The Republican Party is struggling with a racism problem.

Once it became clear that the Democratic presidential nominee will be a half-Black, half-Indian woman, members of the Grand Old Party, from the top down, began launching thinly veiled and sometimes plainly racist and sexist attacks against Kamala Harris.

Republican candidate Donald Trump—who thinks “Western-style liberalism” refers to politics in San Francisco—called Harris “Dumb as a Rock” barely 24 hours after she became the leading candidate.

That same day, vice-presidential nominee Sen. J.D. Vance (R-OH) once again revived the pernicious specter of the welfare queen, saying Harris hasn’t done anything in years “other than to collect a government check,” as if being a career politician is unusual in a gerontocracy where a presidential candidate just dropped out specifically because of his age, and the leading Senate Republican, Mitch McConnell, has been collecting government checks for longer than I’ve been alive.

Vance also criticized Harris for not showing enough appreciation and gratitude for U.S. history, a sly gesture toward the racist trope that Black people and nonwhite immigrants should only be happy that they got away from the imagined savagery of Africa and other distant lands to civilization here in America.

New York Times journalist and editorial board member Mara Gay told MSNBC that the comments were “a dog whistle calling [Harris] uppity … Every Black voter in America knows that.”

Still, some other Republicans and conservatives skipped over the dog whistle and went straight for a racist bullhorn, by calling Harris a “mediocrity,” intellectually weak, and most prominently, a “DEI hire.” To be clear, Harris’s public-service record is entirely typical for a modern senator or presidential candidate, and far more robust than either Vance’s two years in public office or Trump’s nonexistent record when he first ran in 2016.

The GOP is now working to tamp down the overt sexism and racism within its ranks, holding a “closed-door meeting” on Tuesday where House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) implored his colleagues to steer clear of Harris’s “ethnicity or her gender,” the Associated Press reported last week.

Vance actually had the issue in mind even before Johnson. In his very first campaign speech, just a day after Republicans learned that they are now running against a nonwhite woman, Vance attempted to preemptively deflect the accusations of racism that he apparently expects as Trump’s (or the Republican Party’s) pick for VP.

“It’s the weirdest thing to me. Democrats say that it is racist to believe—well they say it’s racist to do anything,” Vance said. “I had a Diet Mountain Dew yesterday … I’m sure they’re gonna call that racist too.”

In case you missed it, like the crowd listening to Vance certainly did, that was an attempt at humor. But the more important point was a rejection of the accusation that his party and its platform are generally racially biased. It’s a question GOP Sen. Tim Scott (SC) has asked before: “Why are Republicans constantly accused of racism?” (Scott was remarking on a racist comment by former congressmember and open white supremacist Steve King.)

That’s a claim worth taking seriously, at least for a minute, given the choices and stakes in this year’s election.

REPUBLICANS KICKED OFF THEIR ANNUAL convention last week with plans to paper over their nominee’s extremist and divisive positions and personality, as Trump himself acknowledged in a frank but understated remark shortly afterward: “I’m not going to be nice.”

Still, it was evident from the beginning that the Republican version of diversity, equity, and inclusion is actually just an ugly form of tokenism, and that the party does not in fact have much to offer to nonwhite voters.

The first speaker on day one was Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI), whose record includes promoting the racist “great replacement” conspiracy theory. Johnson has freely admitted that he was unconcerned about the nearly all-white mob that stormed the Capitol in January 2021, but would feel differently if it had been Black Lives Matter protesters.

He was followed by Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), who also has a long and well-known history of racism, Islamophobia, and antisemitism. Greene has previously “suggested that Muslims do not belong in government … called George Soros, a Jewish Democratic megadonor, a Nazi; and said she would feel ‘proud’ to see a Confederate monument if she were black,” Politico reported in 2020. The House, including nearly a dozen members of her own party, voted to strip Greene of her committee assignments in 2021 for racist behavior and promoting political violence.

It was evident from the beginning that the Republican version of diversity, equity, and inclusion is actually just an ugly form of tokenism.

Then came Mark Robinson, the first Black lieutenant governor of North Carolina, who also has a well-documented history of anti-Black and antisemitic remarks. And there was also Charlie Kirk, a right-wing activist who appeared even though his history of racist behavior had actually caused some concern among convention organizers. Kirk has previously described DEI programs as “anti-white” and said he gets concerned if he’s on a plane with a Black pilot.

On top of all this was an explicit and indiscriminate anti-immigrant message—including signs calling for mass deportation—as well as open anti-LGBTQ and particularly anti-trans attacks.

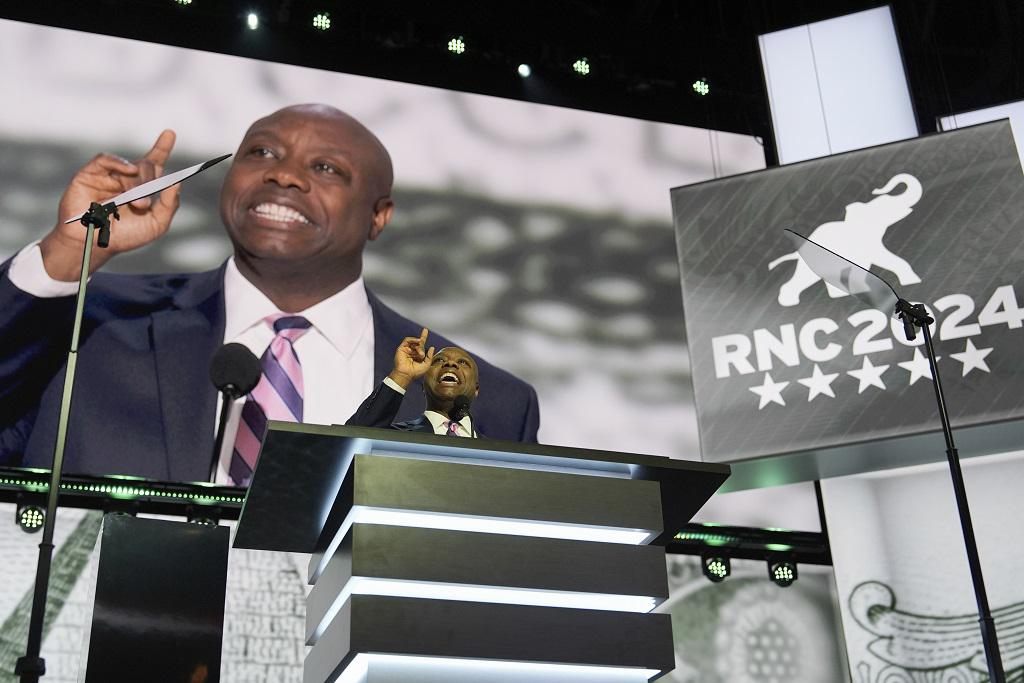

However, as in past years, the Republicans strived to quite intentionally present a more diverse and inclusive cross section of the party. In addition to Robinson, 80 percent of the Black Republicans serving in Congress were featured speakers on the convention’s first night: three of the four House members, Reps. Byron Donalds of Florida, John James of Michigan, and Wesley Hunt of Texas, along with Scott, the lone Black Republican senator.

The convention featured other Latino, Black, and even biracial speakers; invoked Greek Orthodox, Catholic, and Sikh prayers; and praised the legacies of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, alongside Ronald Reagan and Trump. The Trump campaign has also deployed Hunt and Donalds—who once made comments expressing nostalgia for the Jim Crow era—to court Black voters.

As a background matter, every single one of the five Black Republicans in Congress (the four aforementioned members and Rep. Burgess Owens of Utah) represents a majority-white district. And polling consistently shows that their political views are entirely out of step with the overwhelming majority of Black voters.

Hunt, a new member, has been quite candid about what his presence and membership in the party means, as have Republican operatives and many of his voters.

“For his supporters, Mr. Hunt is evidence that whom they vote for is driven by policy and ideology and not by what a candidate looks like,” The New York Times said in a profile in 2022, focused on the racial dynamics that defined his campaign. Supporting Black candidates reassures some voters that they and their party aren’t bigoted or discriminatory, in other words, even when those Black lawmakers have anti-Black politics or views.

Here’s how Hunt commented on the issue in an interview shortly after his RNC speech: “When you don’t see people that look like you in a party, it doesn’t look good optically, if that makes sense,” Hunt said. “I think having faces out there like mine [and Donalds’s and James’s] is very beneficial for the party for people to see that, you know what, it’s not just a party of all white people.” This is the same distorted definition of diversity and inclusion that Republicans allege in other contexts.

Each of the Black Republican lawmakers consistently runs on and presents a political vision centered around overcoming historical racism through individual perseverance; each presents a message that, at its core, rejects the role racism plays in America today, almost like some kind of purity test. An African American history scholar told The New York Times last year that it’s a message that appeals to white voters, and is generally alienating to Black Americans.

Indeed, polls show consistently that an overwhelming majority of Black Americans believe anti-Black racism is widespread in the U.S., and that most Black adults (around three-quarters) agree that the government should make efforts toward some kind of reparations for descendants of formerly enslaved people.

The Black lawmakers’ speeches at the convention presented a quite different understanding of race. James said his parents “raised me never telling me this is a racist country.” Scott echoed the same point. He added that “if you were looking for racism today, you’d find it in cities run by Democrats.”

Afterward, CNN political analyst Van Jones commented that the party’s messaging “was kind of cringey … we got four African American men… [and] all four of them sounded like Black people who talk about Black people, but don’t talk to Black people,” Jones said. He added that Scott’s and Jones’s tone when discussing the painful effects of structural racism was “off,” and almost gleeful.

Moreover, it’s fair to say that all of the Black representatives who were featured have relatively unimpressive political records. Almost all are newcomers to Congress. Donalds took office in 2021, after working for banks in Southwest Florida for several years. James and Hunt both took office last year, after careers in the military. None have any major legislative achievements to speak of, despite their prominent role in the party’s convention.

In short, Republicans trotted out basically their whole minuscule group of Black members to speak to the Black community. And their core message was that they don’t believe systemic discrimination exists, or that the government should play any role in addressing it.

BESIDES THE INDIVIDUAL REPRESENTATIVES, the 2024 Republican platform itself also doesn’t speak directly to nonwhite voters.

The first two items in the 20-point GOP platform list include coded anti-Latino language about stopping a “migrant invasion,” and promises for the “largest deportation operation in American history,” including “moving thousands of Troops currently stationed overseas to our own Southern Border.”

Item No. 16 is perhaps the only other plank that speaks directly to issues of race, and it’s a promise to cut federal funding for schools that teach about racism and what the party calls “other inappropriate racial … or political content.” Item No. 19 promises to continue to pass racially discriminatory laws that make it harder to vote.

So why would a party have virtually its entire Black delegation appear on stage to preach a message that appeals to vanishingly few Black voters, while selling a platform that’s antithetical to the issues specific to most Black voters’ lives?

Tokenism, in a word.

Of course, there are other, more obvious signposts, like the top of the party’s ticket. The presidential nominee and de facto party leader has been accused of racism throughout his many decades in public life, including in a lawsuit by the federal government in the 1970s. He is likely the only president who has ever been officially condemned for “racist comments” by the U.S. House in a formal congressional resolution.

He has broad support among white nationalists and has been described as “racist” in headlines by most major American media, including The Washington Post, CNN, The New York Times, and the Associated Press. “I think he is a racist,” said former civil rights leader and representative John Lewis in 2018.

The government of Haiti, a former justice minister of Germany, and the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights have also called Trump racist. And he’s been described as bigoted by the 55-member African Union and a number of African politicians, including the current Ghanaian president.

Some of Trump’s Republican colleagues have also acknowledged his bigotry. Former RNC chairman Michael Steele has said that the evidence of Trump’s racism is “incontrovertible”; former House Speaker Paul Ryan has accused him of textbook racism; Mitt Romney has said that Trump’s words “caused racists to rejoice” and accused him of perpetuating “trickle-down racism”; and Lindsey Graham, one of Trump’s most ardent boosters, called him a “race-baiting, xenophobic religious bigot” back in 2015.

Indeed, yet another account of Trump’s racism was revealed just this week, when his own nephew disclosed an exchange in the 1970s during which Trump went on an angry rant against “ni****s.”

Despite Vance’s weird Mountain Dew “joke,” accusations of Republican racism didn’t just fall out of a coconut tree. They are a result of a context in which Republican messaging, membership, platform, voters, and leaders repeatedly and continuously express racially discriminatory beliefs.

True to their word, Republicans in fact do not believe in diversity, equity, or inclusion. We can safely assume that their racist and sexist attacks against Harris will continue, as will their racist and sexist policy proposals, and their token uplifting of the meager handful of Black people willing to sell that message.