In the American imagination, Soviet totalitarianism conjures thoughts of repression, violence and deprivation.

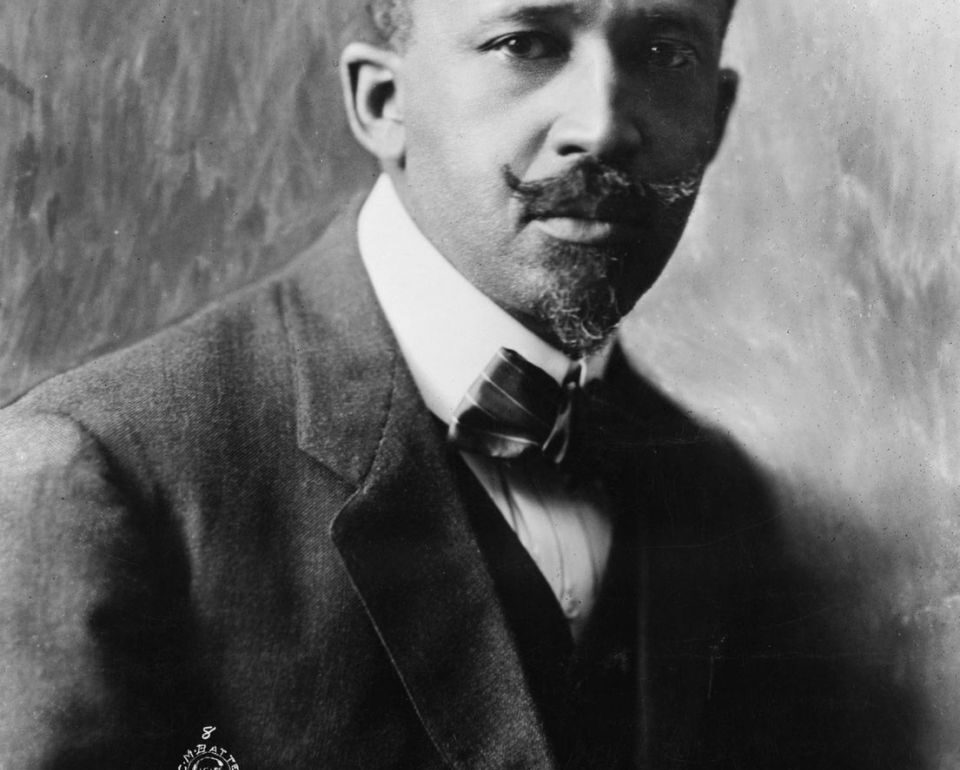

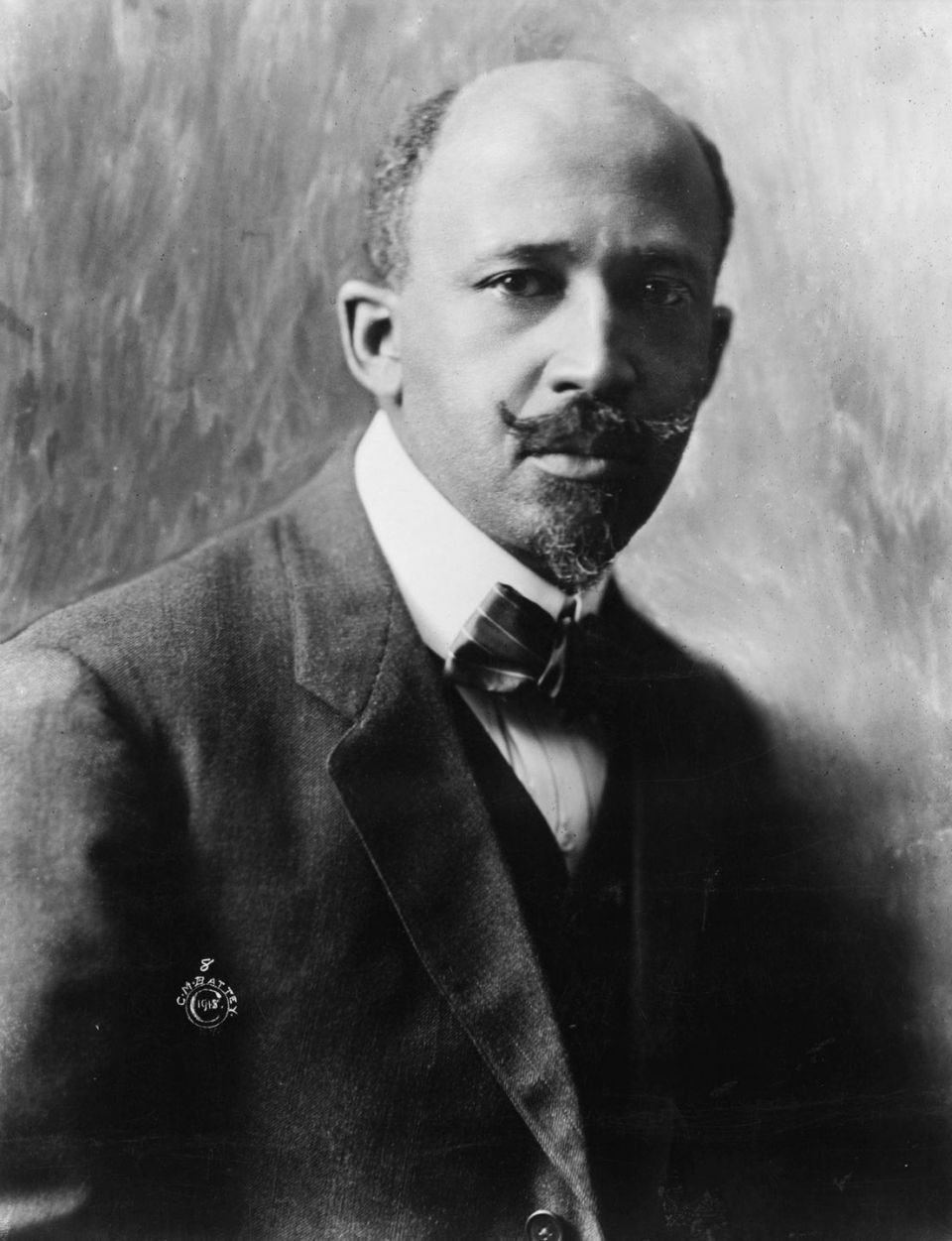

W.E.B. Du Bois is among African American writers whose Cold War views are explored in a new book by Stanford Assistant Professor Vaughn Rasberry. (Image credit: Cornelius Marion Battey / Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons)

During the Cold War, black writers and activists took a different view, challenging the United States to reconcile its message of liberty abroad while upholding Jim Crow laws at home.

This provocation lies at the heart of research by Vaughn Rasberry, assistant professor of English at Stanford, that tells the story of how African Americans challenged policy in the United States during the Cold War – with race at its core.

An intersection of two phenomena

Rasberry’s research focuses on the rise and fall of two 20th-century phenomena: the color line – domestically in the form of segregation and globally in the form of colonialism – and totalitarianism, including fascism, Japanese imperialism and communism.

Sifting through novels, essays, films, newspaper articles, propaganda and government documents, Rasberry examines how African Americans navigated the political waters of the mid-20th century living under segregation.

These findings appear in his book, Race and the Totalitarian Century: Geopolitics in the Black Literary Imagination, which highlights the cosmopolitan spirit African Americans had at the time and the commonality between struggles at home and those abroad.

Rasberry cites the Suez Canal crisis as a case in point. In 1956, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal Zone, wresting control from the British and French. This act of defiance against colonial powers became a flashpoint for African Americans, who saw their own struggle mirrored in Egypt’s resistance to colonialism.

“When you think about the sheer remoteness of this event, which had very little direct impact on African Americans, it says something that black America rallied behind Nasser,” Rasberry said. “There was a sense among people who were persecuted on the same basis that their fates were linked: a victory for Nasser was a victory for people of color worldwide.”

Racial progress of communism

During the McCarthy era, few Americans dared voice support for communism. W.E.B. Du Bois, one of the most prominent black intellectuals at the time, was a notable exception, siding with the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Shining a light on his later career, which most scholars have studiously avoided, Rasberry reveals uncomfortable truths about DuBois and the United States.

“Du Bois wrote a eulogy to [Soviet leader Joseph] Stalin in an unpublished manuscript, Russia and America, which valorized Soviet achievements. Why would he praise Stalin even after he was aware of the totality of Soviet violence and repression?” Rasberry asked. “My aim is not to uphold him, but to examine this period and see why he would hold these views at great personal risk.”

The key to understanding Du Bois’ puzzling support for Stalin may lie in the influence of his wife, Shirley Graham, who was staunchly pro-communist and well-connected with the political elite in Egypt, Ghana, China, the Soviet Union and Europe.

Du Bois also viewed the Soviet Union – despite the atrocities carried out against its own people under Stalin – as making considerable progress toward creating a society free of racial hierarchy, whereas the United States lagged. This progress resonated strongly with African Americans and people of color living in newly independent, formerly colonized countries.

“The writers in my book were able to see the value of the Soviet Union’s assault on racism,” Rasberry said. These writers leveled accusations of hypocrisy against the United States for presenting itself as a beacon of liberty while systematically oppressing African Americans.

A racially egalitarian world

Rasberry’s research harkens to his days as a graduate student when he became personally invested in the subject.

“I have had a longstanding interest in understanding how African American writers sought to create a more racially egalitarian world,” he said.

Stanford also played a role in shaping Rasberry’s argument. Over the five years it took to write the book, Rasberry taught undergraduate and graduate students on these subjects. “This teaching allowed me to test out these ideas to smart, skeptical students – 0to see what resonated and what needed to be refined,” he said.

The interdisciplinary nature of Stanford’s Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, where Rasberry is a faculty affiliate, provided an intellectual forum that enriched his thinking.

“These writers taught us that you cannot isolate the race problem in the United States from other struggles,” Rasberry said. “They also gave us another perspective on totalitarianism, which can help us to re-conceptualize this concept in more useful and politically salient terms.”