperity in ways that advance communal needs and planetary stewardship. The Bronx Cooperative Development Initiative (BCDI) is a community-led planning and economic development organization committed to creating an “equitable, sustainable, and democratic local economy that creates shared wealth for low-income people of color.” The BCDI hosts political and business education programming and operates the Bronx Innovation Factory, an advanced manufacturing lab offering tools and training to help local innovators bring their ideas to reality and build wealth in the Bronx.

Organizations like the Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN) center environmental and economic justice in their approach to redefining prosperity. APEN focuses on—and marshals support around—frontline communities most often harmed by pollution, corporate greed, and environmental racism. In addition to policy advocacy and clean energy training, APEN is forming land trusts to support longtime California residents—often immigrants and people of color—to own and remain in their homes in clean, healthy, livable neighborhoods.

Regardless of an organization’s particular focus, collaboration within and across communities is key. By rejecting toxic individualism in favor of collectivism and care, these businesses, organizations, and communities are proving that prosperity can look very different than what has been sold to most Americans as “success.”

The problematic notion that “more is better” predates the establishment of the nation, but the concept has been supercharged during particular moments in U.S. history. By the time the first English settlers arrived in Jamestown in 1607, growth had become intricately linked to prosperity for that population. Settler colonialism relied on territorial expansion—growth centered on claiming, settling, and cultivating an increasing amount of land. And this growth did indeed create prosperity—at least for white people.

By the end of the 19th century, the U.S. was on its way to becoming the wealthiest nation in the world as a direct result of dispossessing Native Americans of more than 1.5 billion acres of land and using enslaved labor to dominate the textile industry. The industrial revolution ushered in a new era of wealth extraction, as robber barons like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller exploited low-wage workers (often immigrants and children) to create their steel, oil, and railroad empires.

In the meantime, “manifest destiny” emerged as the country’s divinely ordained justification for continued settler expansion across the continent. The association between material wealth and the “American Dream” only grew during this period of stunning wealth inequality. Consumption as an indicator of prosperity solidified further during the Roaring ’20s, with the widespread adoption of cars, telephones, radios, and household appliances. Consumer credit also became more readily available, encouraging people to buy now and pay later. The mantra of “More!” was no longer only the province of elites.

By the time Herbert Hoover coined the term “rugged individualism” in a 1928 campaign speech, the concept of individualism was firmly ingrained in the nation’s dominant culture. This narrative emphasizes personal achievement, disregarding values of cooperation, mutual support, and community. It also invisibilizes the array of public support—from public roads and the postal system to tax breaks—that businesses rely on, not to mention the racial, gender, educational, and socioeconomic advantages that their founders often enjoy.

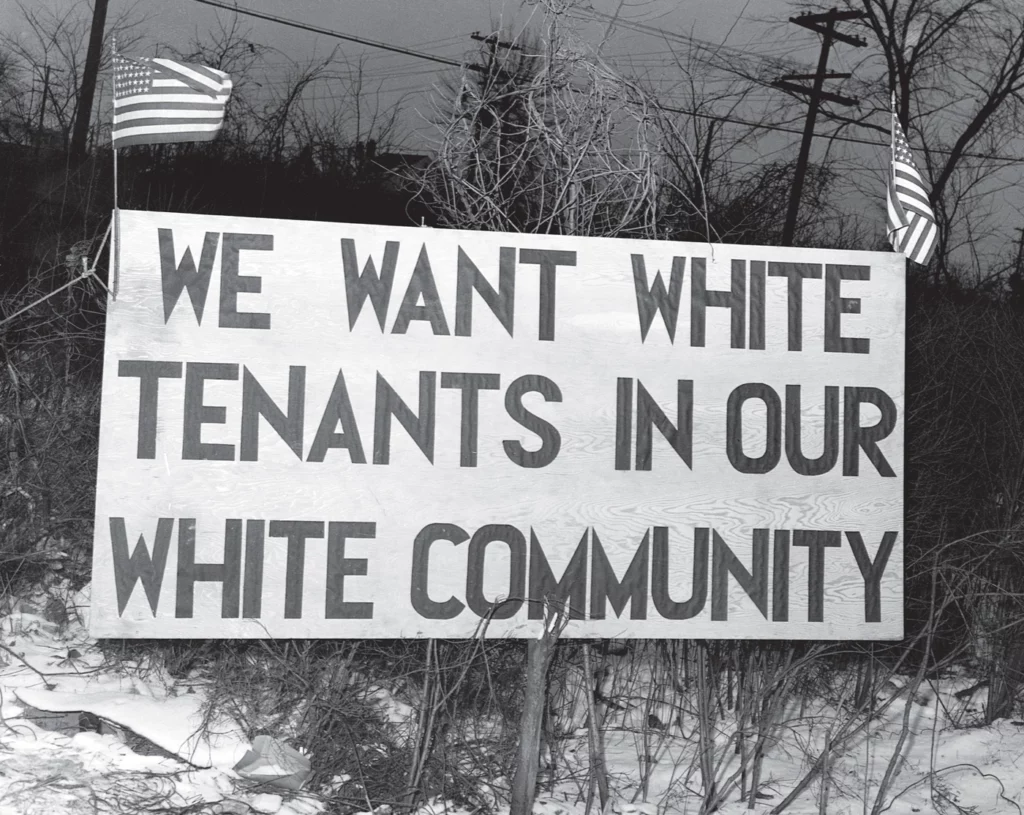

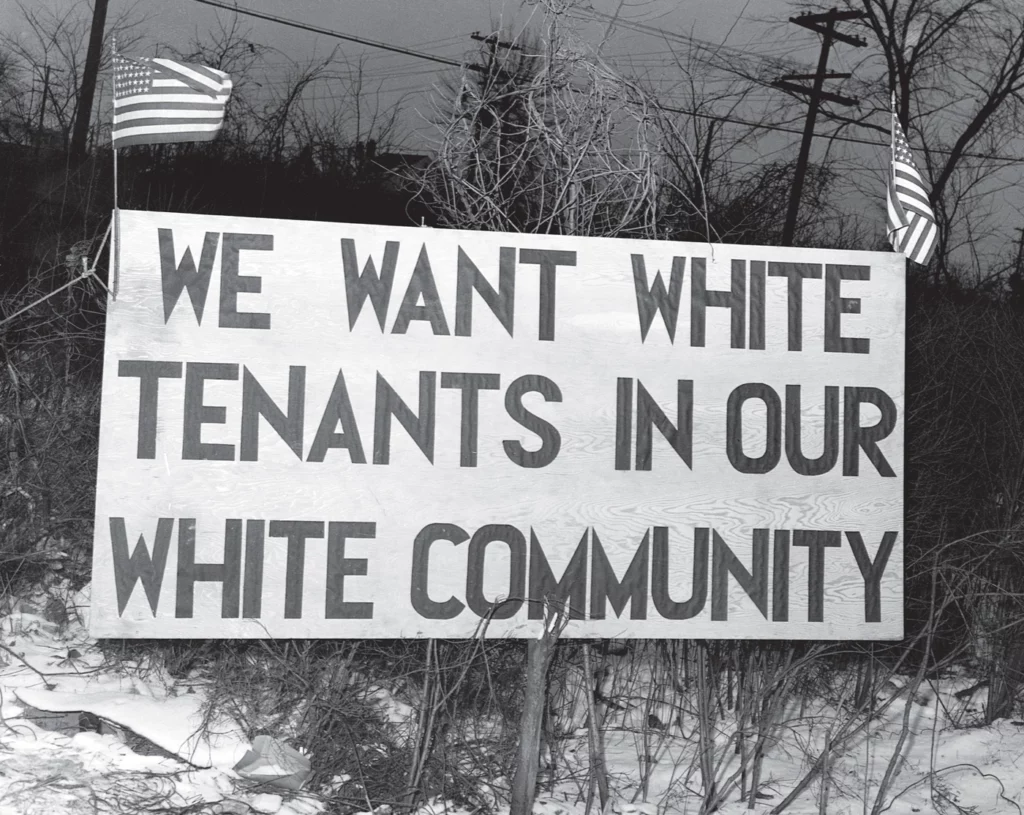

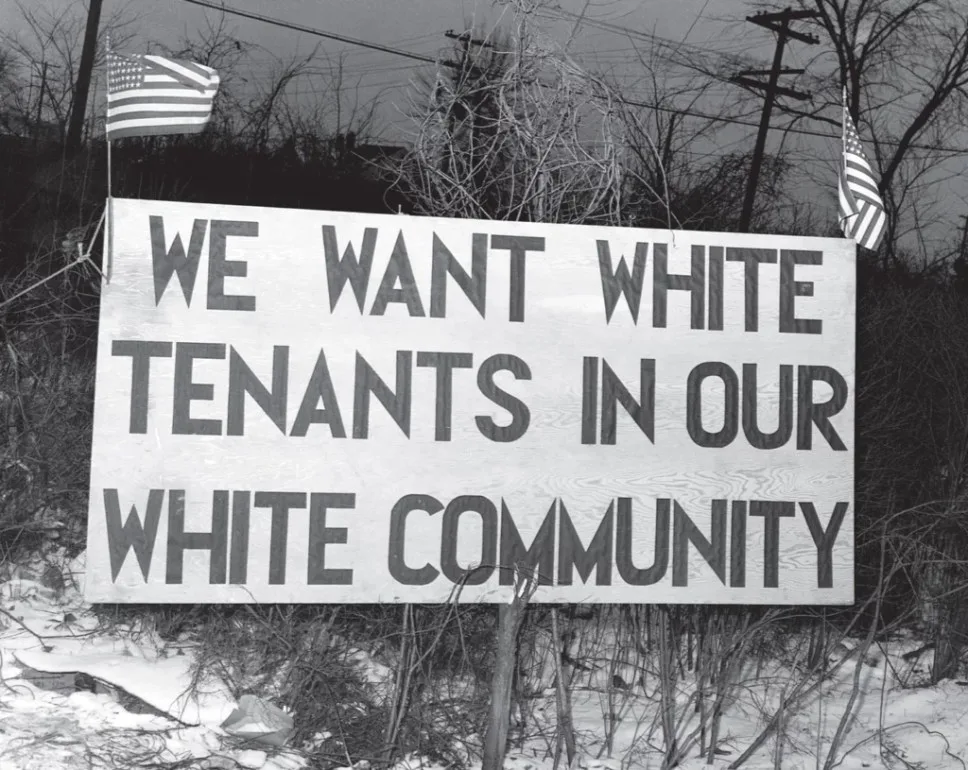

Of course, the capacity to be self-made could be significantly hindered by the circumstances of one’s birth. Members of marginalized communities had considerably less access to quality education, health care, social services, and jobs that paid living wages, or safe, secure, affordable housing. This material inequality was compounded by the reality of racial violence, which included more than 4,400 lynchings in the U.S. between 1877 and 1950.

When the stock market crashed seven months into Hoover’s presidency, he initially eschewed government-backed market or public benefit interventions, instead doubling down on white supremacist tactics of the past: scapegoating Mexican immigrants, accusing them of overwhelming government relief programs, and taking jobs that would otherwise be going to white Americans. In reality, less than 10% of recipients of government aid were Mexican immigrants or Mexican Americans, and studies would later suggest these federal repatriation drives actually harmed the economy by reducing the demand for other jobs. Conservative estimates state that between 1 million and 1.8 million people were deported during this time, as many as 60% of whom were U.S. citizens.

Unsurprisingly, the racist policies of the Hoover administration failed to save the economy. By 1933, more than 9,000 banks had failed, and the unemployment rate hovered just under 25%. To address the budget deficit, in 1932 Hoover rolled back tax cuts for the wealthy that had cut the top tax rate from 73% to 24%. But this, and a series of additional tax increases, came too late to stave off the suffering. Even after authorizing a public works program and government-backed loans, Hoover lost the next election to Franklin Roosevelt, who ushered in the New Deal, one of the most significant public interest investments in U.S. history.

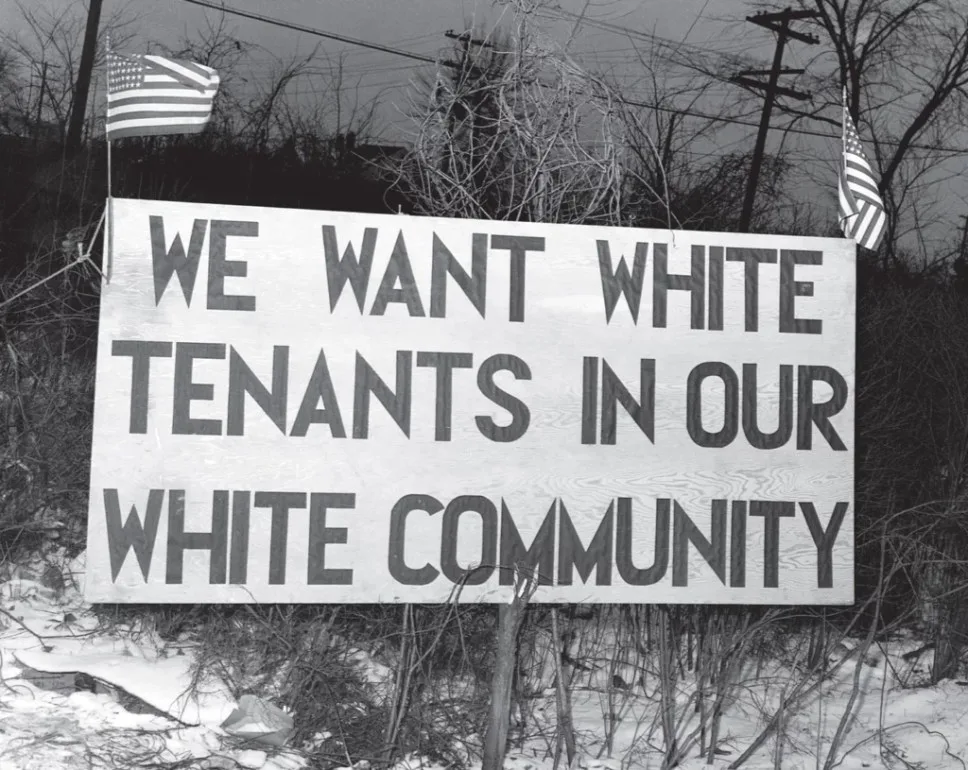

Despite its role in establishing a broad middle class, the New Deal did not create prosperity for all. Black people living under Jim Crow laws were subject to legal discrimination and unable to work in a variety of fields offering decent wages. Social Security didn’t initially apply to some agricultural and domestic workers—positions likely to be held by Black people. Consequently, while 27% of white people were ineligible for Social Security in 1935, 65% of Black people were excluded. Government-sponsored redlining allowed banks to refuse loans to people in predominantly Black communities, exacerbating this unequal access to economic growth. Racial covenants in communities nationwide disallowed the sale of land or housing to Black people. This confluence of greed, white supremacy, and racialized capitalism yet again created on-ramps to prosperity that were closed to Black people.

From Yours and Mine to Ours

The COVID-19 pandemic provided the country with an opportunity to reshape our prior economic assumptions about what is—and what should be—in the public domain. When the unemployment rate surged to 14.7% in April 2020—the highest level since the Great Depression—citizens were able to access vital financial support through the CARES Act. That $2 trillion economic stimulus package provided funding for state and local governments, tax cuts for businesses, and direct payments to individuals, bringing the U.S. as close as it’s ever been to embracing Universal Basic Income. Hundreds of billions in loans were also provided to help small businesses and nonprofits keep their employees on payroll and their organizations afloat. An additional $4 trillion in funding was made available through a suite of economic legislation spearheaded by President Joe Biden’s administration, including the American Rescue Plan.

Beyond government interventions, a resurgence in mutual aid efforts further underscored our interdependence and the power of community support. Grassroots organizing and advocacy efforts worked to protect the health and safety of essential workers, and groups like the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment and the Right to the City Alliance mobilized to protect people from losing their homes during the crisis.

Many have seen the benefit of and enjoy public goods and services. Investing in these public goods—from public parks and community pools to public libraries and trash collection—increases opportunities for collective prosperity and personal enjoyment. At their best, these government-administered services provide core infrastructure that allows communities to thrive and grow, supporting both economic development and a healthy, robust democracy.

Leading advocates say expanding the scope, scale, and breadth of these government-backed public goods can create opportunities for equitable access to housing, quality education, employment, and health care. That shifted understanding of what’s possible, combined with an embrace of collective responsibility, can create a society where all needs can be met, says Angela Hanks, chief of programs at the movement-oriented think tank Dēmos. (Disclosure: Co-author Anoa Changa is the director of communications at Dēmos.)

“Public goods are the foundation of a just economy,” Hanks says. “They strengthen communities and our economy overall. Public goods also ensure a basic standard of living and help correct the power imbalance between the wealthy and everyone else.”

But Hanks notes that corporate interests and the wealthy have weaponized the cultural myth of scarcity that suggests there are not enough resources to provide for all. This remains a major barrier to expanding public provisioning, despite its popularity. “There’s still a persistent belief around scarcity in this country, which among other things is deeply rooted in racism,” explains Hanks. “And it’s what corporations and the wealthy use to talk people out of public provisioning.”

Nevertheless, action to expand public goods is already taking place. To address the crisis in diabetes care, California Gov. Gavin Newsom contracted with a nonprofit drugmaker in March 2023 to create state-label insulin, which will make the lifesaving drug substantially more affordable and, presumably, lead to fewer people having to ration their supply because of high costs.

Elsewhere, states and municipalities are proposing public banks, like the one North Dakota has run for more than a century. By servicing local governments and operating in the public interest—by law—these entities could slash the huge sums governments now pay to private banks. Restoring postal banking, which the U.S. offered from 1911 to 1967, could help to service the 5.9 million unbanked and 18.7 million underbanked households in the U.S.

Reimagining prosperity demands a new economy that reflects shared values and a commitment to success and well-being that exists outside of an individual framework. This new prosperity also requires a grounded understanding of people and places, and a value alignment that sees the potential and possibility in something better.

John Muhammad, a city councilmember in St. Petersburg, Florida, believes traditional measures of prosperity, like GDP, are insufficient to assess well-being. “Reimagining prosperity requires going beyond traditional economic measures and considering a more comprehensive approach that aligns with the needs of the community, our well-being, health, and access to things like fresh food, education, and health care,” Muhammad says. “Growth usually means the economy is getting bigger and we’re producing more goods and services. But we need to make sure that this growth benefits everyone, not just a few people. Reimagining growth means making sure that as the economy grows, everyone has a chance to do well and improve their lives.”

Growth usually means the economy is getting bigger and we’re producing more goods and services. But we need to make sure that this growth benefits everyone, not just a few people. Reimagining growth means making sure that as the economy grows, everyone has a chance to do well and improve their lives.”

—John Muhammad

Muhammad has worked with St. Petersburg’s South Side community to revitalize a once-thriving business district. He was instrumental in negotiating a deal with the city that required new development to include actual land ownership, not mere complimentary square footage or discounted rents on spaces to lease.

“It’s important to negotiate in terms of acres and ownership when discussing community participation in new development, because that’s the only way to truly build equity and generational wealth,” Muhammad says. “Some of the historical ‘deals’ that have been made expire after a prescribed term, and when that ends and the capital is extracted from the community, we are left with little to nothing to pass on to those who come behind us.”

Communities in Detroit know those extractive processes all too well. Branden Snyder, executive director of Detroit Action, a multigenerational, member-led grassroots organization fighting for housing and economic justice, says the whole economic system needs to change.

“There are so many systems that extract and exploit Black and Brown folks outside of just the criminal justice system, including … how we set up our economies,” says Snyder. Through its Agenda for a New Economy, Detroit Action works to “unite Black and Brown working-class Detroiters in a transformational program to win the economic and social justice we are owed.”

“Detroit is called the Motor City, but Detroit isn’t about cars,” says Anthony Baber, Detroit Action’s communications and culture director. “The city itself was never about cars. City is about the people.”

“We’re still trying to empower our people using that same white supremacist lens that destroyed our ecology and left all these young Black and Brown people with little to no access to advantages and prosperity,” Baber adds. “We have to change the entire thing.”

“At the end of the day, we need to make sure that resources are shared equitably and fairly,” says Snyder. “And right now, that’s just not the case. When we think about tax breaks, the type of jobs that people get, the type of opportunities that come into neighborhoods, the type of development, and we think about the resources that people have—it’s not shared in an equitable fashion.”

Both agree that reimagining prosperity requires a strong equity component to ensure people can thrive and envision the possibility of something better. Giving people a meaningful voice in how their economy and politics are structured is as much a matter of shifting culture as it is shifting the policies and frameworks that enforce the status quo view on wealth and prosperity.

“A big part of it is just changing the mindset to one of abundance and that resources are there,” says Baber. “It’s just a matter of, can we secure those resources for our people?”

Tartt, the West Virginia farmer, agrees that both a culture shift and values realignment are necessary in the practical application of prosperity doctrines, as well as in our collective imagination. And part of that includes establishing new pathways for partnership across communities.

“If we want to really talk about prosperity, that means investing back into the community and building businesses in a way that community is benefiting,” he says. “There are opportunities if you have rural communities connected to urban communities. And we’re figuring out: How do we help each other?”

This story was funded by a grant from Kendeda Fund, as part of the forthcoming YES! series “Redefining Prosperity.” While reporting and production of the series was funded by this grant, YES! maintained full editorial control of the content published herein.

|

Ericka Taylor

is the popular education manager for the Take on Wall Street campaign of Americans for Financial Reform. She has more than 25 years of experience in popular education, organizing, and advocacy. Taylor is a regular review contributor to NPR Books, and her writing has appeared in Willow Springs Magazine, Bloom, and The Millions. She currently sits on the board of directors for the PEN/Faulkner Foundation. She is based in the Washington, D.C., area, and speaks English. |

|

Anoa Changa

is a communications strategist, movement journalist, and former attorney who is now the communications director at Dēmos. She has been published in several outlets including NewsOne, Truthout, The Appeal, Essence, and Scalawag magazine. A retired attorney, she also hosts The Way with Anoa podcast. She is a member of the National Association of Black Journalists. |