Published on

A ‘tremendous opportunity.’ Northeastern researchers dig into Boston’s past in support of Boston’s Reparations Task Force

Next Tuesday, June 25, reparations will be taken up once again as Boston’s task force meets. Northeastern’s research team, focusing on 1940 to the present, is led by distinguished professors Margaret Burnham and Ted Landsmark.

The idea of reparations has a long history in Massachusetts — dating to at least 1773 when an Essex County court found Richard Greenleaf liable for £18 for trespassing to enslave Caesar Hendrick.

Next Tuesday, June 25, reparations will be taken up once again, as the City of Boston Reparations Task Force meets.

A research team from Northeastern University is playing a key supporting role.

“There is a lot of movement around the country as relates to the issue of reparations,” says Deborah Jackson, managing director of Northeastern Law’s Center for Law, Equity and Race and project manager of the Northeastern research team. “To be on the ground floor of the city of Boston’s effort to understand, address and reconcile with its past is a great and tremendous opportunity.”

Boston established the Reparations Task Force in accordance with a city ordinance. Members of the task force were announced in 2023 and the city announced this year that two research teams would “study and document that city’s role in, and historical ties to the transatlantic slave trade and the institution and legacies of slavery.”

Northeastern researchers leading the way

Members of the Northeastern community were selected as one of those teams.

The Northeastern research team is led by University Distinguished Professor of Law Margaret Burnham, faculty co-director of CLEAR, and director of both Reparations and Restorative Justice Initiatives and the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern.

The research team also includes Ted Landsmark, a distinguished professor of public policy and urban affairs, and the director of the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern.

Other researchers include Richard O’Bryant, director of the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute; Giordana Mecagni, head of Archives and Special Collections at Northeastern’s library; Kabria Baumgartner, dean’s associate professor of history and Africana studies; community leader Donna Bivens; and Peter Enrich, a professor emeritus of the Northeastern University’s School of Law.

The team has also partnered with Zebulon Vance Miletsky, associate professor of Africana studies at Stony Brook University and the author of “Before Busing: A History of Boston’s Long Black Freedom Struggle.”

Focus on the years 1940 to the present

The team is focused on the years 1940 to the present. A team from Tufts University is focused on the years 1620 to 1940.

“Our city’s leaders have opened up a vital opportunity for those who live and work here to learn about how slavery and its wide-ranging aftermath have impacted our common history as well as our unique experiences,” Burnham says.

“Our team at Northeastern University looks forward with great enthusiasm to providing research support. Our work will, we hope, both inform the mission of the Reparations Task Force and offer insights into these past events for constituencies across the city.”

Jackson says the team’s work is an extension of the work the CRRJ project has been doing over the years and is focused on three main areas: the movement around school desegregation; employment, specifically as related to the city’s police and fire departments; and policies through the Boston Housing Authority. The research is expected to take up to one year.

Special collections informing the team’s research

Deep in the basement of Snell Library, Mecagni and reference and outreach archivist Molly Brown displayed boxes of documents from the university’s special collections that will inform the team’s research.

“In the university archives and special collections we collect and make available the history of underrepresented communities in Boston and we also do work on neighborhoods that are contiguous with the Boston campus,” Mecagni says. “This work really plumbs the depths of our expertise and our collections.”

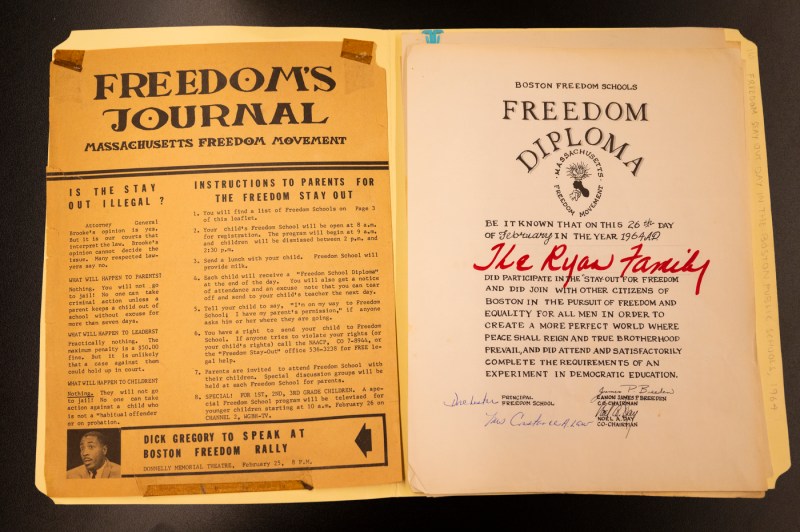

Wearing white cotton gloves, Brown showed pictures from Freedom Schools — schools formed for students participating in “school stay out days” — boycotts to protest segregation on designated days in the early 1960s, as well as documents from the formation of Operation Exodus, a voluntary school desegregation program that helped Black students in the city enroll in predominantly white city schools and was the predecessor to the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO) program.

The archives also include records from Paul Parks, the first African American secretary of education for Massachusetts as well as the first African American on the Boston School Committee. The papers document racial imbalance and the unequal quality of education experienced by Blacks and whites in Boston Public Schools and other civil rights leaders who worked to identify these harms and fight to make change.

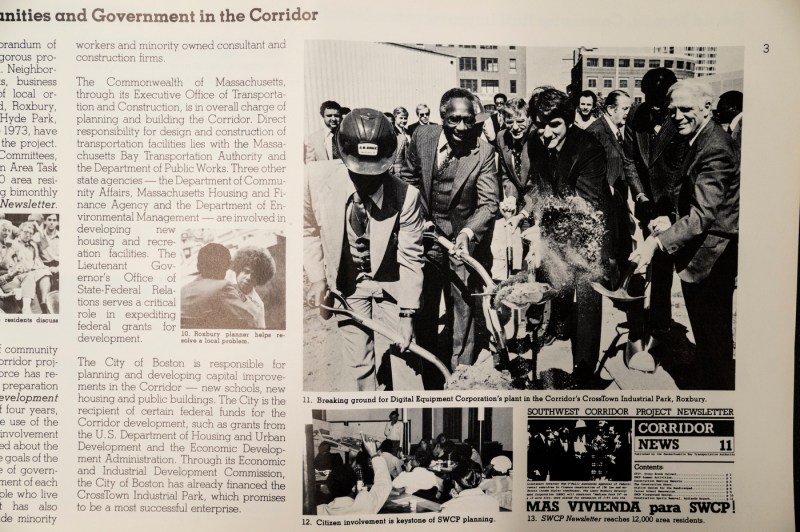

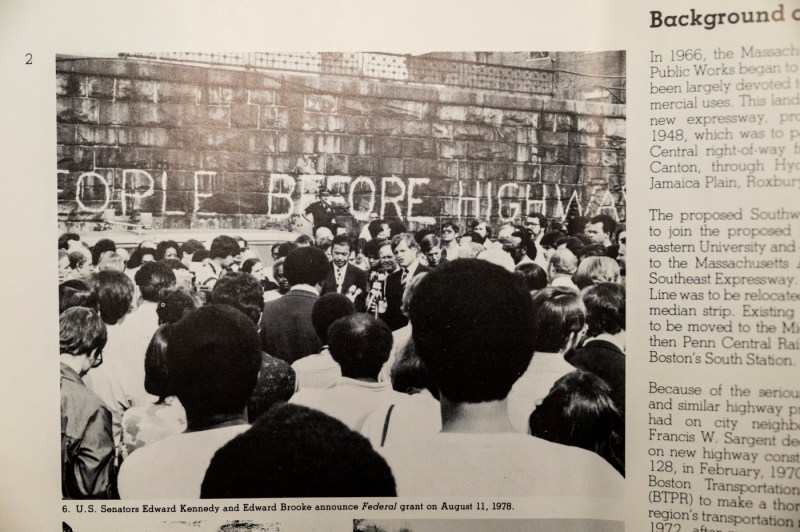

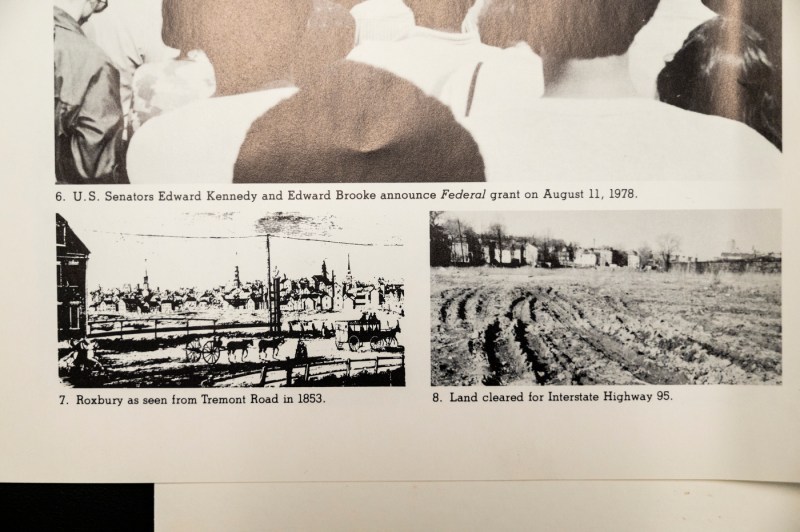

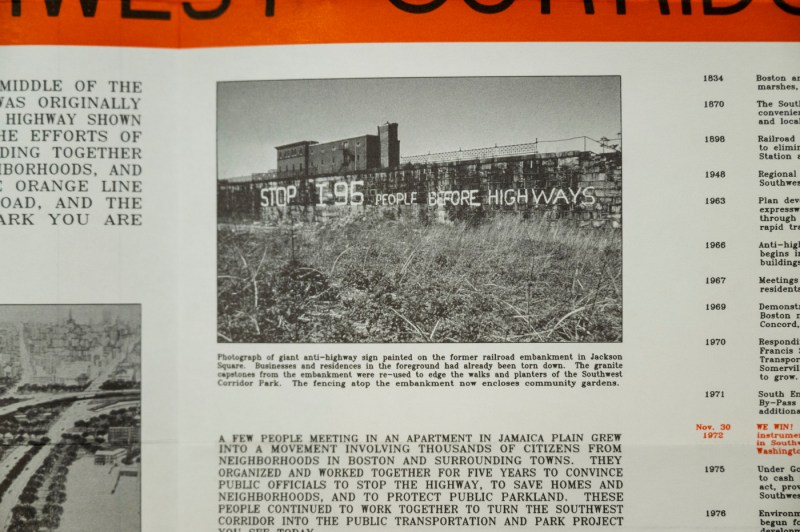

And there is extensive documentation of inequities in homeownership opportunities offered to veterans in the GI Bill, records of the demolition of the West End and documents related to plans for the 12-lane Southwest Corridor highway project, which was ultimately blocked by activists whose homes and neighborhoods had been eliminated and were at risk of demolition.

Graduate students assisting with the project

But these were just a sampling of the resources that researchers — including graduate students who are assisting with the reparations project — are combing through.

“Our role is to help them navigate where the archives live that they would be able to find and to present evidence of inequities,” Brown says.

“The trick is to lay out all the evidence that this inequity happened so the city can decide what to do with it,” Mecagni says.

Indeed, the teams’ results will inform the task force’s recommendations for next steps.

Landsmark, a longtime social activist, says being named to the task force is an opportunity.

“A number of historians and activists have been working in this field for decades, and our work is a ‘bringing to fruition’ of prior research and activism with an expectation that actions can now be taken to redress the disparities that previous work have revealed,” Landsmark says.

“It’s an opportunity for us to continue important work on social justice and equality in Boston and across New England.”

Cyrus Moulton is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.moulton@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @MoultonCyrus.