The Tuskegee VA hospital was the first in the country to be led by an all-Black medical team. It became a hub for Black medical professionals to develop their careers.

Tuskegee VA

Tuskegee VA

TUSKEGEE, Ala. – The sprawling leafy Tuskegee VA spans more than 400 acres, and operates like a mini-city. There are outpatient medical clinics, a nursing home, a psychiatric hospital, and a mental health residential treatment program. It also has its own fire station, baseball stadium, bowling alley, and chapel that chimes on the hour.

Some of the buildings here date back a century, to a time when Black soldiers returning from World War I, found healthcare hard to come by in the U.S.

“I kind of think of this as where health equity for veterans began,” says Amir Farooqi, director of the Central Alabama Veterans Healthcare System, which includes this Tuskegee campus.

An aerial view of the historic Tuskegee VA hospital campus. It was established in 1923 specifically to treat Black veterans on land donated by nearby Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University.

National Archives

National Archives

In the early 1920s, the nearby Tuskegee Institute — a historically Black university — donated land to the federal government to build what was originally dedicated in 1923 as the “Veterans Hospital for Negro Disabled Soldiers.”

“It really is a piece of history because there was no other VA built like this,” Farooqi says. “It was built specifically for veterans of color, Black American veterans and others who were not receiving the same quality of care or access to care following WWI that they really should have been and that they deserved.”

The main entrance of the Tuskegee VA embodies the Classical Revival architectural style prevalent in the 1920s. The campus is being considered for National Historic Landmark status.

Debbie Elliott/NPR

Debbie Elliott/NPR

Fighting for health equity

He says it was especially challenging in the South due to Jim Crow laws and segregation.

At the time most hospitals were segregated by race, either in different facilities altogether or separated by ward.

“Sometimes the separate wards were in the basement, in the attic, so the question was exclusion,” says Dr. Vanessa Northington Gamble, a Medical Humanities professor at The George Washington University, and a scholar of African-American medical history.

The Tuskegee VA is celebrating its centennial. A mural in the canteen depicts key moments in the facility’s history.

Tuskegee VA

Tuskegee VA

“Black soldiers were demanding care,” she says. “The Black medical profession was pushing for this because they needed some professional affirmation that that they could run a hospital.”

The federal government pledged to build the Tuskegee hospital after mounting pressure from a national campaign by veterans, the Black medical community, the NAACP, and Black newspapers.

It opened in 1923 with 600 beds and 250 patients, with a focus on treating tuberculosis and “shell shock.” But there was controversy from the start amid a tense racial climate. Gamble says much of it centered around who was going to be in charge of the federal funding that came with the establishment of a Veterans Affairs facility.

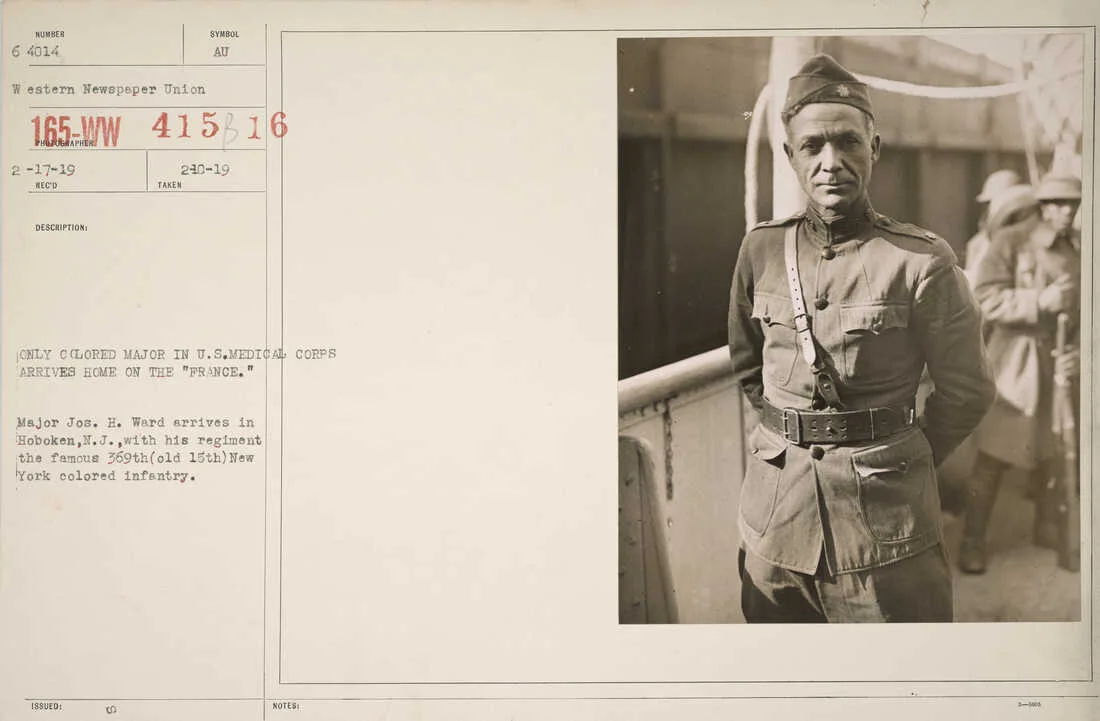

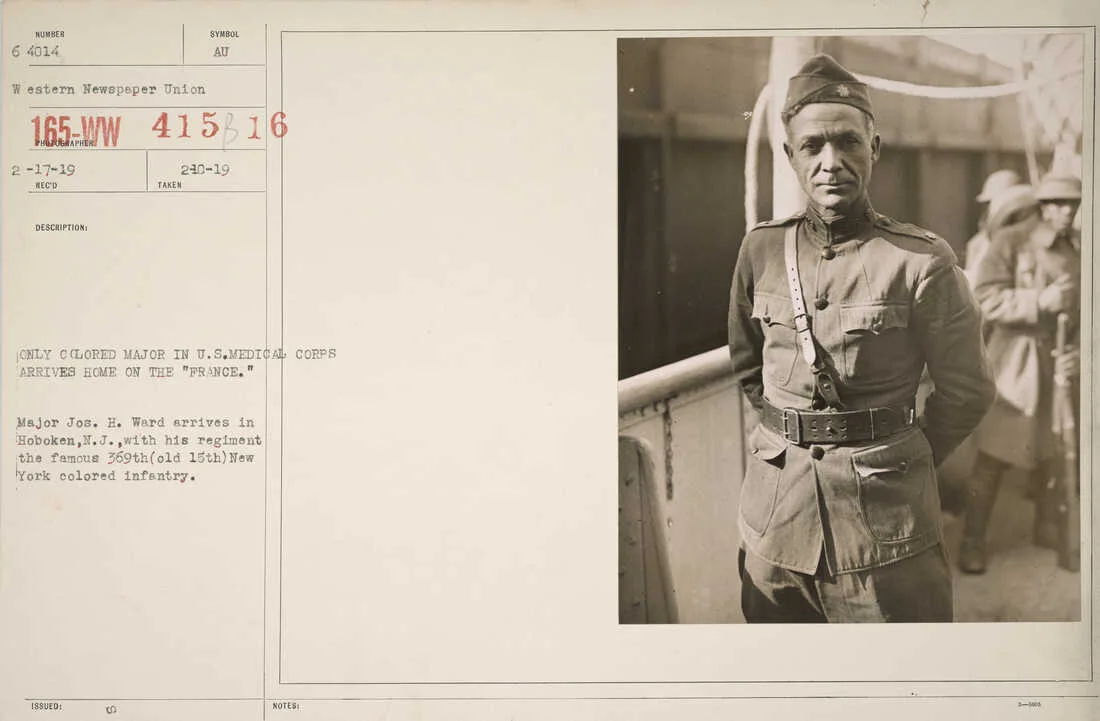

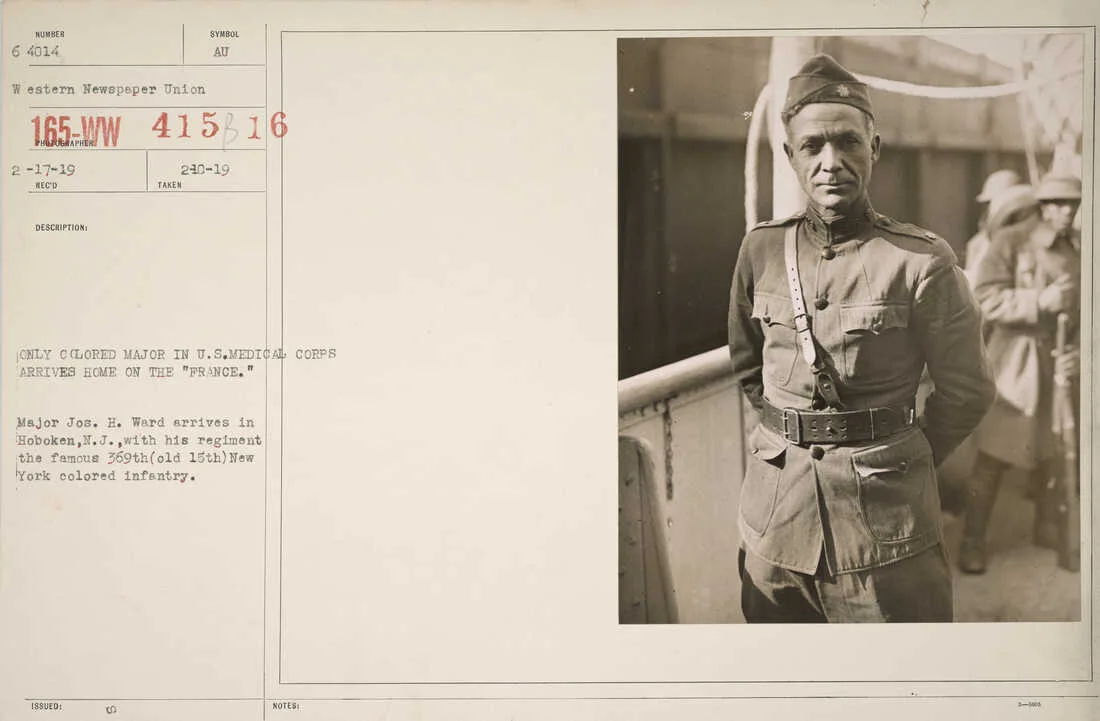

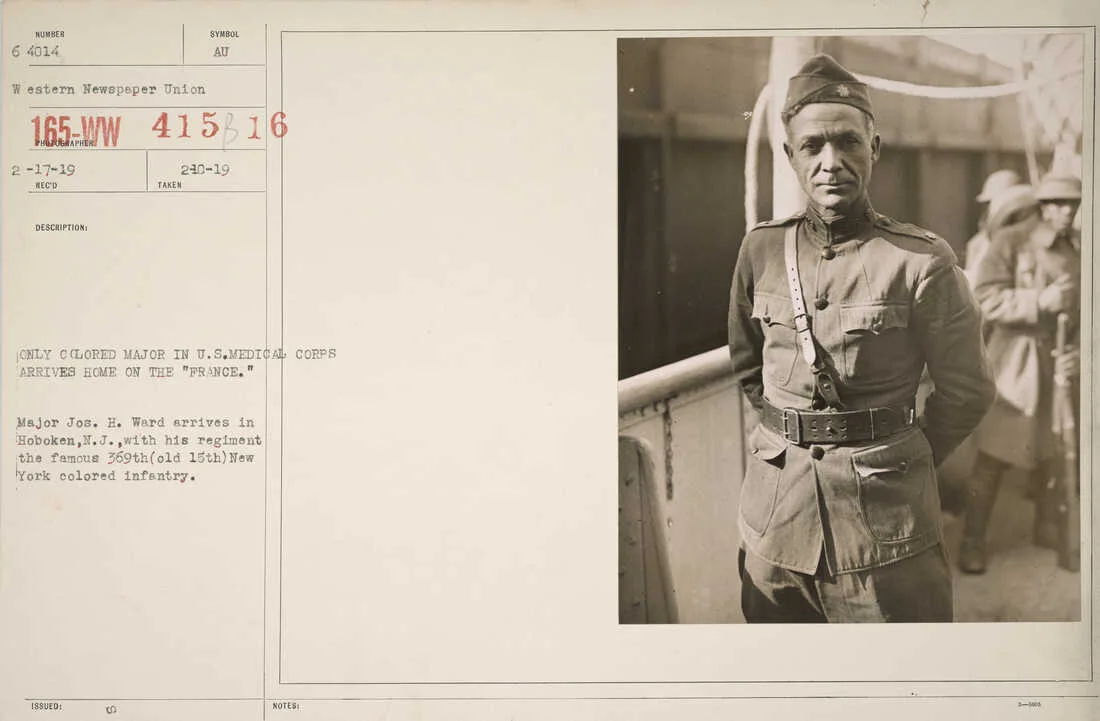

Dr. Joseph H. Ward was the first Black director of a VA hospital, after being commissioned as a major in the Medical Corps during WWI. He faced death threats and allegations of mismanagement from white supremacists.

National Archives

National Archives

The Ku Klux Klan marched on the campus that year.

“They did not want a Black-controlled hospital in the middle of Alabama.”

Initially, local officials prevailed and there was an all-white administration. But national pressure remained, and the federal government agreed to gradually hire Black doctors and nurses. A year later the Tuskegee VA was the first to be run by an all-Black medical team, led by Dr. Joseph Henry Ward, the first Black director in the history of the VA. And Esther Bullock was the first African-American chief nurse.

“This is a time where Black people fought for their health care,” Gamble says. “They stood up to the Klan. They stood up to the federal government.”

A victory against medical racism

Gamble says that’s a key takeaway because when many Americans hear Tuskegee, they think about a different healthcare story – when the federal government experimented on Black men in Tuskegee, leaving them untreated for syphilis.

“I think it’s important to tell these stories about African-Americans, where it’s not just about African-Americans being oppressed by the medical system, but African-Americans fighting against the racism in the medical system.”

A bird’s eye view of the sprawling Tuskegee VA campus. It spans more than 400 acres and includes more than two dozen buildings.

Tuskegee VA

Tuskegee VA

Amir Farooqi, director of the Central Alabama Veterans Healthcare System, says the Tuskegee campus is “where health equity for veterans began.”

Debbie Elliott/NPR

Debbie Elliott/NPR

It came at a high cost to those early leaders who faced death threats, and were accused of mismanagement. But Gamble says eventually, the Tuskegee VA became a hub for Black specialists to develop their careers. Members of the famed Tuskegee Airmen, the first Black pilots in the U.S. Army Air Corps, were treated there after WWII.

It’s long since integrated, and now serves all manner of veterans from across the region. The campus has also provided economic opportunity for African-Americans in the rural South.

Pharmacist Phillip Lyman has worked at the Tuskegee VA for 37 years, like his father before him. He’s proud of facility’s history.

Debbie Elliott/NPR

Debbie Elliott/NPR

Phillip Lyman has been a pharmacist at the Tuskegee VA for 37 years, continuing a family tradition.

“My father worked here for 42 years as the chief pharmacist, and my mom used to work at the canteen for 20 something years,” he says.

Lyman says for as long as he can remember, the VA was central to the Tuskegee community. It’s where he came to play Little League baseball and do Boy Scout activities. He takes pride in the history.

“There was no other place. This was the place. This was Mother Tuskegee,” he says, amazed that it has survived for 100 years.

As the campus celebrates its centennial, the National Park Service is evaluating the site for National Historic Landmark status.