Black players were always part of baseball’s history. Following the 1896 Supreme Court decision that enshrined segregation into law, Black players formed their own teams.

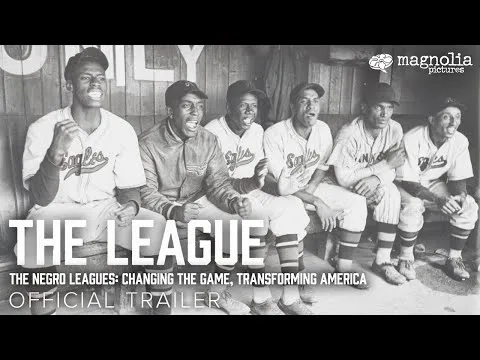

The new documentary “The League,” directed by Sam Pollard, delivers stories of the players, the entrepreneurs and communities behind the Negro Leagues.

The documentary covers more than a century of history, starting after the Civil War and before Jim Crow.

“African Americans have been playing baseball as long as white people have,” says journalist Andrea Williams in the film. “As the sport begins to take hold in popularity post-Civil War, Black people were there, always.”

Negro leagues emerged in cities with rapidly growing Black populations as a result of the Great Migration north.

The teams contributed largely to the economy in these segregated communities.

“There were stores, there were funeral parlors and there were Negro League owners who had their own franchises,” Pollard says. “These gentlemen – and ladies – were entrepreneurs.”

Rube Foster was a dazzling player and pitcher credited with inventing the screwball. He became a founder of the Negro National League right after a season of brutal racial violence in cities across the country dubbed the Red Summer of 1919.

“Rube Foster, in my own estimation, is the greatest baseball mind this sport has ever seen,” says Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. “Rube Foster was light years ahead of his time.” Kendrick says.”

Foster owned and managed the Chicago American Giants. In 1920, he pushed other Black owners from cities around the country to organize, band together and create the Negro National League.

Foster emphasized a style of baseball play that’s quick, acrobatic and stealthy with lots of base stealing. It stood in contrast to the more static style in the major leagues that relies on home run hits out of the ballpark.

Foster died ten years after founding the Negro League. He was so beloved that in Chicago, people poured out into the streets for three days to honor him.

In the 1930s, Pittsburgh became the center of Black baseball with two teams and two prominent owners leading the way: Cumberland Posey of the Homestead Grays and Gus Greenlee of the Pittsburgh Crawfords.

“That was another major heyday,” says Pollard.

A lot of big-name players emerge including Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell. Satchel Paige quickly secured his spot as a legendary player.

“In one game, he called in the outfield and had them sit behind him as he struck out three batters with nine pitches,” Pollard says. “That’s how great he was.”

The film features archival footage of several Negro League players. They describe life on the road during Jim Crow, sleeping on buses and inside ballparks. Players share stories of traveling to the Caribbean for winter ball and describing the freedom they find.

“The notion that a Black man can go to the Caribbean and play baseball without feeling the same kind of pressure and psychological baggage that you had to deal with in America, had to be something that was emotionally and psychologically invigorating,” says Pollard.

One prominent owner of a Negro League team was a woman named Effa Manley. She owned the Newark Eagles with her husband, Abe Manley, and helped lead the team to win the Negro League World Series in 1946.

One year later, Jackie Robinson famously broke the color line and joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. Black communities across the country celebrate him, but partially at the expense of the Negro League. Black fans flocked to major league ballparks to watch Robinson and other stars, which started to hollow out Negro League stadiums.

Dodgers owner Branch Ricky, mythologized in history as a savior who brought Robinson to the big leagues, never compensated Negro League owners.

“I never felt he was right to take those valuable players and not give us a nickel for them. I felt that was very wrong,” Effa Manley said in archival footage.

Maney’s team, the Newark Eagles, was sold a year after Robinson crossed the color line. Other Negro League teams also folded.

“By the 1950s, they were barely hanging on, and by 1960, the Negro Leagues were gone,” says Pollard.

Pollard says learning about the life of the Negro Leagues is important.

“It’s another opportunity for all Americans to understand that American history is not just white history. You know, it’s a history that involves people of color, native people, African American people who are all part of shaping the direction of this country,” Pollard says. “When I make these films, I want people to know our stories are part of the American story.”

“The League” is available to stream on Apple TV and Amazon Prime.

Shirley Jahad produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Catherine Welch. Jahad also adapted it for the web.