ST. HELENA ISLAND, S.C. — Michael B. Moore sat down, closed his eyes and lowered his head. The pastor standing behind him clamped his palm on Moore’s shoulder, and three women rested their hands on his back and arms. They sang, prayed and shouted “Hallelujah!”

They gave their blessings knowing that the political road ahead would be difficult for Moore, a great-great-grandson of a Civil War hero who commandeered a Confederate steamer to escape slavery before serving five terms in Congress. Moore, 61, hopes to follow in his ancestor’s footsteps by winning a House seat as a Democrat here in South Carolina.

One woman leaned toward Moore’s face, gripped his hands and knelt to pray. Another placed her hand on his head as the candidate wiped tears from his eyes.

“There’s absolutely nothing that can harm you,” the woman thundered. “We don’t care about no gerrymandering.”

Many fellow Democrats lack her confidence. This spring, the Supreme Court signed off on district lines in South Carolina that Republican state lawmakers said they had designed to benefit their party. The 1st District, held for the last four years by Rep. Nancy Mace (R), had previously been competitive but is now ranked solidly Republican by the nonpartisan Cook Political Report after the redrawn lines placed more Republican voters in the district and ensured the share of Black voters would not rise, staying at 17 percent.

A federal three-judge panel last year found that the district lines represented an unconstitutional racial gerrymander that “exiled” to a neighboring district tens of thousands of Black voters who overwhelmingly vote for Democrats. But Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., writing in May for a six-justice Supreme Court majority consisting entirely of GOP nominees, contended there was little evidence that South Carolina lawmakers had focused on race as they drew lines to maximize a Republican edge. Gerrymandering for partisan advantage, the court has previously ruled, cannot be blocked by federal courts.

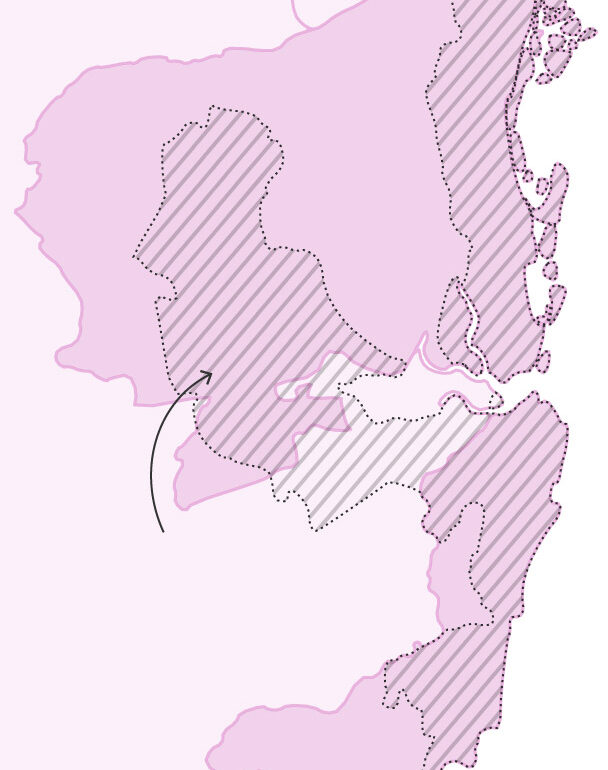

How South Carolina’s 1st District changed

In May, the Supreme Court ruled that the new district lines did not represent an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, overturning an earlier finding by a federal three-judge panel.

7TH DISTRICT

1ST DISTRICT

2022-present

Charleston

2011-2022

1st District

6TH DISTRICT

1ST DISTRICT

2022-present

Source: All About Redistricting

JANICE KAI CHEN/THE WASHINGTON POST

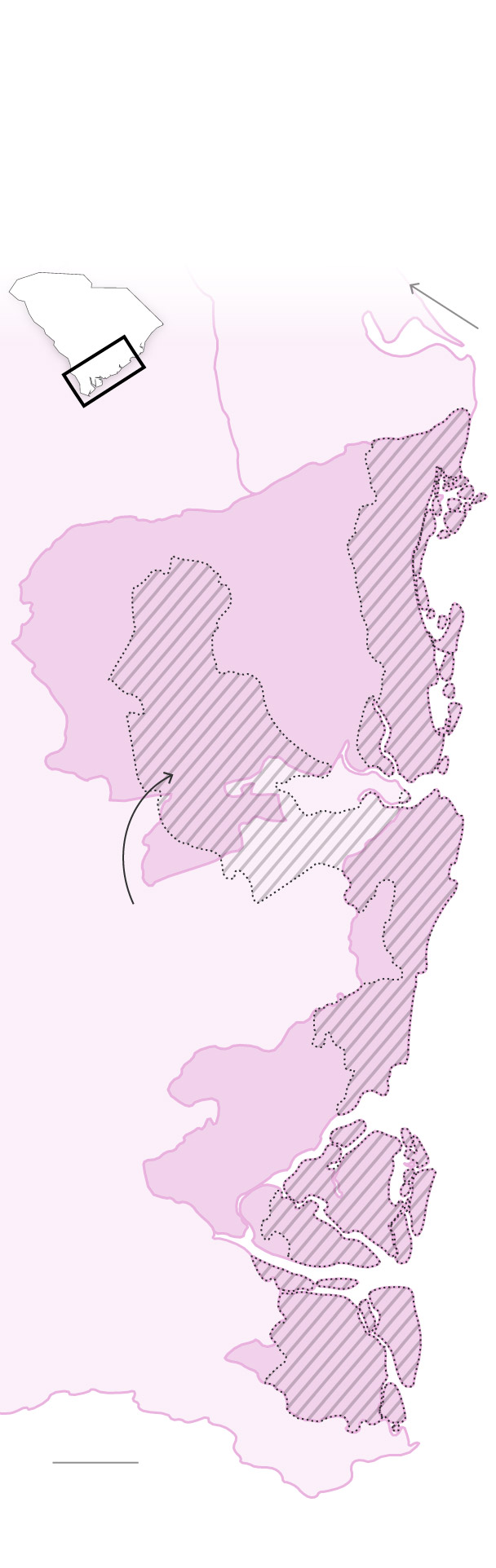

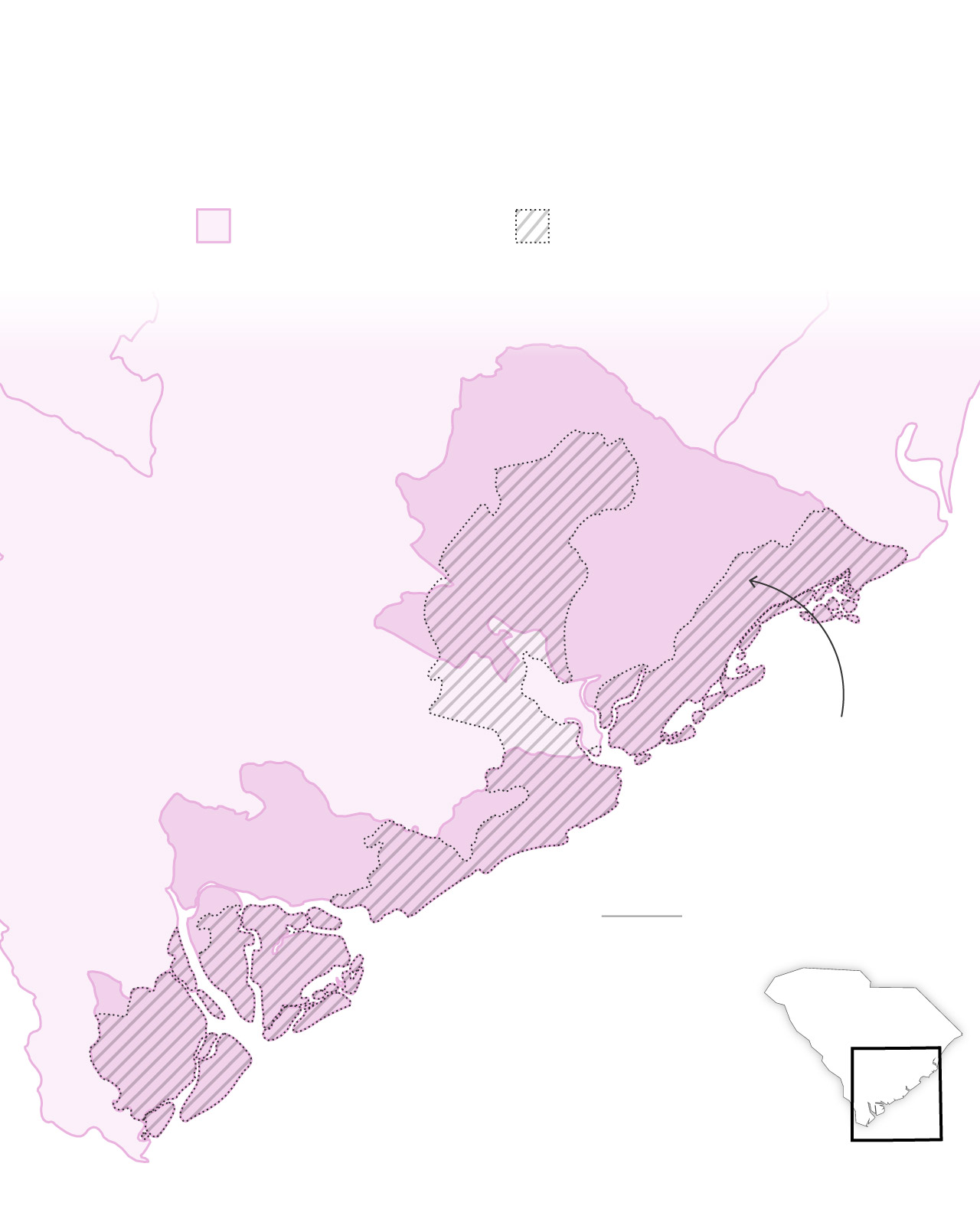

How South Carolina’s 1st District changed

In May, the Supreme Court ruled that the new district lines did not represent an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, overturning an earlier finding by a federal three-judge panel.

2022-present districts

2011-2022 1st District

7TH DISTRICT

1ST DISTRICT

2022-present

6TH DISTRICT

Charleston

2011-2022

1st District

1ST DISTRICT

2022-present

Source: All About Redistricting

JANICE KAI CHEN/THE WASHINGTON POST

In a blistering dissent, Justice Elena Kagan wrote that the majority had cleared the way for discrimination by giving states a green light for “using race as a short-cut to bring about partisan gains.”

The majority decision is the latest in a string of rulings under Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. that have made it significantly harder to challenge redistricting plans and voting laws. For Black voters, who have long struggled to gain full political representation in America, the decisions have narrowed what had once been a productive path for ensuring they get equal say.

“For minority voters, for people who believe in partisan fairness, federal litigation just isn’t the answer under the Roberts court,” said Harvard Law School professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos.

The South Carolina decision will help Republicans as they try to maintain their narrow control of Congress this fall. In future elections elsewhere, the ruling could cut both ways, legal analysts say, helping Republicans in some instances but preventing them in others from challenging boundaries that are drawn to benefit Democrats.

In South Carolina, the ruling effectively locked in a 6-to-1 House advantage for the GOP in a state that Donald Trump won in 2020 with 55 percent of the vote. The lone Democrat, Rep. James E. Clyburn, is also the only Black South Carolina House member, and his district is the only one in the state with a plurality Black population. Statewide, just over a quarter of the population is African American.

The disconnect between the race of voters and those who represent them is even starker in some other Southern states, where the share of Black federal and state legislators is significantly lower than the share of the Black population.

Moore is waging an against-the-odds campaign to give South Carolina its second Black Democrat in Congress.

Before receiving his blessing, the candidate stood before about 50 people at Gullah Grub, a coastal restaurant known for its gumbo and barbecue chicken. For an hour he made an upbeat case for curbing gun violence, bolstering green-energy programs, guaranteeing a right to abortion and scaling back gerrymandering. He talked about his work as a businessman, his experience getting the International African American Museum off the ground in Charleston and his family ties to Robert Smalls, who piloted ships for the Union in the Civil War before joining Congress during Reconstruction.

Those battles, he said, included the long struggle to ensure that Black people can participate fully in democracy.

“There are very serious threats to democracy that we all know are going on — even in this district, where 30,000 Black folks were gerrymandered out of the district,” he said. “Either we believe in the notion of ‘one person, one vote’ or we don’t.”

The district stretches along South Carolina’s coast, starting about 50 miles north of Charleston and meandering south past Hilton Head and down to the state’s border with Georgia. Not too long ago, it was competitive. In 2018, Democrat Joe Cunningham won with 50.7 percent of the vote. Two years later, Mace beat Cunningham by a similar margin, underscoring the district’s swing status.

Like all states, South Carolina had to draw new lines after the 2020 Census to ensure that its congressional districts had roughly equal populations. Mace’s district was overpopulated, and Clyburn’s neighboring district was underpopulated by similar numbers.

State lawmakers could have equalized their populations by moving about 85,000 voters from Mace’s district to Clyburn’s, court records show. Instead, they shifted tens of thousands of voters out of Clyburn’s underpopulated district, exacerbating the population disparity. Lawmakers then imported tens of thousands of other voters into his district from Mace’s. In all, they moved about 193,000 voters, more than twice as many as needed to balance the populations of the two districts.

In the process, they carved up the Charleston area, cleaving some largely Black neighborhoods and making Mace’s district much safer for Republicans. Mace cruised to victory in 2022 with 56.5 percent of the vote.

Black voters represented by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund sued, and a panel of federal judges last year ruled that lawmakers had unconstitutionally gerrymandered the district by engaging in a “bleaching” of the district. Republican state lawmakers said they had drawn the maps for political reasons, not racial ones, and they appealed to the Supreme Court.

Under past rulings, states are barred from engaging in racial gerrymandering but have wide latitude to draw district lines for partisan gain. Race and partisanship are often intertwined, creating challenges for courts as they try to determine the motivation for how lines were established.

In the May ruling, Alito wrote that courts should assume that state legislatures are acting in good faith and trust that they are drawing lines based on politics, not race. Those who challenged South Carolina’s map were focusing on race to “sidestep” the Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling that allowed partisan gerrymandering, Alito wrote. “They provided no direct evidence of a racial gerrymander, and their circumstantial evidence is very weak,” he wrote.

Justice Clarence Thomas went further in a concurring opinion, writing that the court should not consider gerrymandering cases and should leave line-drawing to legislatures. He said the case reduced Black voters to “partisan pawns and racial tokens” in part because the plaintiffs had not properly taken stock of the election of Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.), the first Black senator from the South since Reconstruction.

In her dissent, Kagan pointed to court testimony showing that when mapmakers drew their lines, their computers displayed data illustrating how moving any line would change the racial demographics of the district. “Why configure a computer to tell you, at every stage of the mapmaking process, how the slightest change in a district line would affect Black voting-age population if you weren’t tracking and manipulating Black voting-age population?” Kagan asked.

Gerrymandering has helped to diminish the number of competitive seats nationwide: In open House races, the number of landslides has roughly doubled in the past four decades.

Different boundaries probably would have turned Mace’s district into swing territory, with neither party having a lock on it. That would have benefited residents, the plaintiffs argued.

“It’s not just that they would have a competitive district,” said Allen Chaney, the legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of South Carolina and a lawyer in the case. “It’s that because they would have a competitive district, whoever wins that election, whether it’s a Republican or a Democrat, knows that they have to, in some meaningful way, go to Congress with the concerns of folks in Charleston.”

Politicians finding ways to draw maps that help them is nothing new, said Ilya Shapiro, the director of constitutional studies at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank. He said the Supreme Court recognized that reality in its May decision by forcing those challenging maps to meet the high bar of demonstrating that gerrymanders are based on race rather than politics or something else.

“It was meant to underline the point that we’re not going to police political gerrymanders,” Shapiro said. “So if you have an allegation of a racial gerrymander, prove it.”

Eleven years ago, the Supreme Court ended the requirement that South Carolina and other states with a history of discrimination get approval from the Justice Department or a court before changing district lines and election rules. It followed that decision with rulings that allowed states to more freely engage in partisan gerrymandering and made it harder to challenge voting rules that disproportionately affect Black and Hispanic voters.

The rulings have thrilled conservatives as Republican-led states have sought to redraw district lines and tighten voting policies. But they have also empowered Democrats to draw better lines for themselves in states they control.

While the litigation in South Carolina failed, lawsuits by Black voters in some other states have succeeded. The Supreme Court last year ruled that Alabama needed to draw another congressional district where Black voters could elect a candidate of their choice. And last month it allowed the use of a new map in Louisiana that includes two districts with Black majorities instead of one.

About three weeks after the Supreme Court ruled in the South Carolina case, Moore won his primary race.

“The general election will be grueling, and we will face formidable challenges,” he told his supporters the night he clinched the Democratic nomination. “We’ve already been impacted by a South Carolina General Assembly and a Supreme Court that did everything they could to steal this seat. But I’m confident that with the same spirit of determination and unity that brought us thus far, we will prevail.”

His supporters clung to hope. Anita Singleton-Prather, the woman who had referenced gerrymandering when she prayed over Moore four days earlier, said Black people “don’t have the option of giving up.”

“We made it through the Middle Passage,” she said. “We made it on the auction block when our family members [were there]. We made it at the whipping posts. We made it through the lynching period. We made it through Jim Crow. And we’ll make it through gerrymandering.”

Moore’s great-great-grandfather was elected to Congress in 1874, six years after South Carolina adopted a state constitution that gave Black men the right to vote. At the time, nearly 60 percent of the state’s population was Black, and every congressional district in South Carolina had a Black majority, according to a legal brief from historians filed in the recent Supreme Court case.

The successes that Smalls and other Black politicians saw were short-lived. By 1882, state lawmakers had stripped power from Black voters by packing them into a single district that critics compared to a boa constrictor because it snaked along the coast and into the interior of the state.

Smalls held that seat at the end of his career, when he was the only Black member of Congress from South Carolina. Other Black congressmen followed him and held the seat into the 1890s. After that, nearly a century passed before South Carolina voters sent another Black representative to the House by electing Clyburn.

The Rev. Kenneth Hodges said he kept that history in mind when he joined in the prayer for Moore. A former state lawmaker, Hodges is the pastor at Tabernacle Baptist Church in Beaufort, where Smalls is buried.

“Some of the same challenges that Robert Smalls faced towards the end of Reconstruction, we are experiencing them again,” Hodges said. “It just makes the battle harder, but we will prevail.”