The notion that Britain, being a former European colonial power, owes reparations to those it formerly enslaved and colonised has now reached the top of government. At the recent Commonwealth summit in Samoa, it was agreed that the “time has come” for a conversation on reparatory justice, a joint statement the UK reluctantly also signed. It is the culmination of a campaign that dates to at least the early days of postcolonial theory. “Colonialism and imperialism have not settled their debt to us once they have withdrawn from our territories,” Frantz Fanon wrote in his 1961 book The Wretched of the Earth. “The wealth of the imperialist nations is also our wealth. Europe is literally the creation of the third world.”

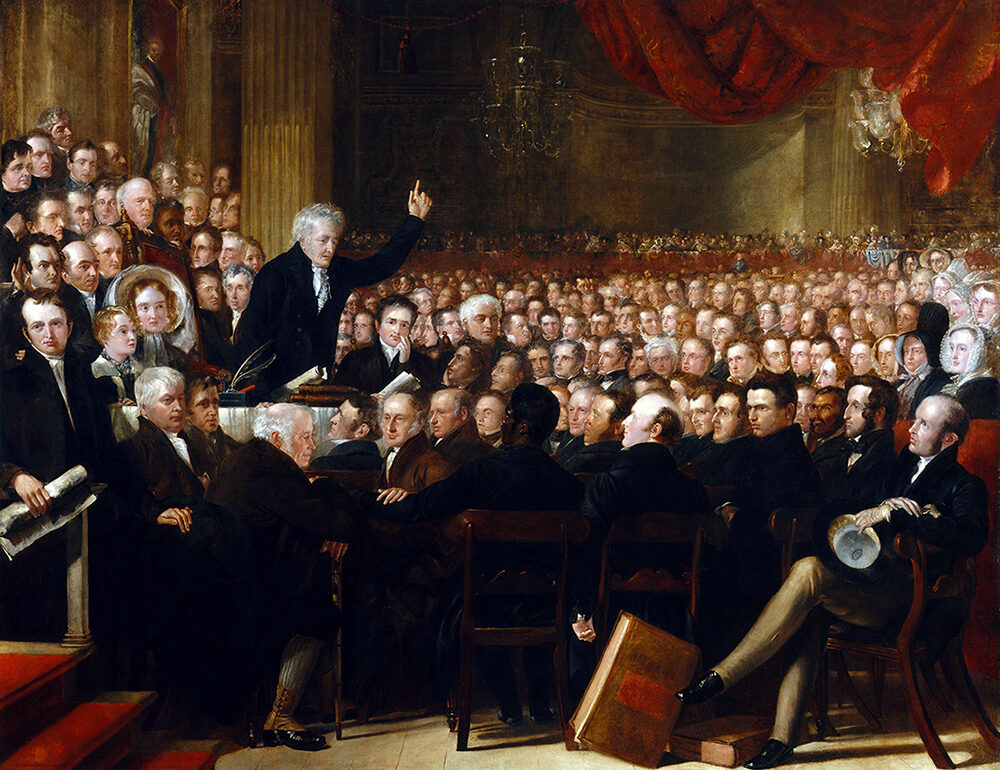

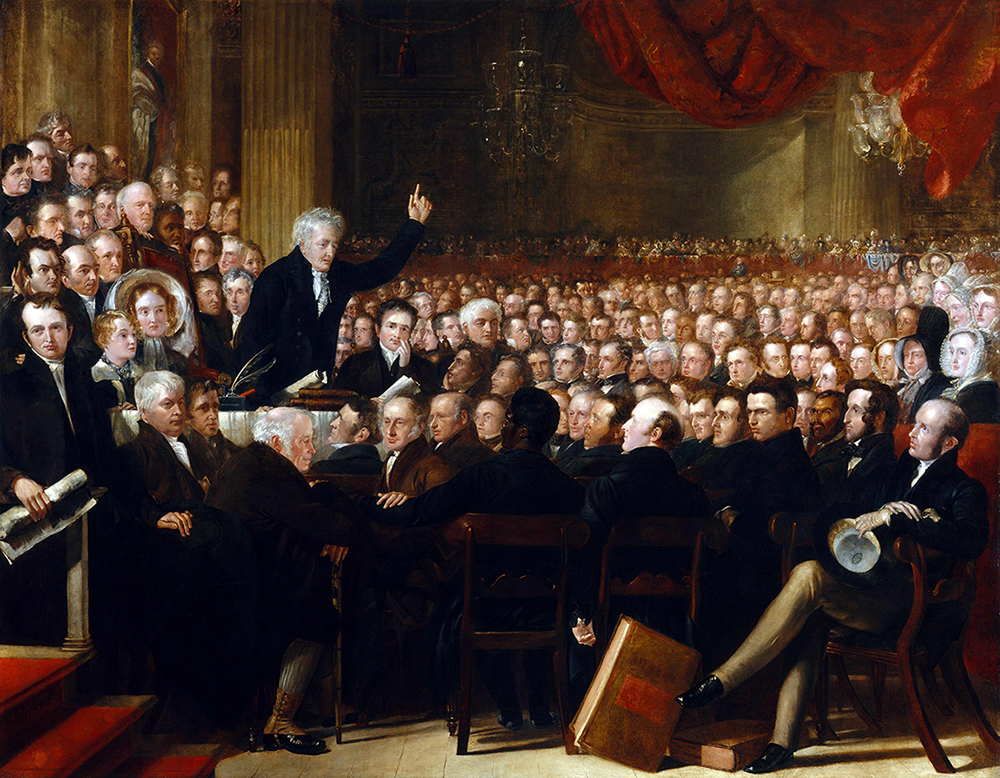

Slavery has existed throughout most of human history across virtually every society and culture. But the Atlantic slave trade between the 15th and 19th centuries was distinct. It was inextricably tied into the unrelenting colonisation of the Americas by Europeans and the development of the modern understanding of “race”. Millions of Africans were purchased and trafficked as human cargo across the hellish Middle Passage to meet the demand for cheap labour, working the plantations in the European colonies to produce commodities like sugar cane and tobacco.

The slave trade made plantation owners wealthy, producing a wealth that they then brought back home to Britain. They invested it in estates, warehouses, churches, artworks, ports, banks and in the new factories that were being built during the Industrial Revolution. Many British institutions and organisations can trace some kind of link back to the slave trade, as various historical investigations have demonstrated. Being a beneficiary from hyper-exploited black slave labour, one of the most prominent pro-reparations campaigners, Hilary Beckles, argues Britain has a “black debt” that is owed.

Pro-reparations campaigners can point to a small number of precedents that a larger reparations programme could follow from. In 2021, Germany officially recognised and apologised for the genocides committed against the Herero and Nama peoples by the Kaiserreich, and agreed to pay $1.3 billion to the Namibian state through existing aid programmes (though it was worded delicately to avoid the word “reparations”). Britain itself has officially apologised and given reparations to the Kenyans it tortured during the Mau Mau revolt in the 1950s. If apology and compensation was possible in these cases then why not for Atlantic slavery and colonialism?

It is important to take into account that there are some bad faith arguments against reparations. There are the usual cheap appeals to whataboutery. What about the Trans-Saharan slave trade: if Britain must pay reparations for slavery then does that mean all historical crimes must also recompensated? An easy reply to this is just because one can’t make good for all the great crimes of history doesn’t mean that one can’t try to and confront some of them. Then there was Robert Jenrick’s absurd suggestion that the former colonies should be grateful for the “inheritance” the British empire left for them. Too often these modes of argument are based off of a churlish mixture of self-pity and nationalist resentment, as well as the pricking of a bad conscience.

What’s particularly interesting about the argument for reparations is its psychological and moralistic dimensions. Beyond its historical basis, it also mobilises race as the primary basis of political identity. It holds that black people are suffering from an intergenerational inequality and a trauma of selfhood from the after-effects of slavery and colonialism that must be healed. Criticising Keir Starmer’s rejection of reparations, for instance, Diane Abbott said: “Real reparations aren’t just about compensation, they’re a way of tackling colonialism’s damaging legacy of racism and inequality. They are about the total system change and repair needed to heal, empower and restore dignity.”

Despite the pseudo-radical rhetoric, this numinous framing obscures the problem of contemporary social inequality, a multifaceted reality rooted in political economy and class that can’t be easily reduced to racial categories. In any case, the predicament of the black working class in 2024 is the result of 40 years of neoliberalism, not four hundred years of slavery and colonialism. Reparations are no panacea. The reality of reparations if they were put in practice is, to paraphrase Oscar Wilde’s radical critique of charity, that the remedies would “not cure the disease: they merely prolong it. Indeed, their remedies are part of the disease.” It would just be another capitalist instrument to manage inequality, exploitation and poverty within and between nations, instead of transforming society in such a way as to eliminate it.

Morally, the call for reparations rests on the need for “justice”. Crimes of the past need to be made right – and this is something long overdue. But this notion of justice has a backward-looking perspective that, to borrow from Walter Benjamin, is more concerned with “avenging enslaved ancestors” than with “liberating future grandchildren”. And it is in stark contrast with a younger Frantz Fanon, who powerfully and movingly expressed opposition to reparations in favour of a radical freedom that is future-oriented in the conclusion of his first book, Black Skin White Masks, in 1954:

“I have neither the right nor the duty to claim reparations for the domestication of my ancestors… Am I going to ask the contemporary white man to answer for the slave ships of the 17th century? I do not have the right to be mired in what the past has determined… I am not the slave to the slavery that dehumanised my ancestors… There is no Negro mission; there is no white burden… I as a man of colour want only this: that the enslavement of man by man cease forever.”

Fanon and other black radicals like CLR James and Kwame Nkrumah were against reparations because they still reflect the relationship of paternalism and dependency that defined the colonial relationship. But more crucially, they enchain black people to the scars of the past, where their identity and subjectivity must forever be determined by slavery and colonialism, with no hope of transcending it. Against this historical determinism, they put their faith in freedom, and the exciting undetermined possibilities of the future. In this sense, Keir Starmer was actually more right than he knew in his initial remarks before the Commonwealth summit: that we must “look forward” rather than have “very long endless discussions about reparations on the past”.