As the new Democratic standard bearer, Vice President Kamala Harris has described her contest with former President Donald Trump in blunt terms — tough prosecutor versus civil and criminal defendant.

“I took on perpetrators of all kinds, predators who abused women, fraudsters who ripped off consumers, cheaters who broke the rules for their own game,” Harris said at a rally in Wisconsin on Tuesday. “So hear me when I say I know Donald Trump’s type.”

But critics say that Harris’ record as a prosecutor, first as the district attorney in San Francisco and later as the California attorney general, reveals a political chameleon rather than a tough-on-crime top cop, according to interviews with current and former law enforcement leaders across the state, civil rights advocates and politicians.

In a statement, Harris campaign spokesperson James Singer said, “During her career in law enforcement, Kamala Harris was a pragmatic prosecutor who successfully took on predators, fraudsters, and cheaters like Donald Trump.”

Harris has written two books about her time as a prosecutor and attorney general. In her 2009 book, “Smart on Crime: A Career Prosecutor’s Plan to Make Us Safer,” published near the end of her tenure as DA, Harris described herself as a prosecutor who was “tough on crime by being Smart on Crime,” said she promoted programs to fix recidivism and made “improving my office’s felony conviction rates my number one priority.”

Five years later, after the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, which vaulted the Black Lives Movement onto the national stage and made criminal justice reform a top issue, Harris embraced the calls for change.

In her 2019 memoir, “The Truths We Hold: An American Journey,” published while she was senator, Harris described herself as a “progressive prosecutor.”

“I knew I was there for the victims. Both the victims of crimes committed and the victims of a broken criminal justice system,” Harris wrote. “For me, to be a progressive prosecutor is to understand — and act on — this dichotomy.”

Trump and his allies are now trying to emphasize the “progressive” part of Harris’ identity. On Tuesday, the former president attacked Harris as a “radical left person” and blamed current crime in the city on her tenure as district attorney.

“Really, what you should do is take a look at San Francisco now compared to before she became the district attorney, and you’ll see what she’ll do to our country,” Trump said.

‘Tough’ and ‘compassionate’

Harris, the daughter of an economist and a scientist, was born in Oakland, grew up in Berkeley and graduated from Howard University in 1986. She then attended the University of California law school in San Francisco, then known as Hastings, graduating in 1989, according to her congressional biography, and immediately began working as a prosecutor. She first worked at the Alameda County District Attorney’s office, prosecuting child sexual assault cases and later moved to the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office, which provides legal services to the city and represents it in civil claims; she served as head of the office’s division on children and families.

Louise Renne, who as San Francisco city attorney at the time was Harris’ boss, said she hired Harris because she was known for being “tough on the law” as well as “compassionate and kind,” Renne told NBC News in an interview this week.

In 2003, after working five years in San Francisco, Harris was elected the city’s first Black, South Asian and female district attorney.

During her seven years in that office, Harris began formulating a reputation of being a careful prosecutor committed to holding individuals who commit serious crimes accountable and helping nonviolent offenders turn their lives around.

Lateefah Simon, who started the office’s first youth offender re-entry division under Harris, praised her approach.

“She’s the only district attorney that I would ever work for to this day, because I believed the ethics that she put into the office,” said Simon, who is now running for Congress in the Bay Area as a Democrat. “She tried to create an office that was fair and balanced.”

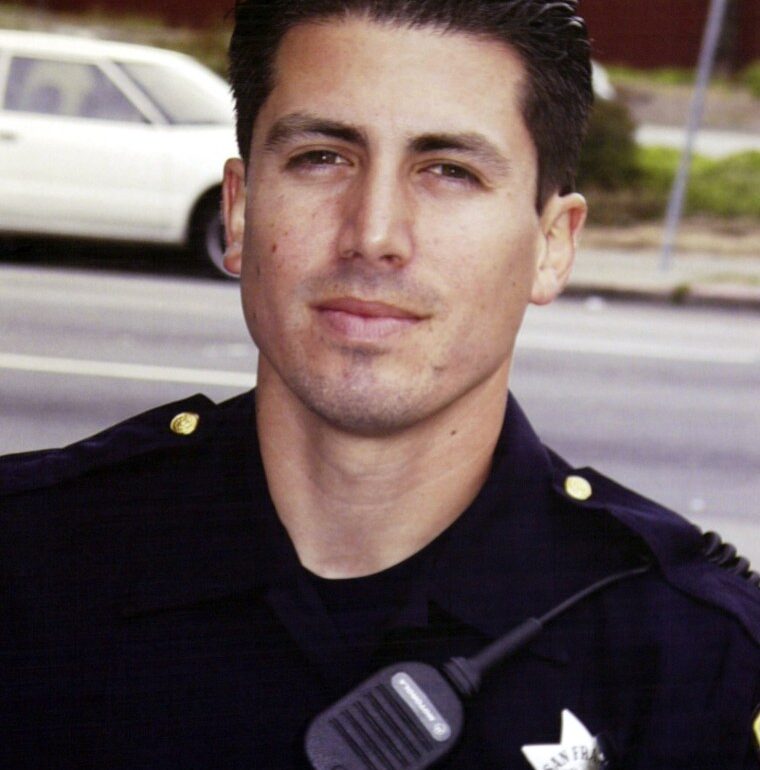

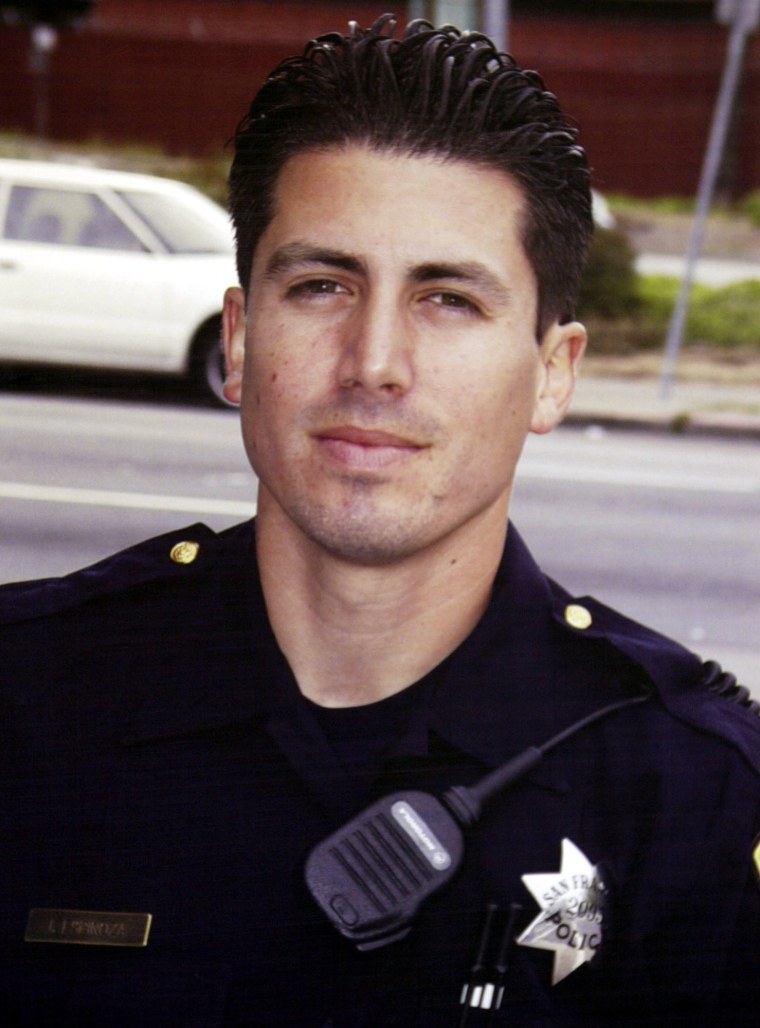

Four months after Harris was sworn in, a gang member shot and killed police Officer Isaac Espinoza in April 2004. She declined to charge the gunman with a capital offense, sparing him from the death penalty. Harris’ decision rankled California’s political leadership.

During Espinoza’s funeral, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., slammed Harris’ decision. “This is not only the definition of tragedy, it’s the special circumstance called for by the death penalty law,” Feinstein said at the time.

Throughout her tenure as district attorney, Harris focused on securing convictions. Felony conviction rates rose from 52% to 71%, and gun crime convictions rose to 92% in the first five years she was in office, according to her book.

“We are sending three times as many offenders to state prison [as] we were in 2001, three years before I took office,” Harris wrote in her 2009 book.

She also increased convictions for drug sellers, from 56% in 2003 to 74% in 2008, Harris noted. At the same time, Harris also implemented the Back on Track program, which provided nonviolent offenders — many of whom were low-level drug dealers — with the chance to receive a high school diploma, job training and access to available work, instead of prison sentences.

“The imperative today is both to go after the worst criminals and also to redirect the future of lower level offenders,” wrote Harris in her 2009 book.

Her relationship with progressives grew strained. She pushed for the prosecution of truancy cases — which resulted in the parents of children who were habitually absent from school being prosecuted and forced to pay fines of up $2,500 and potentially serving up to a year in jail. Some critics said the policy disproportionately affected Black families.

A Harris campaign aide said the policy was effective: “Truancy dropped by 33 percent because of the policy and it also helped people in the community — this wasn’t one or two days; this was kids missing 60 to 80 days out of a 180-day school year.”

Harris clashed with San Francisco City Council policy regarding undocumented immigrants. In 1989, the council had made San Francisco a “sanctuary city,” which meant that local police were generally not allowed to share any information with federal immigration agencies that they had obtained from interactions with undocumented people.

Harris, along with then-San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom, later supported a policy that would require law enforcement to notify U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement if an undocumented juvenile immigrant was arrested under suspicion of committing a felony.

David Campos, who has served on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors as well as the Police Commission, said he and other progressives have not always agreed with Harris, but supports her bid for the presidency.

“She will be able to bring forward an experience, that perspective, that points to results where she was able to thread that needle between being tough on crime and also being reform-minded when it comes to criminal justice,” said Campos, who is now the vice-chair of the California Democratic Party.

A Harris campaign aide said, “If you’re angering the far left and the far right, you’re probably doing something right.”

Prison reform

Several years after Harris was elected state attorney general in 2010, California voters passed a ballot measure that enacted sweeping sentencing reforms across the state. In an effort to relieve overcrowding in the state’s prison, the proposition reclassified a list of felonies as misdemeanors, including certain drug crimes and theft — including shoplifting of property valued at less than $950.

The attorney general’s office under Harris released a summary of the law, called Proposition 47, which predicted that prison and jail populations would decrease while funding for truancy reduction programs and mental health services would rise. It also predicted that the state criminal justice system would save hundreds of millions of dollars due to the changes, and local prosecutors and sheriffs would have reduced workloads.

As of last week, prison officials reported, there were 92,480 people locked up in California’s prison systems, down from a height of more than 156,000 inmates during the early 2010s before the law was passed. But as NBC News reported last year, California’s reforms created a prison-to-homelessness pipeline, as counties were overwhelmed with an influx of returning inmates.

Violent crime, meanwhile, has increased across the state. The state attorney general’s office reported that from 2014 to 2023, violent crime had risen by more than 30% — including jumps in rapes, aggravated assaults and murders.

Although Harris didn’t take a formal position on the measure, Republicans accused her of misrepresenting Proposition 47 to the public. Steve Cooley, who served as the Los Angeles County district attorney from 2000 to 2012, blamed the rise in crime on Harris and the referendum.

“The damage has been untold and, in a sense, irreparable,” said Cooley, who ran as a Republican against Harris for attorney general. “It was beyond a bait and switch. It was fraud by misrepresentation.”

Critics also blame a rise in retail theft in California on Proposition 47. They say the reforms enable serial shoplifters to cycle in and out of police custody with little accountability. Even if they are repeatedly arrested, they are only charged with misdemeanors as long as the goods are valued at less than $950.

Frustration over shoplifting is now driving voters to try to amend the law. In November, California residents will decide whether to amend Proposition 47 to allow people with two theft convictions to be charged with a felony after being caught stealing a third time. It would also permit judges to sentence repeat “hard drug” offenders to prison instead of jail.

Douglas Eckenrod, a former deputy director of parole for the California prison system, who is now running for sheriff as a Republican in Sedona, Arizona, said Harris was too lenient on criminals.

“Kamala Harris is not a hard-liner [on crime],” Eckenrod said. “Prop 47 couldn’t happen without the AG’s office support. Her support of it was literally critical.”

In 2017, Harris left her post as California’s attorney general after being elected to the U.S. Senate.

Police reform

Harris’ relationship with both police officers and police reform activists has been fraught.

When she ran for attorney general in 2010, the San Francisco police union president did not back her, citing her refusal to seek the death penalty in the killing of Officer Espinoza. “That is a relationship that is never going to be OK,” union boss Gary Delagnes told SF Weekly at the time.

Harris also attracted criticism from those on the left. Civil rights attorneys and police reform advocates lambasted her for failing to charge police officers who they said had used excessive force in deadly confrontations.

John Burris, an Oakland-based civil rights attorney who has sued police departments and officers across the state, said he couldn’t recall a police violence case that Harris, as San Francisco district attorney and later as California attorney general, chose to prosecute. But he added, prosecutors during that era rarely challenged police officers.

“It’s no secret that prosecuting police in shooting cases is an uphill battle for the most part,” Burris said. “I thought that she appreciated those issues, even though I didn’t necessarily agree with the ultimate decision.”

Harris also rarely used a state law, enacted in 2001, that allows the attorney general to investigate problematic local law enforcement agencies for widespread abuses. In December 2016, weeks before she was sworn in as senator, Harris announced that her office would investigate the Kern County Sheriff’s Office and the Bakersfield Police Department over allegations of excessive force and serious misconduct.

A spokesperson for California Attorney General Rob Bonta, a Democrat, defended her record and said in a statement to NBC News that Harris also opened an investigation into the Stockton School District and its school police department. The California Department of Justice later found that the Stockton school district had referred a disproportionate number of Black, Latino and disabled students to law enforcement.

The spokesperson also noted that Harris launched an open data initiative that releases the number of law enforcement officers killed or assaulted on the job, the number of people who die in custody, and the number of arrests and bookings. She also announced new requirements for reporting officer-involved shootings and use of force incidents.

Despite complaints that she failed to hold police accountable for abusive behavior, Harris said in her 2019 memoir that she supported the mission of Black Lives Matter. She credited the protests for motivating her to make several policy changes.

Harris wrote that she required officers in California to attend anti-bias training and ordered some state-level officers to start to wear body cameras.

“I was able to do it because the Black Lives Matter movement had created intense pressure,” Harris wrote. “By forcing these issues onto the national agenda, the movement created an environment on the outside that helped give me the space to get it done on the inside.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article misstated where Harris grew up. She grew up in Berkeley, not Oakland (where she was born).