In February 2024, the International Criminal Court (ICC) delivered its long-awaited reparations order in the case of The Prosecutor vs. Dominic Ongwen. Nearly two decades after the ICC intervened in Northern Uganda, this milestone decision both acknowledges the suffering of survivors and underscores the complexities and limitations of international justice. For victims who have waited for justice for over two decades, the order has been bittersweet.

The Ongwen reparations order presents an opportunity to deliver redress through a survivor-centered and participatory process. At its core, such an approach emphasizes the meaningful participation of victims at every stage of the reparations process—from design and implementation to monitoring and evaluation. By leveraging survivor-centered and participatory methods, the process can better address the profound harm caused by Ongwen’s crimes while fostering healing and affirming victims’ agency and dignity.

The ICC convicted Dominic Ongwen, a former commander of the Lord’s Resistance Army, of 61 crimes in 2021—the highest number of convictions for an individual in the court’s history. These crimes include attacks on multiple internally displaced persons camps, sexual and gender-based crimes, and the conscription of child soldiers. Ongwen’s crimes inflicted severe physical, psychological, and material harm on victims and communities in Northern Uganda. His conviction and 25-year prison sentence, upheld in December 2022, paved the way for reparations for victims.

The Trial Chamber of the ICC (Trial Chamber) awarded reparations amounting to €52,429,000 to victims of Ongwen’s crimes. This is the largest sum ever awarded by the ICC, covering a total of 49,772 victims—a figure the court describes as a “conservative estimate.” The reparations awarded include collective community-based reparations valued at €15,000,000 and symbolic monetary awards of €750 per eligible victim, amounting to €37,329,000. They also included community satisfaction measures worth €100,000, which are dedicated to apologies, cultural ceremonies, and reconciliation initiatives.

In determining the type of harm, the court noted that direct victims of the attacks, victims of sexual and gender-based violence, children born of sexual crimes, and former child soldiers suffered severe and long-lasting physical, moral, and material harm. The indirect victims, who include family members and dependents, endured moral and material harm. Additionally, the entire victimized community experienced collective harm, while children of direct victims and those born from sexual and gender-based crimes suffered transgenerational harm.

Determining Ongwen to be indigent, the Trial Chamber urged the Trust Fund for Victims (TFV) to complement the reparations award to the extent possible and to undertake additional fundraising efforts as needed to fulfill the totality of the award.

The reparations order has sparked controversy. Victims have criticized the uniform symbolic monetary award for not adequately addressing the extensive and multidimensional harm they endured. At the same time, other critics have questioned the feasibility of implementing such a large reparations award, given the court’s limited resources.

The large scale of the reparations award reflects the exceptional nature of the case: Ongwen was convicted of the highest number of crimes in the court’s history, resulting in many eligible victims who suffered widespread harm. The award underscores the ICC’s recognition of the profound impact of Ongwen’s crimes while also exposing the limitations of the existing reparations framework.

Moving forward, bridging the divide between the court’s intent and victims’ expectations requires innovation, including adopting survivor-centered, participatory approaches to designing and implementing the reparations award to maximize its impact.

Recognizing the importance of a participatory process, the court ordered the TFV to conduct extensive consultations with victims, affected communities, and stakeholders to inform the design of the implementation plan. The court emphasized that the reparations process should respect survivors’ dignity, prevent re-traumatization, and consider cultural contexts. The TFV has subsequently conducted consultations in affected communities as it developed the implementation plan for the reparations order.

However, for the process to be truly participatory and inclusive, it must involve the most marginalized and disadvantaged victims—including survivors of sexual violence, children born of sexual violence, persons with war-related disabilities, and elderly victims. The process must also address victims’ unique needs, some of which are immediate, for example, by providing basic livelihood assistance and urgent physical and psychosocial rehabilitation. This interim support can empower survivors to participate meaningfully in the reparations process.

Further, the process should avoid exclusionary practices. Specifically, the prioritization criteria must not create a hierarchy of victims. For example, prioritization criteria that is based on whether victims participated in the trial is likely to cause tensions and conflict in the communities. Only less than 10 percent of the eligible victims (4,095) participated in the proceedings, due to limitations of the application process, including time constraints and staffing shortfalls in the ICC’s Victims Participation and Reparations Section.

A survivor-centered approach should involve victims and affected communities in determining which categories of victims deserve prioritization. By doing so, the reparations process gains legitimacy and local support ownership. For instance, ICTJ conducted a series of consultations with victims and other members of affected communities across Northern Uganda. In the consultations, participants identified and recommended persons in dire need who should be prioritized during the reparations process.

Providing legal assistance to victims is a critical part of a survivor-centered approach. Legal advice ensures victims are informed of their rights and have the tools to advance them. It also enables victims to fulfill the legal prerequisites for accessing reparations. For example, victims who do not have the official identification documents or letters of administration required to claim benefits on behalf of deceased relatives most often need legal aid to obtain these documents from the court or relevant government institution. Further, quality legal advice provides victims with timely information and careful explanations about every stage of the process. This includes information on the eligibility and prioritization criteria, the registration requirements, and the timelines.

The effectiveness of the reparations process depends on the availability of sufficient resources. The TFV, with its limited funds and competing obligations from other cases, faces significant challenges in meeting the reparations order’s demands. As of November 2024, states party to the Rome Statue have yet to contribute toward the implementation of the order. Contributions from member states, private donors, and international organizations are key to upholding victims’ rights.

The ICC’s reparations process is inherently limited because it only serves direct and indirect victims of Ongwen’s crimes. A significant number of victims of mass atrocities in Northern Uganda will not be eligible to benefit from the process. This is likely to cause discontent and tensions in affected communities. To close this justice gap, the Ugandan government must establish an administrative reparations program, as envisioned in the National Transitional Justice Policy. Such a program can complement the ICC’s process by addressing the broader socioeconomic needs of victims and affected communities and by facilitating community-level reconciliation.

The reparations order in the Ongwen case represents a significant step forward in acknowledging the suffering of victims and addressing the harm caused by widespread atrocities. However, it also exposes the limitations of international justice mechanisms in providing holistic redress. To give true value to the reparations order, the process must be victim-centered and participatory, with survivors’ voices and needs at the heart of the design, implementation, and monitoring process.

________

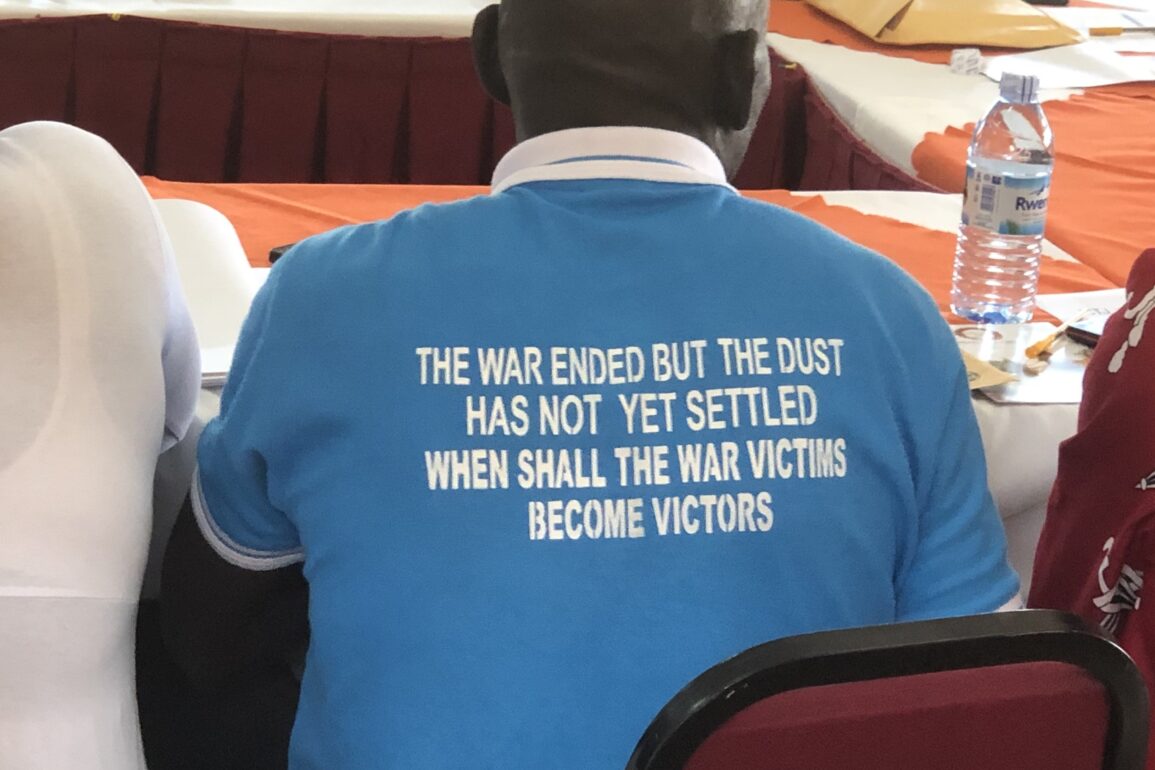

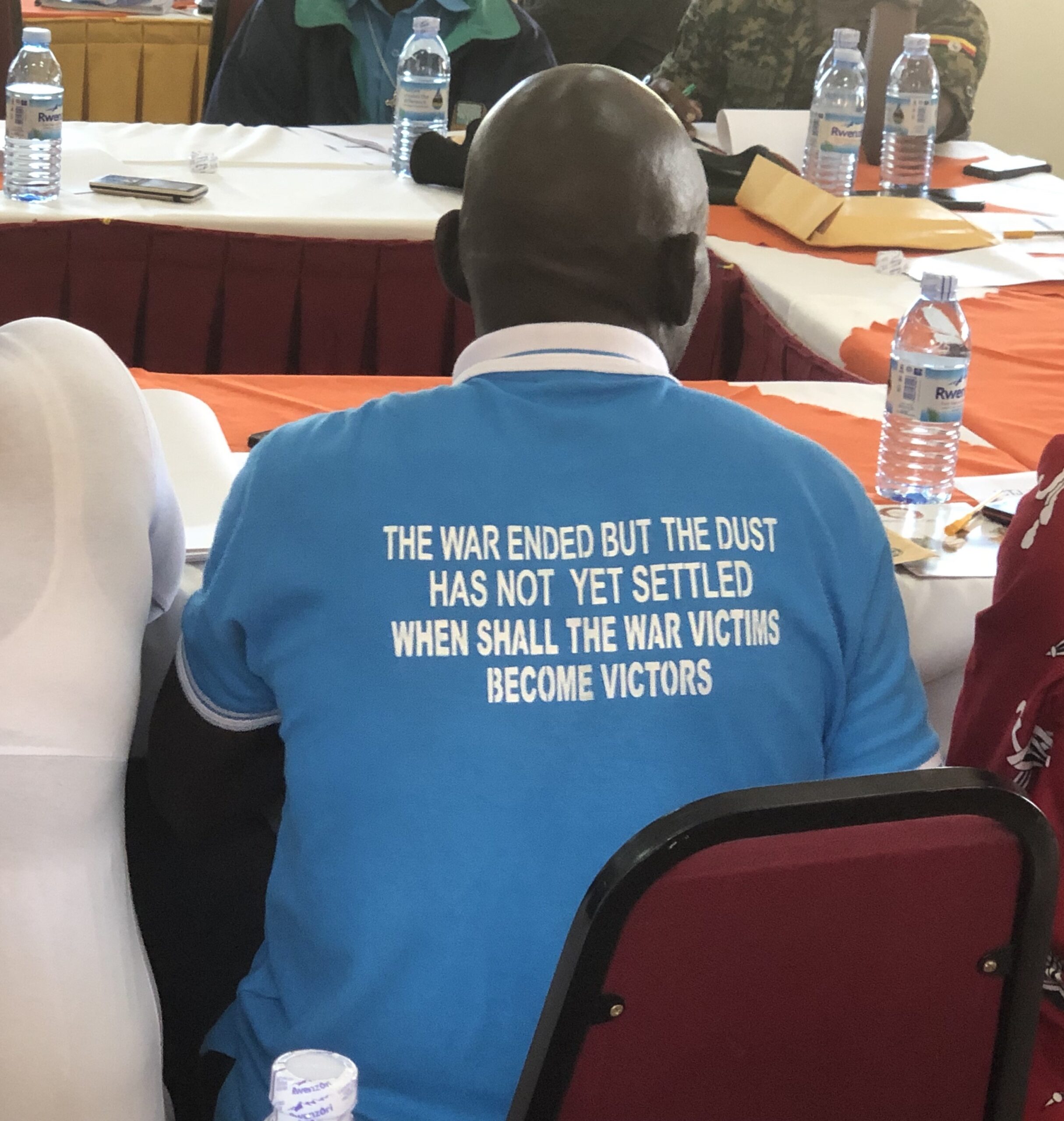

PHOTO: A member of West Nile Kony War Victims’ Association participates in an ICTJ-led validation meeting of the human rights documentation project in Arua district, West Nile sub-region, Northern Uganda in July 2019. (Sarah Kasande/ICTJ)