(Reuters) -After California state legislators passed bills addressing the legacy of slavery and racial discrimination, Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed the most ambitious of the reparations proposals.

The setback last month followed turmoil at Harvard over that elite university’s plans to make amends for historic ties to slavery and a lawsuit challenging an Illinois city’s reparations payments. But advocates say they are undeterred.

Shortly before the California legislative session ended this summer, a state Senate reparations bill on land restitution proposed by state Sen. Steven Bradford passed 56-0. But the Black Caucus blocked votes on two other proposals in that package — one creating a fund and the third an agency to determine who would be eligible for reparations.

“It’s a shame,” Bradford said. “To be this close to the finish line, and not at least have a vote.”

The Black Caucus blocked the bills because the proposed agency, not the legislature, would have had oversight, members wrote on X.

Governor Gavin Newsom said when he vetoed the land restitution bill that it could not be implemented without Bradford’s other proposals. Newsom signed legislation the Black Caucus had made separately, including measures banning discrimination based on natural hairstyles.

Bradford, a Black Democrat, finished his last term in office this past session. But California Assemblywoman Lori Wilson said reparations initiatives will be brought up during the next legislative session.

“The setbacks have actually re-invigorated people in the reparations movement,” said Kamilah Moore, a lawyer and former chair of the California Reparations Task Force, which released a 2021 report documenting California’s role in perpetuating slavery and racial inequalities. A handful of its over 100 policy suggestions were turned into bills.

“Reparations is ultimately a federal responsibility that states and municipalities have taken into their own hands,” Moore said. “Hopefully it’s a domino effect that leads to national reckoning.”

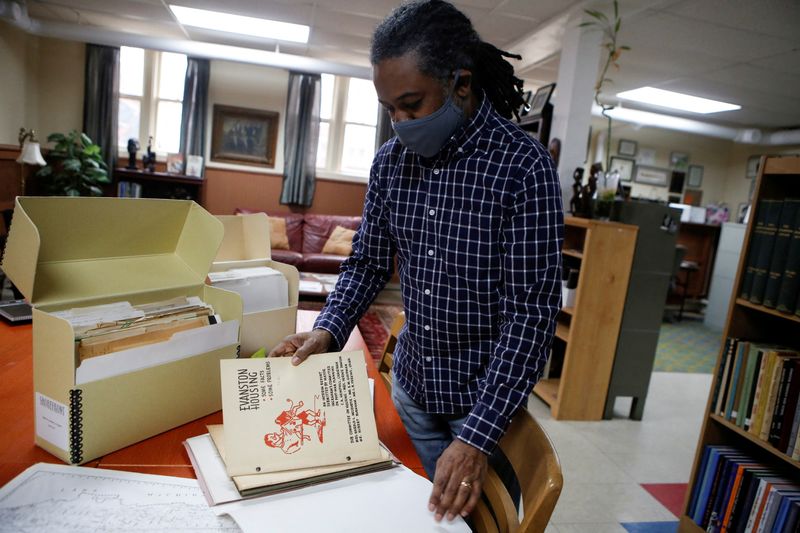

In Evanston, Illinois, city council member Bobby Burns said Evanston was not discouraged by a recent lawsuit from the conservative group Judicial Watch, which called restitution efforts “discrimination.”

“The lawsuit hasn’t stopped us from continuing to make good on the commitments we’ve made,” Burns said.

While at Harvard, after an executive with its initiative to address the legacy of slavery stepped down amid staff complaints questioning the university’s commitment, a spokesperson said it took the concerns seriously and would reach out to descendants of enslaved people.

A Reuters/Ipsos survey last year showed that 74% of Black Americans support reparations, compared to 26% of white Americans. Common concerns include addressing persistent racial disparities in the labor market, education and health, along with the cost of the initiatives and questions about whether today’s taxpayers should pay for past wrongs.

Immediately after the Civil War reparations efforts for the newly freed were abandoned as white Southerners reasserted authority through racial segregation laws and violence.

At the federal level, a proposal to create a commission to study what reparations might look like has been stalled in Congress for 35 years. Lawmakers in California are among those who have provided leadership on the issue, particularly amid demonstrations calling for racial equity following the 2020 murder of a Black man, George Floyd, by a white Minneapolis police officer.