Listen

Next month, a federal trial will take place in Galveston that will mark the first serious test of the Voting Rights Act since the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a key portion of the law in June. The case could have implications not only for redistricting in Galveston County but across Texas and around the country.

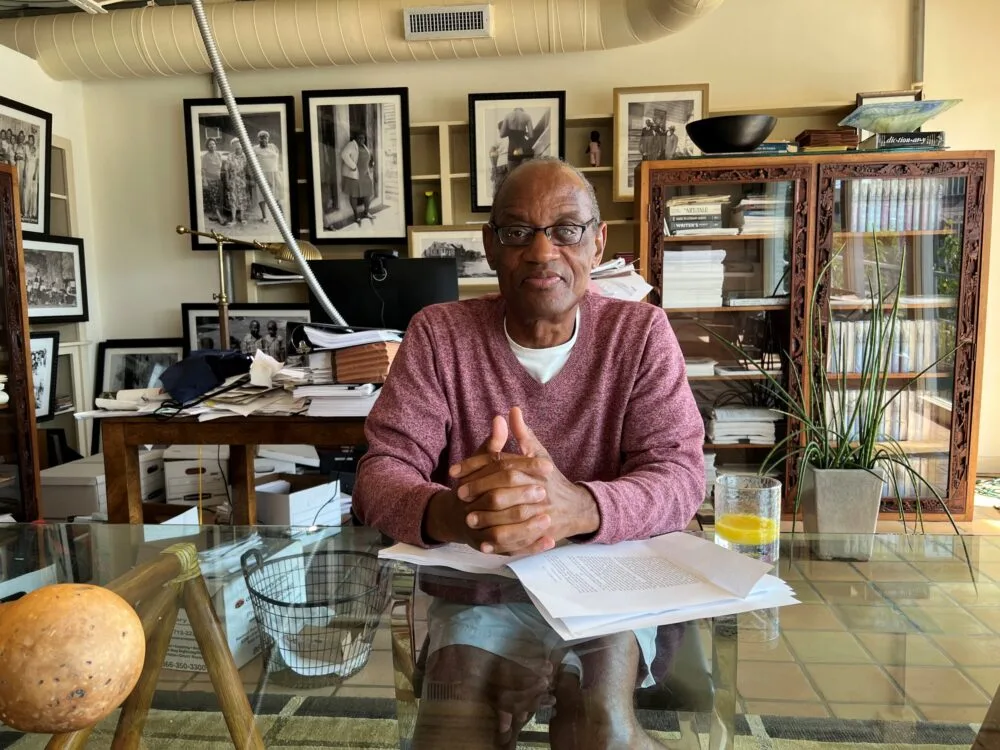

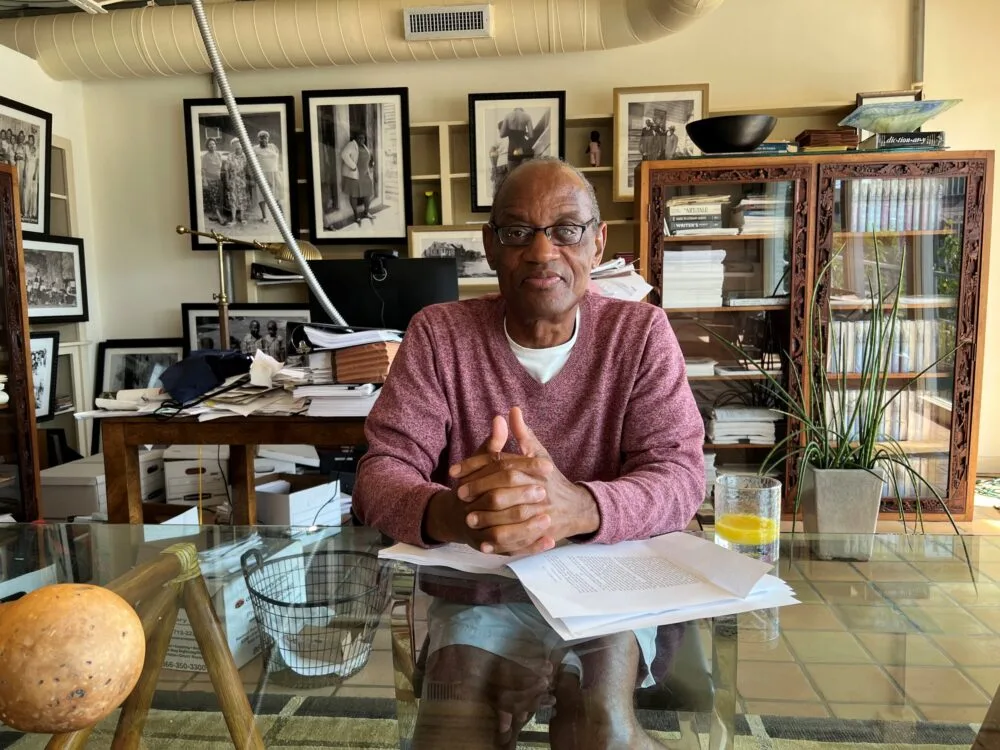

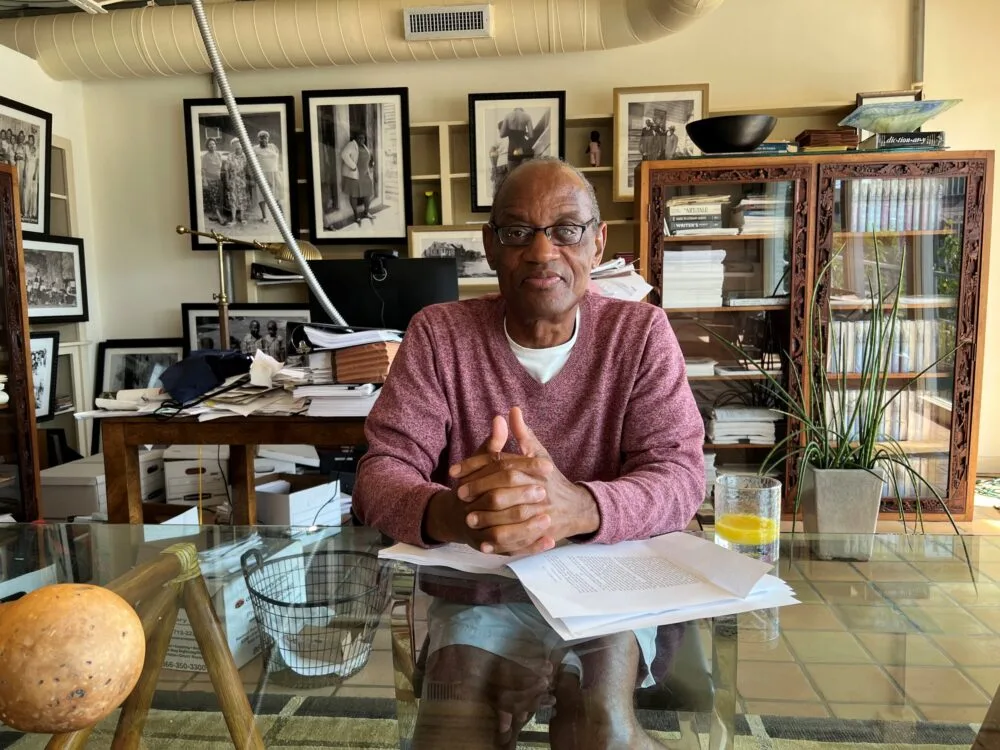

The making of a civil rights attorney

Anthony P. Griffin grew up in Baytown during the Jim Crow era. “I used to joke that I could never get lost in any part of Texas, because all I had to do was go into the wrong neighborhood, and the cops will come and ask me where am I going,” Griffin said.

Griffin said he continued to face open and more subtle racial discrimination all through high school. Even though he made straight As, his guidance counselor – like him, African American – tried to get Griffin to drop his advanced courses and switch to shop classes to prepare him for a career in woodworking or welding.

But Griffin was determined to become an attorney. He earned his law degree at the University of Houston and began practicing civil and criminal law in Galveston in the late 1970s. He did extremely well. Too well, for some of the county’s leading white legal figures, whom he said led an effort to deprive Griffin of his license to practice law.

“I spent a career of shots being taken against me, but…the first shot was taken in terms of holding a disbarment (over) my head for seven years, and the State Bar (had) to admit it’s the longest disbarment that they ever had at that time. Never took my deposition. The allegations were sufficient enough. because it was about discrediting me,” Griffin said.

“I spent a lot of money and a lot of time trying to change how we elected the officeholders in Galveston County,” he said.

By the time Griffin retired from law practice in 2014, he had spent nearly three decades bringing voting rights cases against the city and county of Galveston, often successfully.

Shelby County and Galveston County

But the year before Griffin retired brought a dramatic change in the way voting rights were enforced in the United States. In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which required many southern states to get permission from the federal government before changing their election laws, in a decision known as Shelby County versus Holder.

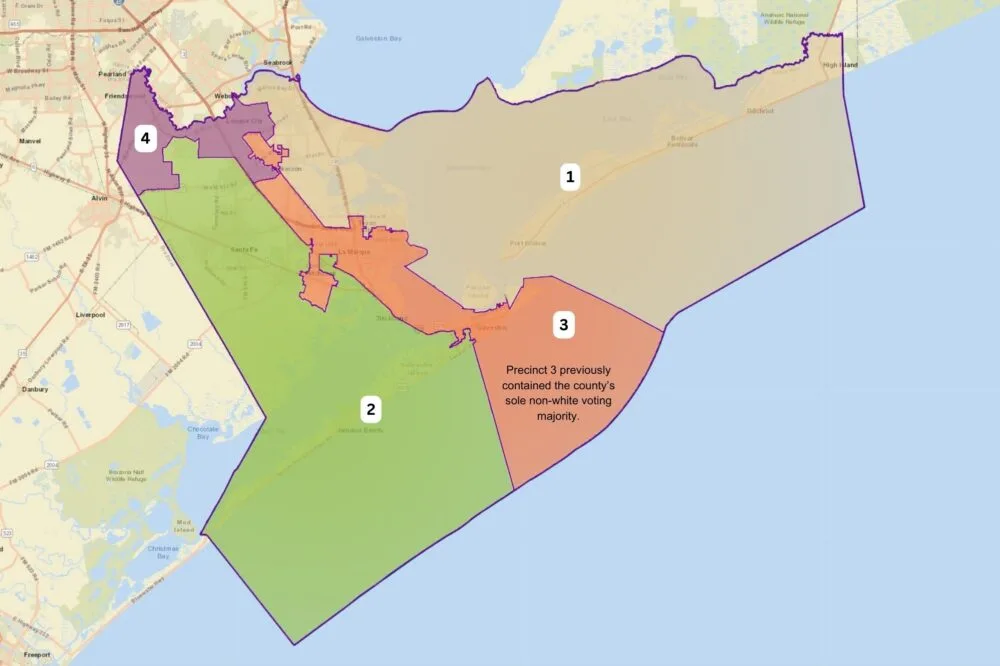

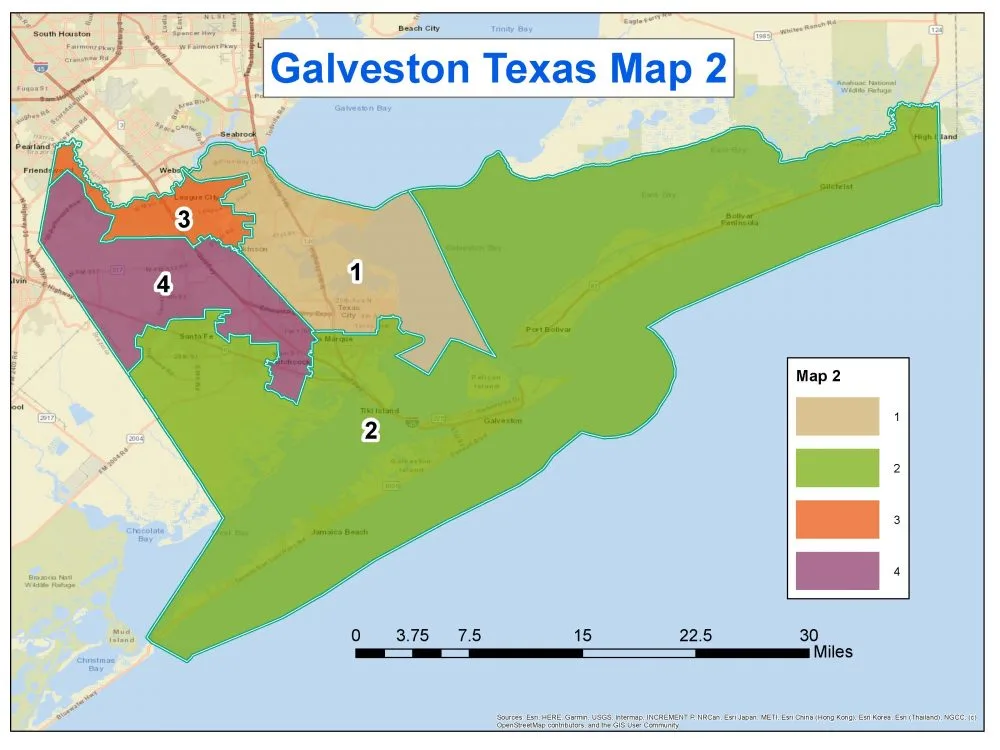

When the Republican-led Galveston County Commissioners Court redrew its map in 2021 to eliminate the sole precinct represented by a non-white Democrat, Commissioner Stephen Holmes, Griffin says it felt all too familiar.

“It’s been sad to watch how Texas has done everything you can to exclude people. And voting has been one of those primary mechanisms by which control has been asserted,” Griffin said.

Lucille McGaskey, a longtime community activist based in Texas City, explained what the map change meant. “The original Precinct 3 has been carved into four different precincts,” McGaskey said. “And I thought basically that it was illegal for you to do that, to break it up like that, because you took away our voting strength.”

It’s a practice known as “cracking.” Even though Galveston County is now more than 40% Black and Latino, people of color no longer make up the majority of a single precinct, so Stephen Holmes stands to lose his seat when he runs for reelection next year.

Holmes is no longer the only African American member of the Galveston County Commissioners Court. In 2022, County Judge Mark Henry appointed Republican Robin Armstrong to fill out the term of the late Commissioner Ken Clark. Armstrong won a term in his own right last November.

“(Armstrong) grew up in this area,” McGaskey said. “He grew up probably three blocks down from my mom’s house. But he lives in another district. He lives in (Precinct) 4, and he represents that (largely white and Republican) group up there…and I think they just figured, ‘We’ll just replace the Black with another Black.’ But that’s not the same thing.”

The GOP majority had good reason to think they’d be able to make the new map stick.

“Galveston County was actually one of the first local jurisdictions to attempt to enact a discriminatory map after Shelby County came down in 2013,” said Valencia Richardson, a staff attorney with the Campaign Legal Center.

Richardson is representing current and former county officeholders challenging the new map. Two other cases, including one filed by the Biden administration, have been consolidated with hers as Petteway versus Galveston County.

Milligan and its implications for local governments

Richardson says a new Supreme Court decision, handed down in June, gives her confidence. Allen versus Milligan held that the state of Alabama violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by racially discriminating when redrawing its congressional maps. Just because local jurisdictions no longer need federal permission to redraw maps, that doesn’t mean they can racially discriminate.

“Milligan affirmed the last 40 years of legal precedent is correct, and that it should be applied,” Richardson said. “It puts a little wind on our backs to have Milligan affirm 40 years of precedent and particularly for our Section 2 case, because what our clients allege in the Section 2 case is very similar to what the plaintiffs in Alabama allege.”

None of the attorneys representing Galveston County’s case would comment publicly on the upcoming trial, but their public filings argue its map reflects partisan gerrymandering, which the Supreme Court has allowed, and not racial gerrymandering.

“They’re going to have a hard defense after the Allen versus Milligan case,” said Charles “Rocky” Rhodes, who teaches constitutional law at South Texas College of Law Houston. “I think they were really hoping that the Supreme Court was going to cut back on the protections of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. And the Supreme Court rejected some of the defenses that I think that they would otherwise have used.”

Rhodes said while the Milligan case dealt with congressional districts, it could be used in the Petteway case to show racial gerrymandering on the county level as well. Sarah Xiyi Chen agrees. Chen is an attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project. She represents a collection of NAACP chapters, as well as the local chapter of LULAC, in a case that’s also been consolidated with the Petteway case.

“Galveston County is not the only place where people do not have the opportunity to elect the candidate of their choice in their local government,” Chen said. “We’re talking about school boards, city councils, county commissioners (affecting) the daily lives of Texans and people all across the country.”

The trial is set to begin in Galveston on August 7. It’s expected to run for two and a half weeks. Chen is hoping that means it will be decided far enough in advance to give Stephen Holmes a fair shot at holding onto his commissioner’s post in 2024.

“If we win the suit, we will request the drawing of a fair map that does respect the Black and Latino communities, those communities of interest that have been represented in county government for several decades under the map that was then destroyed in 2021,” Chen said.