The topic of restitution for Black Americans is highly contested. Now that the conversation has entered the mainstream, what is the solution?

Over time, the movement for reparations has persisted, grown louder, and pushed the argument forward, but critics insist these efforts lack real weight, and don’t answer the most pressing question at hand: Where’s the cash?

This past January, Governor Kathy Hochul posted a statement on X, but she and her team had no idea that a simple, end-of-the-year boast that “New York has secured over $183 million in compensation for Holocaust victims and their heirs” would result in a firestorm of criticism from thousands of users of the social media platform.

Some posters wondered why Holocaust victims receive compensation while Black Americans have received “nothing.” @P.Y.T on X said, “This is a literal slap in the face to African Americans. Compensation for holocaust victims where the trauma didn’t even take place on American soil.”

Filmmaker Yoruba Richen discovered this debate firsthand while making her documentary “The Cost of Inheritance” in 2023. Part of the film investigates the history of Georgetown University’s reparations. The university admitted in 2014 that the institution had sold 272 enslaved people in 1838. In response, the university created The Reconciliation Fund in collaboration with some of the descendants. However, not all of the descendants are on the same page due to the lack of cash payments.

RELATED: Making the Dream Real: The Past, Present and Future of Reparations

“There is another group of descendants who are fighting for cash payments,” said Richen, who was surprised by the lack of agreement. “They are not interested in a foundation.”

Those who call for cash payments for descendants of enslaved Black Americans point to historical examples. A century ago, the Pueblo Lands Act of 1924 forced the government to pay $1.3 million to the Pueblo for the land they lost. More recently, Natives in Alaska received $1 billion and 44 million acres of land in 1971 to make up for destroying their claims to the land. In 1988, victims of Japanese internment camps received $20,000 per person.

These examples show that the government has a long history of paying when there’s a mistake made on their part. Critics wonder why there is a hold-up for Black Americans.

Even ˆ. .journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, who created the 1619 Project, commented, “Why is there such an aversion to doing something similar for descendants of slavery and the living victims of US apartheid?”

@P.Y.T. and Hannah-Jones are part of a growing movement of individuals who are tired of waiting for the government to pay what they feel they’re owed.

Some officials are starting to pay attention.

In 2020, California became the first state to create a task force to examine the possibility of reparations for Black Californians affected by the effects of slavery and discrimination. The only other state that has followed suit is New York, which created a committee in 2023. Some cities have followed suit, with Evanston, Ill., offering up to $400,00 in 2021 to purchase or repair property because of the history of housing discrimination.

In January, California took another step forward: Its Legislative Black Caucus announced a package of 14 bills that will be a part of a multi-year plan. The bills are aimed at fixing the injustices toward Black residents through compensation, apologies, and community programs.

Despite this forward momentum, though, many Black Americans feel that these gestures toward repair don’t go far enough. Those like AL D., who goes by @Colorfullstory on social media, want money. “I was frustrated by many who say we should just get over how our country [treated us],” said AL D, a former American history teacher, who now creates content that teaches about Black history to challenge what many have been taught. “Our ancestors built for free. There is no payout but there are many excuses.”

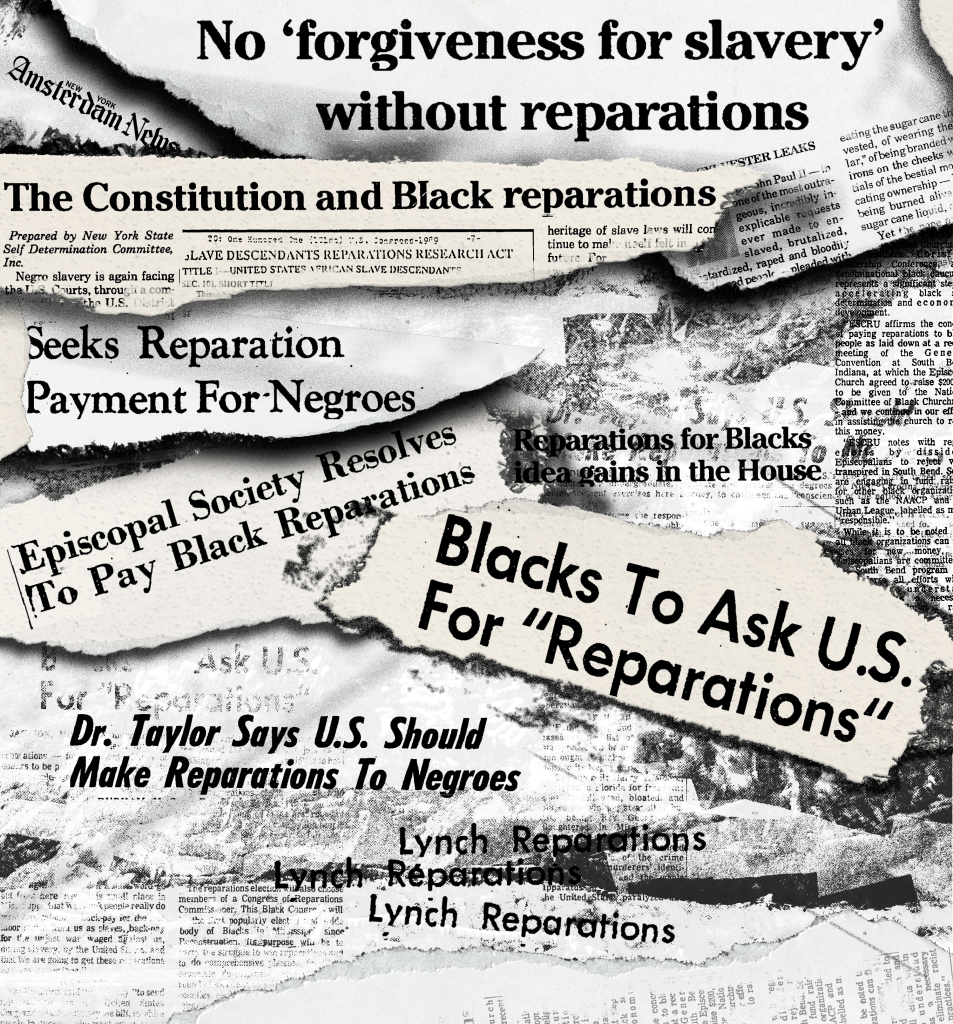

These feelings are fueled by the contentious conversation about reparations that has picked up steam over the last few years, but the debate traces back to the Civil War.

The U.S. government first attempted to provide compensation to those who were formerly enslaved nearly a century and a half ago through Special Order 15, better known colloquially as “40 acres and a mule.” On January 15, 1865 Union General William T. Sherman gave the order, which promised 400,000 acres of newly gained land, from the coastline of South Carolina down to Florida, to freed Black people in 40-acre increments. The order never came to pass because by the fall, President Andrew Jackson rescinded the order and returned the land to the former owners.

The answer seems to lie less with the government and more with American attitudes. A Berkeley poll in 2023 found that 60 percent of Californians were not in favor of cash payouts for descendants of chattel slavery. Katherine M. Franke, a Columbia University law professor and the author of the book “Repair: Redeeming the Promise of Abolition,” believes the opposition is twofold.

First, not being able to see, meet, or hear from people who were enslaved seems to make the damage seem long ago and easier to ignore. “There [were] still plenty of people around who had been encamped during the Holocaust, and the same with Japanese Americans who received reparations,” said Franke. “That campaign was undertaken by people who had been interned.”

She added another piece: “Racism is the answer. Repairing the injuries of white people may be more compelling for white people than repairing the injuries of enslaved Black people.”

It seems that the solution to the reparations issue will be long and contested, and probably a combination of all of what advocates are seeking. AL D. feels that the fight will extend beyond her.

“I can’t see it in my lifetime, nor in my children’s,” she said, “but I truly hope if I have grandchildren, we will see it.”