By Raymond Jones

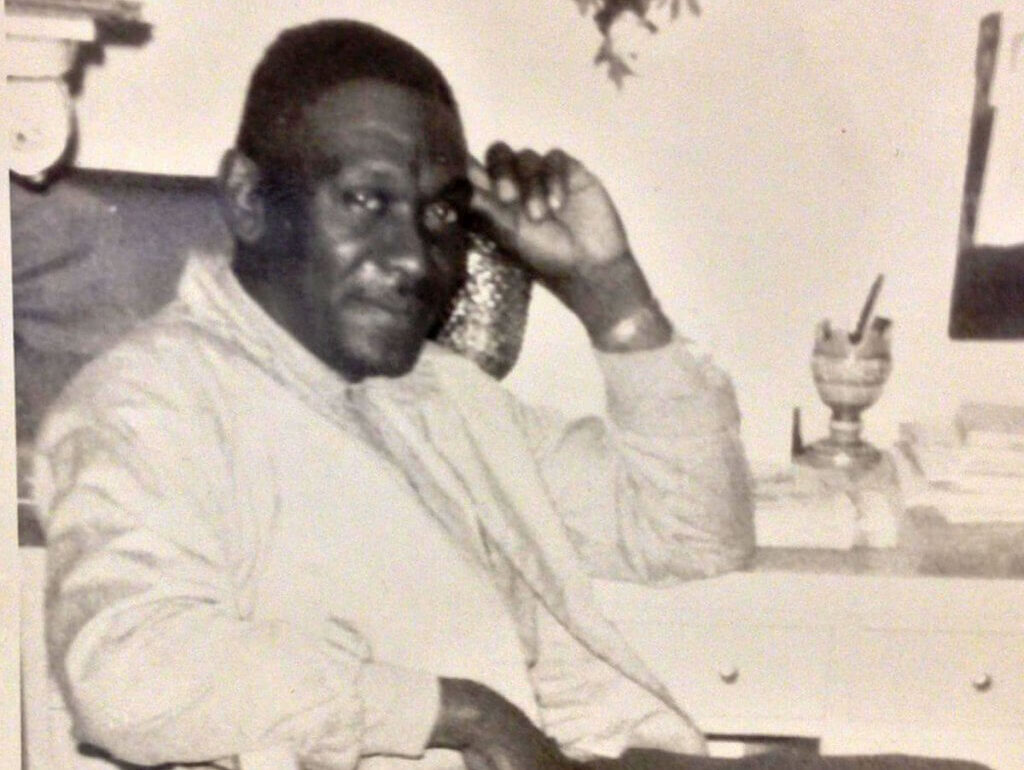

ABOVE PHOTO: Perryman Construction president/CEO Angelo Perryman

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ‘60s, when Black churches were systematically being firebombed and burnt to the ground, a Black construction firm with Philadelphia ties was providing opportunites for Black construction professionals to help restore those churches across the South.

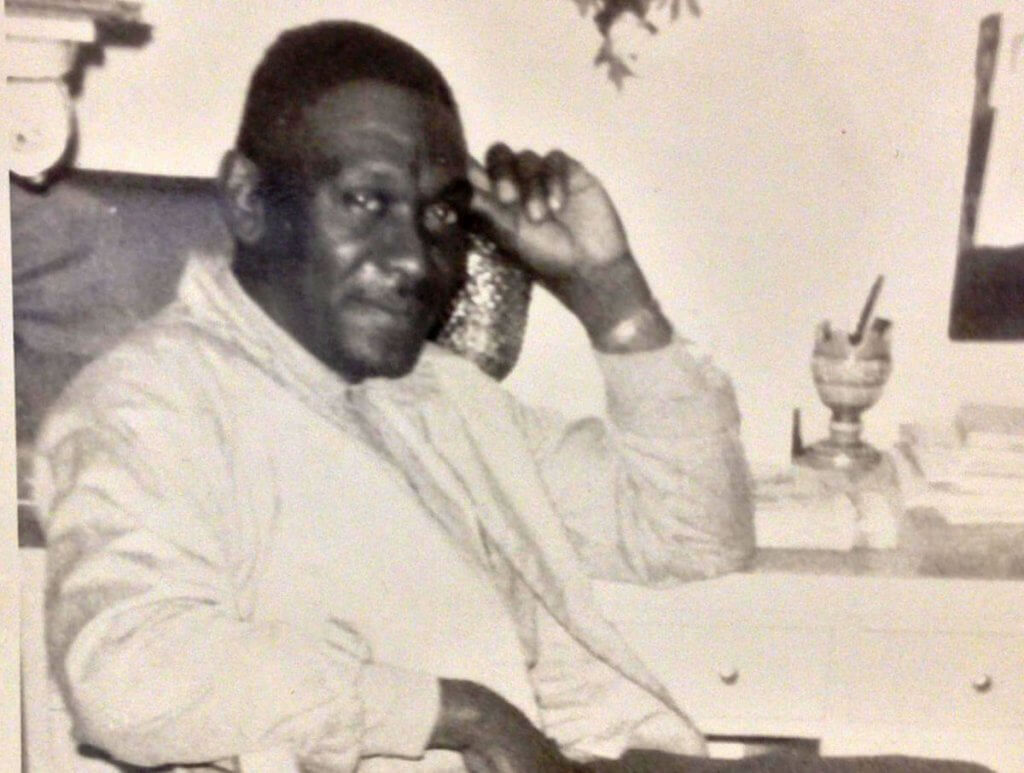

Perryman Construction founder Jimmy Perryman

Jimmy Perryman, known for showing up to construction sites with toolbox-in-hand, began his construction firm in 1954 in Alabama during those turbulent years. Now, 70 years later, Jimmy’s son — Angelo Perryman — is president and CEO of Perryman Building and Construction, Inc., where he is continuing the tradition of providing opportunities for Black construction professionals in Philadelphia.

“When I came to Philadelphia in the ‘80s, we made it our business to find talent in the area giving people an opportunity,” Perryman said.

Angelina Perryman, the vice president of administration, Perryman Construction

Perryman is thoughtful and introspective as he talks about the seven-decade growth of his company. He is introspective regarding the lessons he learned early in his career by watching his dad work.

“My dad believed that a quality job performed by quality people always counts,” he said.

The Southern lilt in Perryman’s voice as he speaks about his father reminds anyone who is listening of the family’s original Alabama roots.

The buildings created by Perryman Construction; West Oak Lane Charter School, LeBus Cafe’, and their latest project in development, Lewis C. Cassidy Academics Plus

Photos courtesy of Perryman Construction

Thousands of people every year in Philadelphia walk through the doors of buildings that the Perryman Construction firm built. Their successful portfolio includes Philadelphia International Airport, The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, The Philadelphia Zoo Garage, and Lincoln Financial Field. Perryman’s daughter, Angelina Perryman, is the vice president of administration for the company.

“One of the [advantages] of working with family is that I have walked the road my children are traveling. We pride ourselves in hiring the first African American carpenter foreman on a job and the fact that, on any given project, we have at least 85% Black and women participation on [those] projects,” Perryman said.

Perryman’s road to Philadelphia first began as a construction professional throughout the country. Early in his career, he helped build a papermill manufacturer in Savannah, Georgia, supported projects in San Diego, California; Detroit, Michigan and Alaska. These various projects prepared him for his success of building a solid 20-year reputation before coming to Philadelphia.

“My motto from my mother — pray, plan, and proceed — has become the way in which I continue to do business,” Perryman said. “It continues to serve me well.”

Perryman relocated the business to Philadelphia in 1989. The move was a direct outgrowth of the intersection of politics, opportunity and access during Mayor W. Wilson Goode’s administration.

While Atlanta, Georgia had become the standard template of how to create opportunities so African American businesses can flourish in an urban landscape during the Maynard Jackson era in the late 1970s (Jackson was Atlanta’s first Black mayor), Perryman became involved in the 1980s because of Goode, the first African American mayor in Philadelphia.

Perryman construction is in a class of its own as an African American owned construction firm, according to Omar Shareef, director of the African American Construction Association in Chicago.

“You are talking somewhere between 5 or 6% of the building construction firms in America that are owned by African Americans,” Shareef said. He added that what makes firms like Perryman successful is the commitment to the craft of building.

“When you like what you do, it becomes a mission. A mission is a lot more important to you than a hustle,” Shareef said. He also said that African American firms that work hard with mainly white developers to broaden the viability and visibility of hiring African American firms, provide more opportunity for all Black construction firms. Perryman said that one of the challenges confronting African American builders is having enough work to keep you financially afloat and expanding the label of being considered just a minority business. During Jimmy Perryman’s time, the blatant obstacle for Black businesses and success was the constraint of Jim Crow. But Angelo acknowledges subtle obstacles still remain for Black businesses. The physical signs of Jim Crow maybe gone, but the obstacles beyond those long-removed signs remain.

“At the end of the day, it is getting access to opportunities to stay in business that often confronts African American businesses,” Perryman said. “In addition, its capacity, so you can attract large projects. You want to be known for being the best — that keeps you continually employed.”

Perryman Construction has earned the reputation of being one of the best construction firms, period —white or Black.

“When I received the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award in 2016, that was a clear acknowledgement of the work,” Perryman said. “Only three African Americans have received that award for work in Philadelphia.”

For Perryman, the award solidified his professional accomplishments and reinforced his father’s core business values for the company.

Perryman Construction has the distinction of also being among one of the oldest African American family-owned construction firms, often mentioned in the same breath as McKissack & McKissack, an African American family construction firm founded in New York in 1905.

If Jimmy Perryman could, through a time machine, walk the streets of Philadelphia, he would marvel at the work of the second and third generation owners of Perryman Construction, such as the $20 million renovation of LOVE PARK and the $60 million Cassidy School, founded by this skilled and hardworking builder who, fresh out of the Korean War, was always prepared with his toolbox.