The search to better understand his roots took Paul Thomas Harper to his late grandmother’s attic in St. Paul, Minnesota. There, among the letters and photographs, he found clues that, once plugged into a genealogy website, helped him trace his family tree back to his fourth great-grandfather.

His name, Harper would learn, was Swansey Adams. Born into chattel slavery in Virginia in 1796, Adams was eventually taken to Illinois, where his enslavers forced him to toil in the salt mines near downstate Shawneetown and, later, in the lead mines around Galena before he gained his freedom.

The revelation of his ancestor’s enslavement and indentured servitude startled Harper, a military veteran and social worker, in part because he, like many others, incorrectly assumed that Illinois, the home of Abraham Lincoln, had been a so-called free state leading up to the Civil War.

“I’m tired that American history is not being told as it should be,” Harper, 57, said. “I want for people to hear and understand what Swansey Adams went through.”

Harper’s family story is one of many being documented by the Illinois African Descent-Citizens Reparations Commission, a state panel tasked with a sweeping mandate that includes the eventual creation of a comprehensive report for state lawmakers on the feasibility of reparations for Illinois’ descendants of chattel slavery.

Illinois was the second state to create such a commission, born out of legislation passed in 2021 amid a national racial reckoning following the police killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor in Louisville.

But its existence has been somewhat overshadowed by similar efforts elsewhere. Since the commission’s official formation on Jan. 1, 2022, its output has largely centered on educating the public about the commission and on orchestrating a study on possible reasons for reparations. That study began last month and is projected to take more than a year to complete.

The pace has frustrated some observers, particularly in light of last year’s U.S. Supreme Court decision to effectively end affirmative action in college admissions, a conservative group’s federal lawsuit this May against Evanston’s groundbreaking reparations program and a Springfield-area police officer’s fatal shooting of Sonya Massey last month.

“I think it needs urgency because it’s an emergency,” said Karl Brinson, NAACP Chicago Westside Branch president. “It’s not being treated the way it should be treated. Each day that goes by, people get disheartened. They get apathetic.”

The commission’s ambitious to-do list extends beyond reparations to include recommendations on neighborhood stabilization, vocational training centers and a “slavery-era disclosure bill.”

And yet, its progress on an inherently arduous set of tasks has been further slowed as commissioners struggle to attend meetings in person amid competing personal and professional demands (with the expiration of COVID exceptions, virtual attendance does not count toward being present, per state law).

Those absences have been exacerbated by lengthy delays in filling commission seats, a persistent problem in state government. Until two months ago, seven of the 18 commissioner spots were vacant.

As such, a Chicago Tribune review of records found, the commission has failed to reach a quorum in a little over a third of its meetings since its first in December 2022, causing delays in votes on key issues.

“You would hope they’d be further along,” said La Kisha Latham, a spokesperson and board member of the nonprofit Conrad Worrill Community Reparations Commission, which has pushed for reparations in Chicago. “And so, the fact that they’re just now having hearings, from the community’s perspective, it may seem disappointing and concerning. Even so, we know that things take time and we look forward to collaborating and contributing to the mutual cause of reparations.”

Still, despite stiff headwinds, the commission has started to gather momentum.

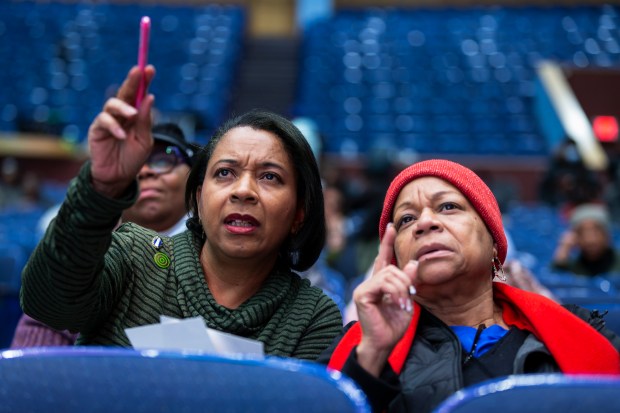

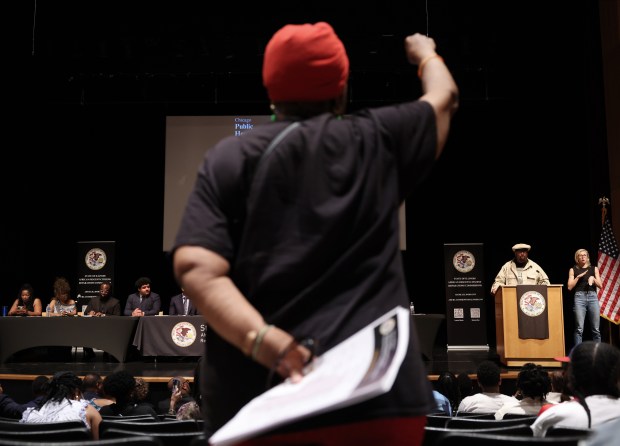

More than 300 people filled the auditorium at Englewood’s Kennedy-King College on a Saturday morning in July for the commission’s first public hearing, which featured presentations and speeches (Harper being one of the speakers) on the topics of enslavement, racial terror and political disenfranchisement.

Eight other hearings are planned across the state; the next two are scheduled for Saturday in East. St. Louis and Oct. 19 in Springfield.

Also in July, at the behest of the commission, a research team from the University of Illinois Chicago Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy started work on a study of harms done to generations of the state’s Black residents — a study commissioners anticipate will help lay the foundation for their reparations recommendations.

“I believe that the commission is working actively to move as fast as we can … making sure we understand what exactly is asked of us, so we can propose things that are both efficient and practical for the state,” said commission Chairman Marvin Slaughter Jr., a University of Chicago researcher and reparations scholar.

“That might take a little bit longer than some people may have hoped. But also, when it comes to the reparations space, we’ve been demanding reparations since emancipation in 1865. As one of the younger members of the reparations space nationally, I’m OK with moving a little bit slower and making sure that we get it right and being able to bring along the community.”

‘We know the nation that we live in’

Smaller reparations programs across Chicagoland are experiencing mixed results as well.

Considered the first attempt by a U.S. city to pay reparations to its Black residents, Evanston’s reparations program approaches its fourth year of existence with its future uncertain after the conservative group Judicial Watch filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of six plaintiffs who argue the program is race-based and violates the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause.

The lawsuit names as plaintiffs six people whose relatives lived in Evanston during what that city’s reparations program has identified as a 50-year period of housing discrimination that often deprived Black residents of building wealth through homeownership and kept them segregated to a tiny enclave on the city’s western edge.

Three groups were eligible to receive benefits: ancestors who were Evanston residents and at least 18 years old from 1919 to 1969, direct descendants of those ancestors and any current residents who can show they were victims of racially discriminative housing post-1969.

None of the plaintiffs in the suit identify as Black, according to lawsuit documents.

Each disbursement of $25,000 was initially permitted to be used one of three ways: On a down payment for a new home, on mortgage payments, or on home repairs. Evanston was forced to expand on that framework when two of the first 16 selected recipients, siblings Kenneth and Shelia Wideman, told the city they couldn’t use the money for housing.

Both in their 70s, the Widemans said they wanted to stay in their respective rental apartments. They previously told the Tribune that homeownership would be a burden, the payments insufficient for them or their children to purchase a home in Evanston’s expensive real estate market.

From there, Evanston’s Reparations Committee began exploring the possibility of direct cash payments to recipients. It took some time to ensure those on welfare programs wouldn’t be negatively impacted by the funding but solutions were found.

Once allowed in early 2023, direct cash payments quickly became the most popular disbursement method.

Judicial Watch President Tom Fitton previously told the Tribune that Evanston’s program is “just a proxy for giving out money to people based on race.”

“It looks to me like Evanston wants to be on the cutting edge,” Fitton said. “We don’t want those anti-discrimination protections to be upended through these types of programs. It’s important this be corrected as soon as possible so other states, localities and the federal government don’t go down this path of doling out tax money to individuals simply based on race.”

Evanston filed a motion last month to dismiss the federal lawsuit, arguing in part that the plaintiffs lack standing to sue. Plaintiffs have until Aug. 19 to respond.

Chair of Evanston’s Reparations Committee Robin Rue Simmons told supporters following the lawsuit filing that the city would not waver in its support of the program.

“This lawsuit is not a surprise,” she said. “We know the nation that we live in. This is from outside our community and we have been preparing to fight it. We have a legal framework and much support that will allow us to move forward with confidence.”

She went on to call the lawsuit an attack on all communities engaging in the hard work of reparations.

Al Tillery, a Northwestern professor of political science and director of the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy, called the claims in the lawsuit nonsense.

Tillery accused the plaintiffs’ organization of being “centered in a political movement that aims to reestablish a racialized caste system in America.”

“Anyone that knows the history and understands how our legal system has traditionally functioned should know that these claims are as founded as saying that the world is flat,” he said.

Still, he worries Evanston could lose, pointing to the existence of conservative judges in all levels of the judicial system.

Evanston’s program issued its first round of disbursements in 2022. According to data presented at the May 2 meeting, the program has paid more than $4.8 million to 193 recipients across the ancestor and descendant categories. All those in the ancestor group have been contacted, and the city has begun disbursing payments to descendants with the expectation of handling about 80 recipients per year.

Updated data will be available in September when the committee begins meeting again.

Funding for the program has been gathered from the city’s recreational cannabis sales tax and portions of taxes accrued from the real estate transfer tax.

‘We didn’t want to wait’

Just west of Chicago in Oak Park, village officials have considered embarking on a reparations program. A citizen-led task force began in fall 2021 from a protest group called Walk the Walk in response to Floyd’s murder.

“We didn’t want to wait for the village to move forward,” former task force member Christian Harris said. “There were things we could do as far as studying the history that could be done.”

The task force submitted its report to the Oak Park Village Board in February but wasn’t able to present the findings until the July 16 Village Board meeting.

The board spent a fair chunk of its discussion on the Evanston lawsuit, something Harris said the task force specifically tailored its report to avoid.

Harris said he was “profoundly disappointed” by the board’s reaction, arguing the board has been considering its own role in the reparations movement for years.

Trustee Susan Buchannan echoed Harris’ sentiments, saying the apology the task force included as part of its requests of the village was long overdue.

Another trustee, Brian Shaw, said the village can’t go another year without taking steps forward.

Harris called for an apology before the board in February 2023 when it appeared split on whether the issue should be tackled at the local or federal level. Some at the time pointed to the federal bill sponsored by Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas, who died July 19. t

The task force gave a number of recommendations to the board beyond the official apology. They included partnerships with financial institutions to provide low-interest down payment assistance programs to Black residents, an allocation of 50% of the village’s Inclusionary Zoning Fund to create a restorative justice fund, and the purchase of the Percy Julian family home to allow his daughter Faith to remain in the property for as long as she likes and then repurpose the property into a community center.

Chemist Percy Julian pushed past racial barriers — amid attacks on his Oak Park home

Taxes on new apartment buildings in Oak Park are deposited in that zoning fund. The village requires all such buildings to allocate 10% of units for affordable housing, but owners can bypass that requirement by paying the tax equal to $100,000 per unit.

Proceeds from the zoning fund, which officials said currently is near $2 million, are used to help people who are homeless or at risk of becoming so.

Harris is doubtful anything will come of the report.

“Oak Park is a wonderful place in the sense that it’s always willing to have the conversation … but that’s where it starts and ends 99% of the time,” Harris said.

In Chicago: $500K, a task force and an apology

Chicago’s dormant reparations discussion received a boost two days before Juneteenth, when Mayor Brandon Johnson issued an executive order that created a task force to study the issue.

Aided by $500,000 in the 2024 budget, the task force will examine “all policies that have harmed Black Chicagoans from the slavery era to present day” and recommend remedies. Those policies could cover housing, policing, health, education and mass incarceration, among others.

The task force has 12 months from its first meeting to produce a public report on its findings.

Johnson’s executive order also included a formal apology on behalf of Chicago “for the historical wrongs committed against Black Chicagoans and their ancestors who have and continue to bear injustices.”

Latham’s nonprofit, the Conrad Worrill Community Reparations Commission, is hoping to work with the city as a consultant to the new task force, she said. Established in 2020, the nonprofit has spread the word about reparations and engaged with city officials to get the movement going.

The commission is hosting a reparations rally Aug. 19, alongside the first day of the Democratic National Convention, beginning at 5 p.m. at the Dr. Conrad Worrill Track and Field Center.

“We could not pass the opportunity to gather national leaders and local leaders and the different organizations here for the rally during the DNC,” Latham said.

Invited speakers at the rally include the ADCRC’s Slaughter, Latham, Rue Simmons, the main architect behind Evanston’s reparations program, and others. Tickets for the event can be ordered online.

‘Stolen labor of our ancestors’

At the state level, two more commissioners have been appointed in the last two months, dropping the total vacant seats to five. Slaughter, the commission chair, said part of the issue has been finding candidates from outside Cook County.

Another persistent issue, the lack of public awareness, could be rectified when it brings on a public relations firm. Commissioners had discussed such a move as far back as March 2023, at the first meeting of the public engagement subcommittee (and the fourth overall meeting of the ADCRC). But, as is often the case with government bureaucracy, the hiring process has been slow. The state is still finalizing a request for proposals, Slaughter said, which should be released by the fall.

Asked when he hoped the firm could get started, he answered with a laugh, “yesterday.”

“It is really something that we would love to have as soon as possible because it does lift a burden,” Slaughter said.

With a public relations firm in place, Slaughter said the commission could focus more of its attention to what he and others informally call the “harms report” being compiled with the help of university researchers.

Before they can identify what reparations should entail and who should receive them — two undoubtedly thorny questions — the commission and its research partners aim to document centuries of past harms inflicted on Illinois’ Black residents and draw a connection to present inequities.

Among the focus areas is the state’s first constitution that allowed for the enslavement and indefinite indentured servitude of people like Harper’s fourth great-grandfather, Swansey Adams — a “brand of slavery,” said Kennedy-King College associate professor Daniel Davis during the July 19 public hearing, “just as brutal as the more well-known Southern version.”

Then there were the state’s draconian “Black Codes” that preceded the Civil War, which included among their punitive measures a ban on gatherings of three or more Black people.

The early 20th century saw acts of racial violence and terror against Black residents in Springfield (1908, a catalyst for the creation of the NAACP), East St. Louis (1917) and Chicago (1919).

The research would also examine subsequent decades of denied opportunities in housing, education and employment that, along with overpolicing and mass incarceration, have driven racial disparities in health and carved a wealth chasm between Illinois’ Black and white residents.

“Our wealth situation in this country is a direct result of the stolen labor of our ancestors,” said Kamm Howard, a longtime reparations advocate and founder of the nonprofit Reparations United.

‘How long has this conversation been taking place?’

Some have criticized the state commission for spending time and resources researching seemingly well-trodden ground.

“How long has this conversation been taking place?” asked Brinson, the NAACP Chicago Westside Branch president. “You’ve got studies with cobwebs and dust on them.”

Others questioned whether similarly exhaustive studies were required before the U.S. government paid out billions of dollars to Native American tribes and Japanese Americans incarcerated in internment camps during World War II.

A few of the 31 people who spoke publicly during the ADCRC’s July hearing used their allotted two minutes to slam Chicago and the state for not waiting for a lengthy study to spend millions to address the recent influx of migrant arrivals, comments that drew spatters of angry agreement across the assembled crowd of roughly 300.

But Gabby Green, policy and program manager with the Chicago-based nonprofit, BlackRoots Alliance, said the research is essential.

“You and I both know that slavery existed and there have been multiple forms of systematic anti-Blackness since then,” she said. “But for any government entity, they need more direct evidence. It’s important to know our history so we can mend those historical wounds and really be able to thrive in a community.”

Slaughter is well-aware of the extensive research on the topic, having co-authored a 2022 report with noted reparations scholars William Darity Jr. and A. Kirsten Mullen entitled, “The Cumulative Costs of Racism and the Bill for Black Reparations.”

And yet, he said, questions remain. “There still have to be more models that are built that explain to us if we were to do, hypothetically, cash payments to close the racial wealth gap, how long would it take for that gap to open again unless you have additional supports?”

Slaughter said he expects the research team to finish its report by the end of next year. That report, he added, should also help the commission make progress toward its other mandates, which include recommendations on the preservation of Black neighborhoods in the state, the building of a “Vocational Training Center for People of African Descent-Citizens,” and the creation of an “Illinois Slavery Era Disclosure Bill.”

A handful of cities and states — including Illinois and Chicago — have similar legislation that requires some or all companies bidding on government contracts to research and disclose historic ties to slavery. But those existing laws are rarely enforced, Howard told the state commission during a recent meeting, and the model his organization is proposing would be more robust than those earlier efforts.

In the meantime, the state commission will continue to hold public hearings, while the public eagerly awaits its recommendations on reparations and worries the window of opportunity could close.

“We’re actively working to educate individuals about this issue because, let’s be honest, when you talk about that window, a lot of individuals don’t understand the difference between moments and movements,” Slaughter said. “We’re attempting to build a movement, not just a moment.”

Former Tribune reporter Kate Armanini contributed.