Surely Keir Starmer could be more conciliatory on reparations for slavery (Starmer says he wants to ‘look forward’ and not talk about slavery reparations, 23 October), taking a lead from Justin Welby, who at least apologised for the Anglican Church’s role (Archbishop of Canterbury reveals ancestral links to slavery, 22 October). The slow escape from post-emancipation poverty that the UK could help alleviate with simple, inexpensive, long-term measures is what Caribbean prime ministers are drawing to people’s attention.

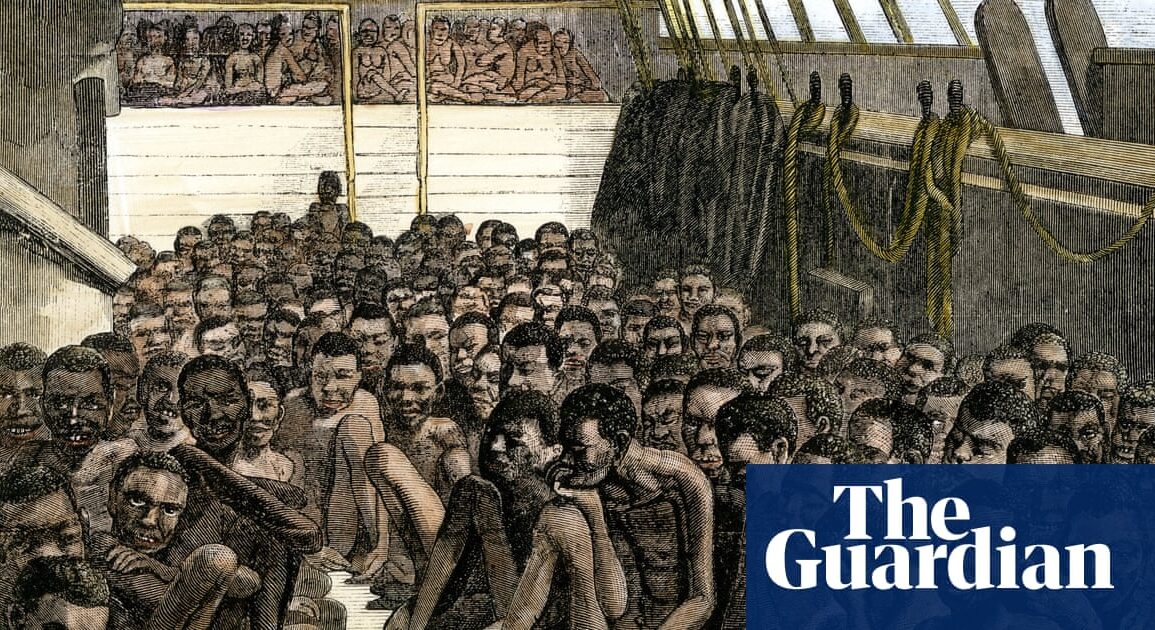

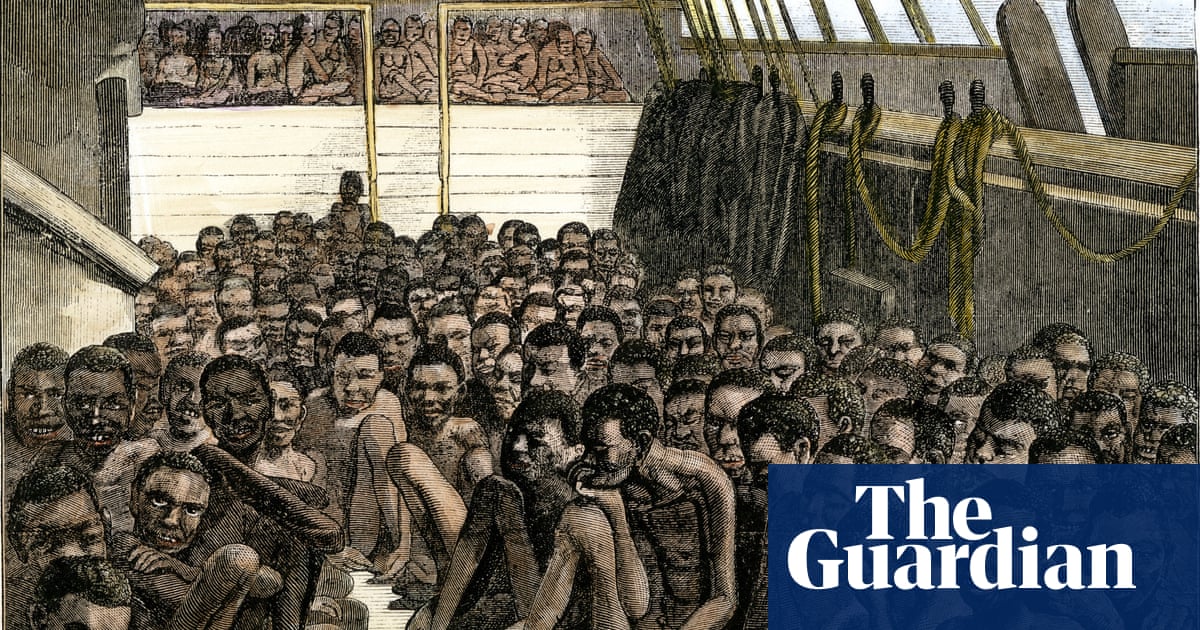

Our local Labour party passed our motion on the topic, but this was sadly not deemed a conference priority by the constituency. The British public fail to realise how much empire wealth still current in Britain came from the 200 years or more of British kidnap-trading of Africans, transatlantic humiliation, torture and forced labour that slavery was. Its lasting legacy, as the Windrush saga showed, is the ongoing racism endured by Britain’s black and mixed-ethnicity population.

Kennedy Cruickshank Visiting professor, University of the West Indies, Alison Rooper Documentary producer, David Blagbrough Retired, British Council

Frederick Mitchell, the Bahamas foreign minister, has expressed surprise that a Labour government is continuing the Conservatives’ policy of refusing to discuss an apology or reparations for British colonial exploitation, including the slave trade (Analysis, 24 October).

But that is not the only continuity between Keir Starmer’s line and that of the Tories on this issue. When Starmer told the BBC that we “can’t change our history” (Report, 24 October), he was repeating the trope that Gavin Williamson used when he defended the decision in 2021 by Oriel College, Oxford, not to remove a statue of Cecil Rhodes: “we should learn from our past, rather than censoring history”.

Of course we can’t change what happened in the past. But we can change history. An apology would open a new chapter, calling for a real commitment to redressing the atrocities and crimes of that past. Reparation must be both material and symbolic, stepping decisively away from the pernicious narratives that imperial history fostered, justifying and glorifying empire.

Chris Sinha

Cringleford, Norfolk

Hilary Beckles’ position on reparations and apologies for slavery relies on a myth of nationhood that conceives of the nation state as a metaphysical personality that can carry guilt and responsibility across the ages quite apart from the individual human beings who constitute it (Global calls for reparations are only growing louder. Why is Britain still digging in its heels?, 24 October). Slavery was a crime (one of history’s worst) that ended 200 years ago. Guilt is not something that can be inherited.

To hold the people of Britain today responsible for what their distant ancestors did is absurd. Even more so when you consider that migration means the composition of a country is very fluid, and that at the time of slavery only a tiny proportion of men (and no women) in Britain had any political representation or other responsibility for the crime.

Rich countries such as Britain should, as a matter of international justice, be contributing much more to the development of poorer countries, but apologies today cannot atone for crimes committed in the remote past by others and to others with whom those making the apology have no moral relationship.

Stephen Smith

Glasgow

Perhaps it is those whose families benefited from the government’s generous compensation to enslavers when slavery was abolished who should now pay reparations?

Mary Brown

Stroud, Gloucester

So the prime minister has adopted a stance only to look forward, rather than looking backwards.In a previous job, Keir Starmer was director of public prosecutions. That role involved upholding the rule of law by looking at alleged past wrongs, prosecuting those responsible, and seeking reparations.

As prime minister, he has chosen to ignore past acknowledged crimes against humanity of British slavery, and legitimate claims for reparations. Through this stance of choosing only to look forward, Starmer consigns upholding the rule of law, prosecuting past wrongs and claims for reparations to the whitewashed dustbin of history.

Mike Fitzgerald

Amsterdam, the Netherlands

While the argument Nels Abbey makes in favour of reparations (Why white working-class Britons should fight to secure colonial slavery reparations, 28 October) – in which he rightly raises not only the evils of slavery but also the exploitation of the white working class in colonial and industrial expansion – has much to commend it, the danger in calling for reparations lies in how the political right will respond.

Reparations will not be presented as the payment by those still benefiting from past oppression and exploitation to “level the playing field” for the future of those whose ancestors had their lives and prospects blighted by the greed of others, but rather as a tax that the white working class will have to pay to black people for things done centuries ago, if left-of-centre governments are voted in. Divide and rule, even at the expense of truth and colossal societal upheaval, is too much part of the right’s playbook for them to ignore.

Keir Starmer may be right to dodge the bullet of reparations. The word is now too firmly fixed in the public mind as a repayment for slavery. Rebuilding is perhaps a better concept. Rebuilding can include populations, institutions, constitutions and organisations; it can be for everyone, irrespective of colour, allowing all those who need help to receive it, from a system of taxation that includes attention to historical inequities and anachronistic advantage, but which does not risk pitting one set of the exploited against another, polarising debate to the extremes, and fettering progressive political change.

Ryk James

Penhow, Newport