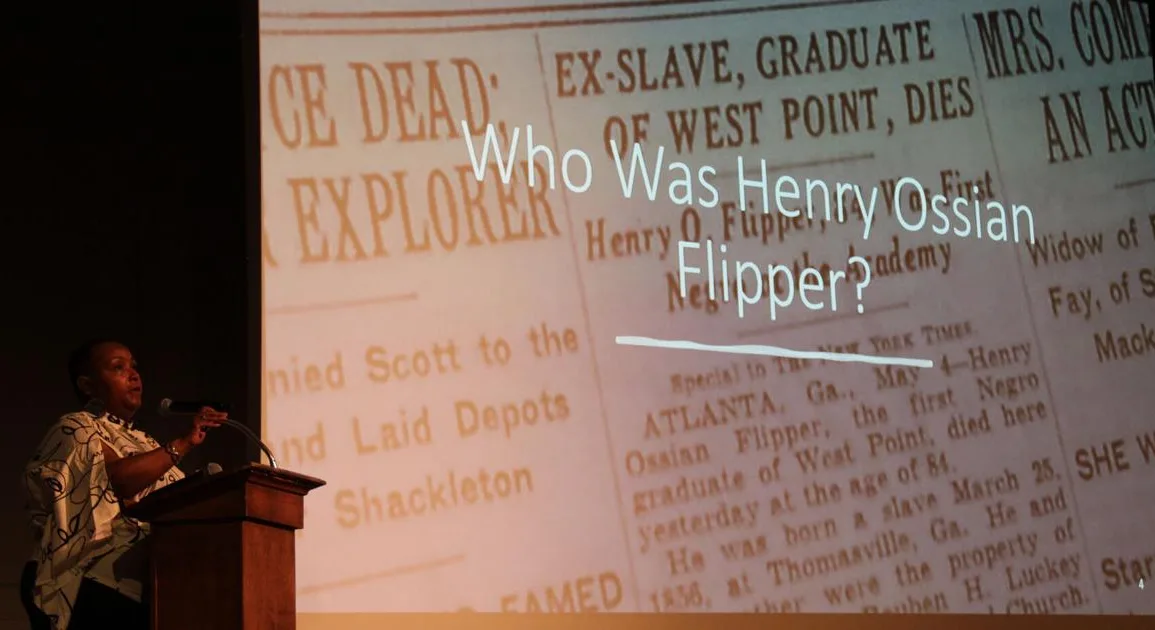

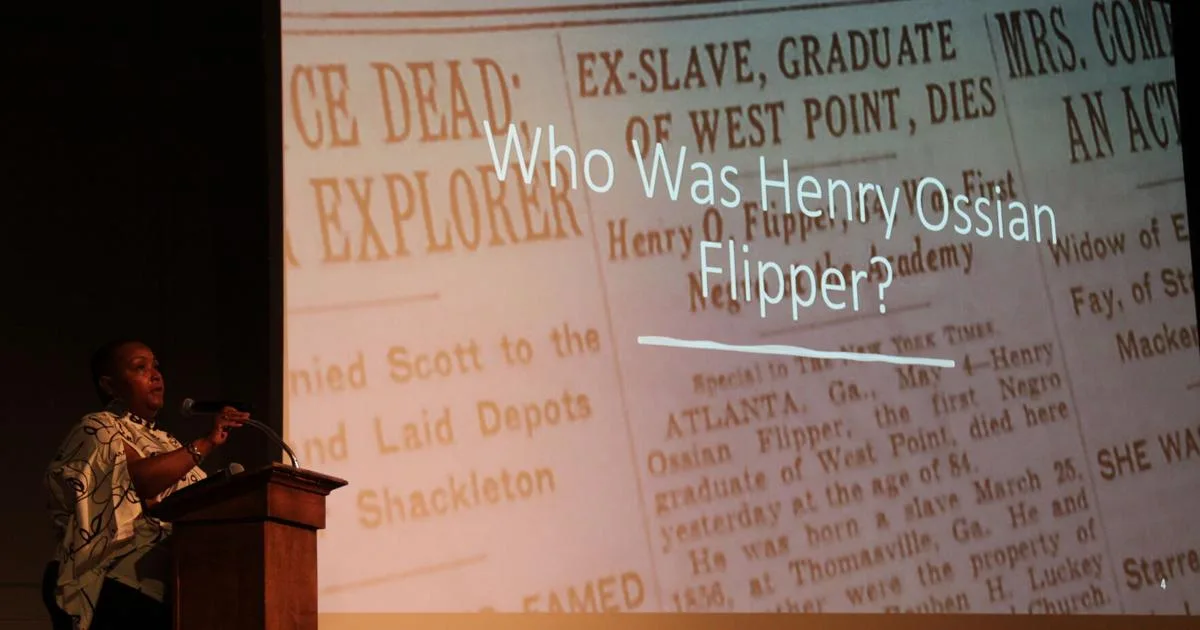

THOMASVILLE- Last Wednesday, the Thomasville History Center hosted a public lecture at the Thomasville Center for the Arts about Henry O. Flipper titled, “The Life and Times of Henry O. Flipper.”

The lecture was led by Professor Le’Trice Donaldson, an assistant professor of history at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi and author of “Duty Beyond the Battlefield: African Americans Soldiers Fight for Racial Uplift, Citizenship, and Manhood, 1870-1920,” and went into the life of Flipper, the first African American graduate at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Born enslaved in Thomasville, Georgia in 1856, after graduating, Flipper earned a commission as a second lieutenant in the United States Army, before being assigned to one of the all-black regiments. He was eventually court-martialed and dismissed the from the U.S. Army, which was changed to a good conduct discharge in 1976 and was posthumously pardoned in 1999 by President Bill Clinton.

“A big part of our

research is revolving around the narrative surrounding African American soldiers,” Donaldson said. “As someone who has been a lover of history since elementary school, when I got to college, after my undergraduate, I didn’t discover Henry Flipper until I was a grad student and upon examining his life, looking at the scholarship written about him, I was a bit perturbed by the fact that they didn’t explore beyond his court martial, and beyond the persecution he experienced at West Point.”

A self-described “lone warrior” in studying Flipper’s approach to the African American community and politics throughout his life, Donaldson said that the public’s memory has come full circle for Flipper.

“One thing that is important to think about when we reflect on Henry Flipper, is that for the most part, up until recently, as in 2005, his entire public memory has been completely revitalized and has essentially come full circle,” she said. “In that, he went from being obscured, unsung, forgotten side note to now being, whenever you just type him in, he has an award at West Point, in 2005, a journalist put him in the same category as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, in his level of importance and his advocacy for racial justice.” And yet, while some equate Flipper to equal importance in racial advocacy on behalf of the African American community, according to Donaldson, he wasn’t actually very active in that regard.

“Yes, he was a trailblazer, but his advocacy for racial uplift and for the black community, not so much,” she said.

Seeing Flipper as a complex human being, Donaldson said that Flipper’s political views at the end of his life were opposed to Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, not believing in the type of state and federally funded programs being advocated for around 1936, which he expressed in letters to Dr. Thomas Jefferson Flanagan.

“He just believes that if you give African Americans a fair shot that they can work and shape their own destiny, they don’t need government federal aid,” Donaldson said.

Donaldson compared Flipper to his contemporaries, such as Charles Young, Johnson C. Whittaker and John Hanks Alexander, in terms of importance to the African American community at the time, which Flipper paled in comparison to during his time, despite his initial claim to fame.

“When he graduated from West Point in 1877, he was the most famous black person in America,” Donaldson said. “So who was Flipper?”

During the lecture, Donaldson spoke on his many other stations in life beyond his time serving in the army, such as his volunteering to fight in the Spanish-American War in 1898, his service as an assistant to Secretary of Interior Albert Fall in 1921 and his venture to Venezuela as a petroleum engineer.

Not to mention, Donaldson said, Flipper being the first to translate and write down the history of Estevanico, the first African to explore North America. A historian, an agent, an engineer and an adventurer, Donaldson said that he was a lot of things at the end of the day.

“There are so many aspects to this,” she said. “To him, as a person.”

Continuing the lecture, Donaldson detailed and dissected the many sides of Flipper, his relationships with other African American figures of his time, and the views he held, as well as his interest in privacy, that kept him from public memory until recently.

The lecture was made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, with the lecture being a part of a one-week funded NEH Landmarks in American History workshop called “The Quest For Freedom” that examines the long journey of the civil rights movement.