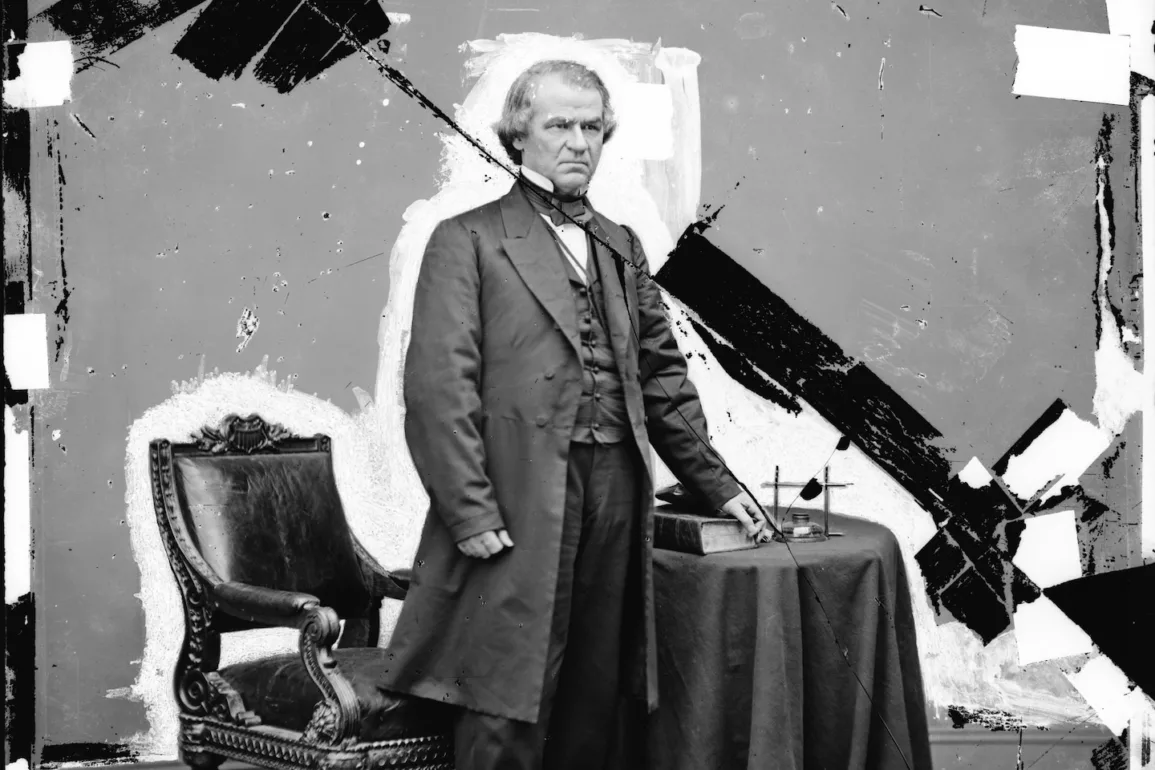

After Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 — establishing citizenship for newly emancipated slaves — President Andrew Johnson vetoed it, voicing concern that it was “made to operate in favor of the colored and against the white race.”

But lawmakers overrode his veto, enacting one of nation’s first building blocks of an equal society.

Now, 157 years later, the law has become central to the legal battle over what is fair and equal when it comes to race in the workplace. In recent years — and especially since the Supreme Court overturned race-conscious college admissions in June — the Reconstruction-era law has emerged as a critical tool for conservatives intent on dismantling race-specific programs that promote “diversity, equity and inclusion,” or DEI.

More than a dozen lawsuits — nearly all filed within the past three years — use the law to allege reverse discrimination. The plaintiffs include former employees at major companies, small-business owners, government contractors, college undergraduates and conservative activists. All say they’re fighting for a colorblind society, and that programs intended to bolster economic participation for certain racial and ethnic groups have unfairly shut out Whites and, in some cases, Asians.

Critics call these claims a perversion of the law’s original intent. It’s ironic, they say, that legislation meant to grant former slaves basic civil rights — and make it illegal to deprive them of those rights because of their race or color — is being used to stifle advancement by Black and minority professionals and entrepreneurs in industries in which they have long been underrepresented. Moreover, affirmative action was meant to redress centuries of discrimination, not punish Whites or Asians.

Even with such programs, people of color are vastly underrepresented in the top tiers of the business world: There’s only eight Black CEOs among Fortune 500 companies — the highest number since the list started in 1955. And of the $214 billion in venture capital funding allocated in 2022, a scant 1.1 percent went to companies with Black founders, according to Crunchbase.

Whatever happens, the law’s disparate applications mirror the nation’s fitful civil rights history. A recent wave of reverse-discrimination lawsuits could prohibit the private sector from using race-based affirmative action and DEI programs in light of theSupreme Court’s finding that race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina contradicted constitutional promises of equal protection forged after the Civil War.

“That’ll be an easy case” for the high court’s conservative majority, said Michael J. Klarman, a professor of legal history at Harvard Law School. And they’re “not interested” in arguments that recent application of such laws is “unbelievably perverse.”

Listed as Section 1981 in the federal code, the 1866 law has been cited in lawsuits against Pfizer, Morgan Stanley, Amazon, Gannett, a pair of global law firms and a venture capital fund for women of color. All challenge the use of racial preferences, whether in deciding who to hire, selecting contractors or awarding fellowships.

John Yoo, a law professor at the University of California at Berkeley who sits on the board of the conservative Pacific Legal Foundation, rejects the idea that such lawsuits distort the intent of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

Lawmakers “didn’t write the text of the statute … to be limited in time — or to protect only one race,” he said.

Black codes

When the 13th Amendment outlawed slavery in 1865, it left the newly emancipated in legal limbo because a “slave was not a ‘person’ in the contemplation of the law,” wrote New York lawyer Robert L. Kohl in a 1969 Virginia Law Review article. “He had no personal or ‘civil’ rights.”

This ambiguity created an array of legal “disabilities,” leaving the newly freed without the right to marry, inherit property or take legal action. It also gave rise to a patchwork of “black codes” in the South — laws meant to oppress and control them.

“The whites know that if negroes are not allowed to acquire property or become landowners, they must ultimately return to plantation labor, and work for wages that will barely support themselves and families, and they feel that this kind of slavery will be better than none at all,” wrote a Freedmen’s Bureau official in a letter included in the 1865 report to Congress on the “Condition of the South.”

The Black Codes purported to be about protecting the rights of Black people, but they were “actually a way of functionally re-enslaving them by requiring them to sign contracts,” Klarman said. “If they didn’t sign contracts, they’d be treated as vagrants. If they’re vagrants, they would be arrested and then sold off essentially to the highest agricultural bidder.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was partly a response to the Black Codes, as well as to the legal disabilities. It guaranteed a bevy of rights, equal to those “enjoyed by white citizens” — including the ability to buy and sell property, sue and be sued, provide evidence, and make and enforce contracts.

In short, the law was meant to address the question of citizenship for the formerly enslaved, said George Rutherglen, a law professor at the University of Virginia. “And the statute answers the question: They’re going to be treated just like White citizens.”

Two years later, Congress passed the 14th Amendment, guaranteeing citizenship to anyone born or naturalized in the United States — including formerly enslaved people — ensuring equal protection under the law.

Both measures were seen as a radical remaking of American society, Rutherglen said. But enforcement fell away soon after the federal government pulled its soldiers out of Southern states in the late 1870s. Then Jim Crow laws took hold, ushering in a strict system of racial segregation that stretched far into the next century.

‘Whites as well as nonwhites’

The 1866 Civil Rights Act faded into obscurity for nearly 100 years — until a interracial couple tried to buy a home in St. Louis in 1965. That June, Joseph Lee Jones, who was Black, and his wife, Barbara Jo Jones, who was White, were advised by a real estate agent for the Alfred H. Mayer Co. that it was the company’s “general policy not to sell houses and lots to Negroes.”

The couple sued, citing the law, and the case reached the Supreme Court in April 1968. Justices, who heard arguments days before the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., ruled 7-2 in Jones’s favor, holding that private parties could not discriminate against Black people in the sale of property.

Legal historians say the 1866 Civil Rights Act was revived by the Jones decision, which interpreted the law as one prohibiting discrimination by private parties.

Nearly a decade later, two White men used it to claim discrimination.

The 1976 landmark case involved White workers L.N. McDonald and Raymond Laird, and a Black colleague, Charles Jackson, who had been charged with stealing 60 gallons of antifreeze being transported by the Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co. While Jackson was allowed to keep his job, Laird and McDonald were fired. They sued, alleging discrimination under the 1866 Civil Rights statute, and their case landed before the Supreme Court.

The court ruled 7-2 in their favor. Writing for the majority, Thurgood Marshall — the first Black Supreme Court justice and a legendary civil rights figure — said the law was intended to apply to “all persons,” including White people.

The context of emancipation notwithstanding, “the general discussion of the scope of the bill did not circumscribe its broad language to that limited goal,” Marshall wrote in McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co. “On the contrary, the bill was routinely viewed, by its opponents and supporters alike, as applying to the civil rights of whites as well as nonwhites.”

It is this interpretation that gives the 1866 Civil Rights Act so much power in the present campaign to end private-sector affirmative action programs, experts say.

The Fearless Fund

Most reverse discrimination lawsuits citing the 1866 law concern fellowship or grant programs restricted to specific underrepresented groups. That includes one filed in August by America First Legal — a legal nonprofit founded by former Trump administration adviser Stephen Miller — against Progressive Insurance’s Small Business Forward Fund, which awards $25,000 grants to Black-owned businesses. The group also has alleged that a small-business accelerator program run by Amazon discriminates against Whites. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post, whose interim chief executive, Patty Stonesifer, sits on Amazon’s board.)

But these arguments have perhaps most vividly played out in a case against the Atlanta-based Fearless Fund, a venture capital firm for women of color. In August, a group led by affirmative action opponent Edward Blum — the driving force in the Harvard and UNC lawsuits — sued the fund alleging that its $20,000 grant program for Black female entrepreneurs discriminates on the basis of race, a violation of the 1866 Civil Rights Act.

In September, a panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit temporarily blocked the grant process from moving forward, ruling that it would likely violate the law. The 11th Circuit is expected to rule on whether the fund can proceed with its grant program as the court case is litigated.

Blum, reacting to a lower court’s decision in September, said that the nation’s “civil rights laws do not permit racial distinctions because some groups are overrepresented in various endeavors, while others are underrepresented.”

But critics insist that Blum and others driving similar challenges have distorted the law’s intent, wielding it as a cudgel against fair opportunity for racial minorities, especially Black people.

“This is a seminal civil rights statute, passed right after the Civil War, to ensure that the newly freed people who were slaves have the same rights as everybody else,” Jason Schwartz, a lawyer with Gibson Dunn, a law firm defending the Fearless Fund, said in a recent interview. “And to try to use that statute as a weapon against Black people … is outrageous.”

Judge Charles R. Wilson, who was appointed to the 11th Circuit by Bill Clinton, made a similar argument in his September dissent from an appellate panel’s decision to temporarily halt the Fearless Fund’s grant program.

“It is a perversion of congressional intent to use [the law] against a remedial program whose purpose is to ‘bridge the gap in venture capital funding for women of color founders’ — a gap that is the result of centuries of intentional racial discrimination,” he wrote.

But the two other judges on the panel — Robert J. Luck and Andrew L. Brasher, both Donald Trump appointees — described the program as “racially exclusionary,” concluding it would “substantially likely” violate the 1866 law if grants were awarded.

The judges quoted Marshall’s opinion in the 1976 McDonald case: “The Supreme Court has held that Section 1981 ‘was meant, by its broad terms, to proscribe discrimination in the making or enforcement of contracts against, or in favor of, any race.’”

Colorblind society

Legal scholars say the lawsuits citing the 1866 Civil Rights Act — as well as those that reference Title VII of 1964 Civil Rights Act — have a strong chance of eliminating race-conscious programs in the private sector.

“The lawsuits are aimed at wiping out any vestiges of what we call affirmative action in employment,” said Susan Carle, a law professor at American University and an expert in Reconstruction-era history. The law is being used because it carries a “constitutional overtone” that could ripple into other areas of the law that protect private-sector affirmative action and DEI programs, she said, adding: “I very much fear that they will prevail.”

These lawsuits already are having an effect. After Blum’s group, the American Alliance for Equal Rights in August sued the Perkins Coie and Morrison Foerster law firms, both opened their diversity fellowships to law students from all backgrounds. The suits were later dropped.

In October, Adams and Reese, another international law firm, discontinued its fellowship for minorities after Blum sent a letter threatening litigation. And one of the firms representing the Fearless Fund, Gibson Dunn & Crutcher, has opened its diversity fellowship to all students. Neither had been sued.

Last week, Blum’s group sued the law firm of Winston & Strawn, alleging its fellowship program discriminates against straight White men. These lawsuits are notable in an industry that has long struggled to diversify its workforce: Blacks represent less than 5 percent of practicing attorneys, according to the American Bar Association, compared with 14 percent of the U.S. population.

The strategy being deployed by Blum, America First Legal and other groups is a winning one, Rutherglen noted. It was pioneered at the advent of the civil rights movement by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, which secured the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision that ended segregation in schools. The fund’s leader at the time, Thurgood Marshall, argued the case before the high court.

“They’re following the same strategies that … Marshall followed,” Rutherglen said. “They’re just doing it to pursue a conservative agenda.”

Darrell A.H. Miller, a law professor at Duke University, said there are a couple of ways to think about the 1866 law’s arc. “If you’re a cynic,” he said, it “reinforces the idea that African Americans in particular would never benefit unless there’s something in it for the dominant racial group.”

The less cynical view is one held by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., Miller said. Writing the majority opinion in the Harvard-UNC case, Roberts said: “Scratching the sore of American’s sordid racial history never does anybody any good, and the way to stop discriminating on the basis of race is to treat every issue as if race didn’t matter.”

“I don’t think that they have bad intent. I think they genuinely believe that a colorblind society will naturally and ineluctably lead to a more equitable society,” Miller said. “All I can say is: The history of America makes me somewhat skeptical.”