On August 27, African faith, farming, and environmental leaders came together to launch an unusual statement. Their open letter was addressed to “the Gates Foundation and other funders of industrial agriculture.” It charged these funders with promoting a type of corporate, industrial agriculture that does not respect African ecosystems or agricultural traditions.

The letter was organized by the Southern African Faith Communities’ Environment Institute (SAFCEI), and has over 150 signatories. Its release was timed to influence the Africa Food Systems Forum in Kigali, which starts today. Partners of this conference include the Rwandan government, AGRA, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and other philanthropies, agribusiness companies, and aid organizations.

The open letter takes particular aim at two linked organizations. The Gates Foundation is primarily known for its public health investments, but has also made major inroads into agriculture. In Africa much of this work extends through the Nairobi-based AGRA (previously known as the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa). The Gates Foundation is a cofounder and the largest donor to AGRA. Other large donors include the UK and US governments.

Under a basket of policies dubbed the “green revolution,” AGRA, the Gates Foundation, and likeminded institutions have sought to substantially increase the use of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and commercial seeds in Africa. This has centered on developing new seeds and a network of sellers. The aim has been to dramatically increase agricultural output, in order to reduce hunger and elevate farmer incomes.

But by AGRA’s own admission, it failed in its goal to double crop yields and incomes for 30 million farmers by 2020. In fact, some critics argue, AGRA has made things worse.

According to an external assessment by Timothy A. Wise of Tufts University, severe hunger in AGRA countries increased by 30% between AGRA’s founding and 2018. Crop yield increases have been modest, and where they exist, they haven’t always been enough to cover the higher cost of farming with commercial seeds and agricultural inputs. Dependence on fertilizer has increased the debt and financial precarity of the small farmers who make up the majority of farmers in Africa. In some cases the limited yield increases have also been temporary, as soil fertility has diminished due to monoculture farming and fertilizer use. For instance, Ethiopian farmers “will say that the soil is corrupted, meaning it cannot produce food” without synthetic fertilizer, reports Million Belay of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA).

There have been knock-on effects, Belay says. For instance, Zambian farmers who have become indebted, due to synthetic fertilizer purchases, have had less money for food and their children’s education.

In other words, many farmers’ families are poorer and hungrier than before, while the land itself is less productive.

While AGRA hasn’t managed to double farmer income and yields, it has succeeded in shifting government policies for the worse, according to Belay. These include the dilution of regional biosafety regulations and fertilizer regulations, Belay says. In Kenya, farmers can now face prison time for saving or sharing seeds.

A new AFSA briefing note states that AGRA is seeking to place consultants within government offices and “directly crafting policies at the continental, national, and local levels.” This includes a new 10-year policy for agricultural investment in Zambia.

All, in all, it’s a highly commercialized, elite, and often rich-world vision of African agriculture. Tim Schwab writes in The Bill Gates Problem: Reckoning with the Myth of the Good Billionaire, “Rarely, however, do the targets of Gates’s goodwill, the global poor or smallholder farmers, have a seat at the table. In the case of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, or AGRA, the allies include a bevy of corporate partners: Syngenta, Bayer (Monsanto), Corteva Agriscience, John Deere, Nestlé, and even Microsoft.” AGRA has been criticized for aiding its agricultural partners to expand in Africa.

When it comes to harmful agricultural models, AFSA’s Belay acknowledges that the Gates Foundation is not solely responsible. “We cannot blame everything on Gates,” he says. He points more broadly to the narrative propagated in wealthy countries that food cannot be produced without agrochemicals, novel seeds, and market agriculture, despite the severe effects on the land and the limited effects on reducing hunger. “That’s a powerful narrative, and they have fashioned African universities in this image,” Belay argues. He also points to African governments’ spending on green-revolution approaches.

One reason this industrial-agriculture narrative has taken hold is that it seems intuitive that producing more food equals feeding more people. This myth is both persistent and dangerous. The world has more than enough food for everyone. Hunger persists because of poverty and inequality, compounded by conflict and climate change.

To give just one current example, Victoria Tanimonure of Obafemi Awolowo University’s Department of Agricultural Economics says that parts of Nigeria experiencing hunger are exporting food to neighboring countries. This pattern has also been seen in previous famines, such as exports of potatoes to the UK during the Irish Potato Famine.

Thus, it’s not underproduction that’s the problem, and technical solutions alone are insufficient—no matter how loudly agribusinesses proclaim that their products are essential to feeding the planet.

The tremendous power of the Gates Foundation

A larger criticism is about the Gates Foundation’s enormous amount of power. Schwab writes, “In this deeply unbalanced, one-sided discourse, there has been little room for serious public debate and little recognition around what the foundation is actually doing. Bill Gates is not simply donating money to fight disease and improve education and agriculture. He’s using his vast wealth to acquire political influence, to remake the world according to his narrow worldview.”

Schwab also criticizes the major influence the foundation now holds over journalism on international development, including agriculture in low- and middle-income countries. He believes that the foundation’s extensive grant-making and journalist-training have contributed to a monopolizing of conversations and a reluctance to hold this powerful organization to account. (I have received funding from the Gates Foundation, through programs administered by the United Nations Foundation, European Journalism Centre, and Solutions Journalism Network.)

The foundation has dramatically reshaped global health and development, often for the better. Yet it should not be immune to criticism. As Mariam Mayet, of the African Centre for Biodiversity, told Schwab in The Bill Gates Problem, the Gates Foundation has mobilized so much funding and influence for an industrial model of agriculture, that it has crowded out alternatives. “Another future could not be born because of the Gates’s agenda and what it funded and stood in the way of—whatever transformation and transition that may have been possible, that could have resulted in less social exclusion, less inequities, less poverty, less marginalization of already vulnerable communities,” Mayet said.

An alternative type of agriculture often touted by environmentalists is agroecology, a holistic approach to agriculture seeking to steward ecological health as well as local control. In practice this can often include minimizing synthetic fertilizers and prioritizing soil health.

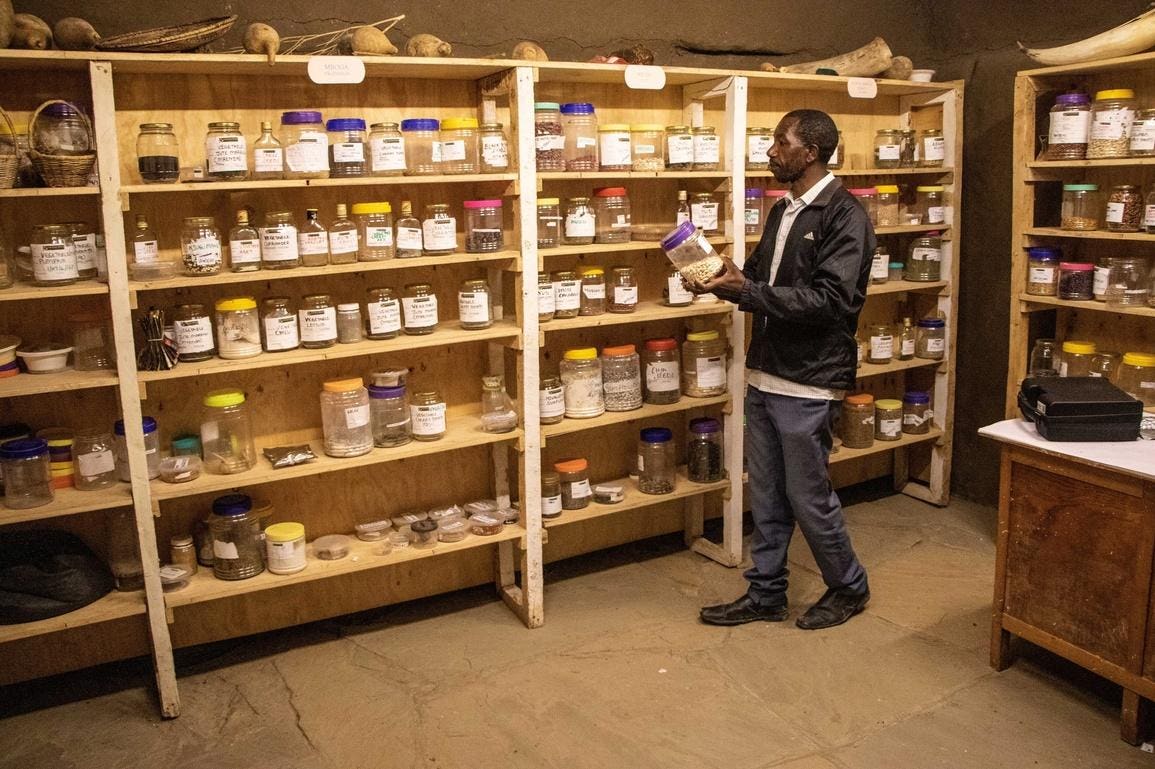

Belay gives specific examples of successful non-industrial agriculture, like a Kamapala training center where young farmers exchange information about making biofertilizers themselves, rather than turning to expensive and soil-acidifying products. The nutrient-rich natural ingredients can include cow urine or discarded bones. Individually, these programs may be small-scale compared to the market reach of multinational agribusinesses. But “there are so many methods,” Belay stresses.

What reparations might look like

Enock Chikava, Director of Agricultural Delivery Systems at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, states, “We believe African farmers deserve and should have access to a range of affordable agricultural tools and innovations that can help them adapt to stressful conditions that continue to intensify due to climate change. Our support of many organizations like AGRA helps countries prioritize, coordinate, and effectively implement their national agricultural development strategies, based on country plans, to achieve this goal. We also believe that engaging in open dialogue with a diversity of African voices – including farmers themselves – is critical to our work and will continue to seek out constructive dialogues to address food and nutrition security around shared goals and the best ways to achieve them.”

AGRA did not respond to a request for comment. AGRA maintains that its work with local small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is beneficial for seed diversity. The organization reports that it has supported 2.7 million smallholder farmers to adopt improved soil health practices, including through organic and inorganic fertilizers and drought-resistant seed varieties. It reports key quantitative achievements in terms of additional investments and economic value mobilized through partnerships (US$ 141 million), seeds sold (123,000 metric tons), and SMEs supported (9,000).

But these kinds of market figures are not the types most compelling to those calling for reparations. The signatories to the open letter addressed to the Gates Foundation and others haven’t specified the details of the reparations they’re seeking. What they’re seeking extends beyond a dollar amount. In a press conference on August 28 about the open letter, the word “dignity” came up often.

One of those calling for a restoration of dignity through the food system was Bishop Takalani Mufamadi, of SAFCEI. “It’s not just monetary, it’s holistic—because we are looking at restoring the dignity of the people,” Mufamadi said. He called not just for a change in investments and financial support, but also retraining of farmers and restoration of damaged land. “The reality and the challenge is that these pesticides are destroying not only the land, but the water table,” he commented.

Mufamadi called AGRA, the Gates Foundation, and seed and agriculture companies “false prophets of food security. They claim to be messiahs of the hungry and the poor, but they have failed dismally to deliver because of the industrialization approach, which degrades soils, destroys biodiversity, and places corporate profit over people. It is immoral, it is sinful and unjust.”