For Black communities, and especially Black men, mental health can often be a taboo subject, but actor Courtney Vance is fighting to bring the issue out of the shadows.

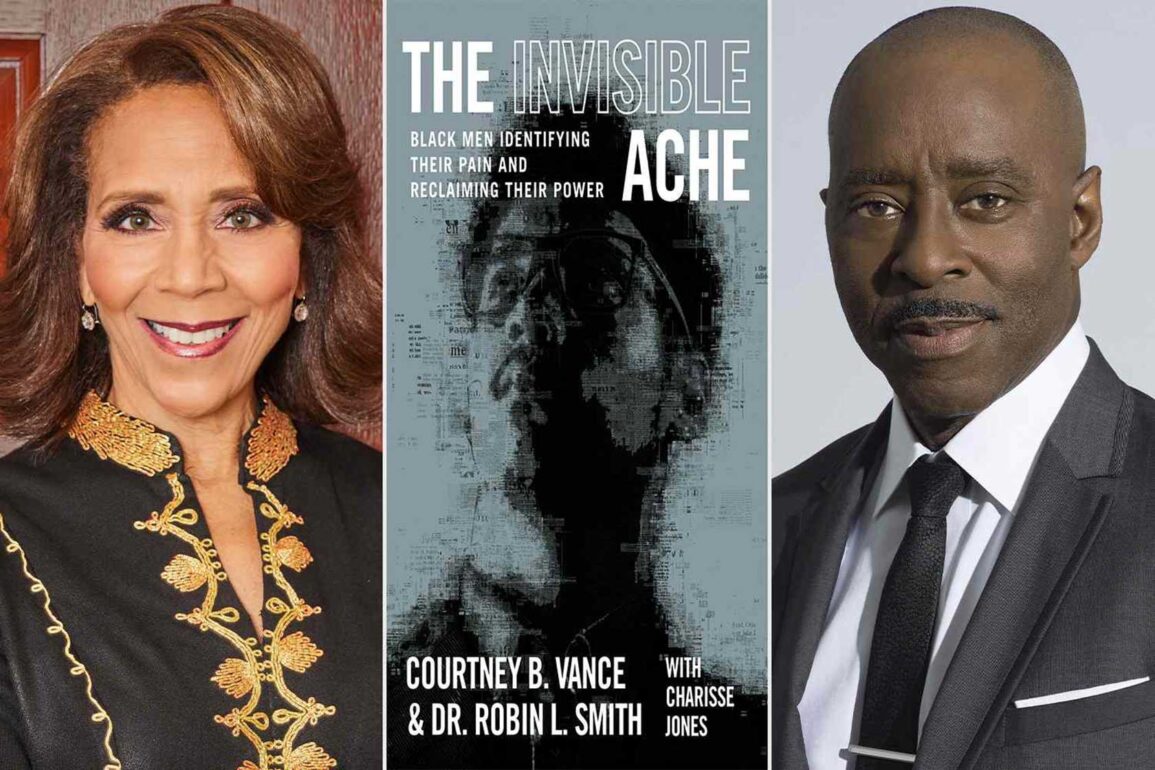

A May 8 webinar, hosted by the Give Black Alliance — formerly New England Blacks in Philanthropy — featured the award-winning stage and screen performer along with psychologist Robin L. Smith as they discussed their book “The Invisible Ache,” which was published in November.

The book — part memoir of Vance’s own struggles with his mental health as he coped with the death of both his father and godson by suicide, part psychology guidebook — is a tool that both authors said they hope will guide people to take the first step in addressing mental health challenges.

“We have to be encouraged to go down this road. I would hope it wouldn’t take a suicide, like it did for me, to go down this pathway,” Vance said.

Part of that work, he said, is figuring out how to fit mental health care into a day-to-day routine like any other kind of personal care.

“The hardest part is beginning,” he said. “Figuring out what the rhythm is to work out, what the rhythm is to begin to eat better, what the rhythm is to get into bed earlier so you can rest. Those are the little things that we can do — but in order for us to do that, we have to make a decision that that is what we’re going to do, that that is now going to be part of our lives.”

That work also requires starting small, Smith said, comparing making massive changes to how you approach mental health to attempting to walk a mile if you haven’t walked down the block.

“When we start to build new muscle with baby steps, what we start to find is we can do hard things, we can change the way we’re doing things,” she said.

Making a shift to treat mental health as an everyday consideration is an important step that could help care, said Dr. Christine Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center, during a separate interview.

Often, she said, she sees people come into the hospital seeking help only when they’re facing a moment of crisis, not as a preventive measure. That approach can complicate care for that patient and the system overall.

“What I’m seeing is we have a psych emergency room that is full, and people are sitting there waiting for days and sometimes weeks to be placed in an inpatient psychiatric unit; what I’m seeing is that people are presenting and engaging in mental health care at a state of crisis,” Crawford said.

Even after the delay to get a higher level of care following the emergency, patients are then discharged only to face long waiting lists to access a therapist for continued support.

That can mean that while the prevalence of mental health conditions remains about the same across racial and ethnic demographics, the severity of those conditions can be higher among Black communities, who are less likely to seek care, Crawford said.

The conversation was part of the Give Black Alliance’s series focused on “The Right to Be,” a theme that sprung out of the June Supreme Court decision that eliminated affirmative action in schools and the subsequent fight over diversity, equity and inclusion policies, said Bithiah Carter, the organization’s president and CEO.

The mental health segment of the serial conversations was called “The Right to Be Here,” and was meant to address a cultural landscape that too often sees Black men as a problem to solve, Carter said. She pointed to an African proverb that Smith uses in the book: “The lion’s story will never be known as long as the hunter is the one to tell it.”

“What I want to see is that the lions — Black men and boys — are not only claiming their stories, claiming their history, but leading where we need to go in the future,” she said.

Making life changes to take care of one’s mental health, Vance said, is a key piece of that goal.

“The question is, ‘Why?’ Why do I need to do that? Why is it important for me to take care of myself? Because I have a right to be here,” Vance said.

In Boston, mental health disparities for Black men persist. According to a Boston Public Health Commission report released in March, compared to men from other racial and ethnic groups, Black men faced some of the highest rates of persistent sadness in the city and some of the lowest rates of willingness to seek therapy during an emotional crisis. By neighborhood, residents in Mattapan were least likely to seek therapy during a crisis.

The field is hampered by a historical legacy that has left out or actively harmed Black communities, Crawford said. Early mental health workers in the United States in the mid-1800s identified the urge by slaves to run away as a mental health condition to be treated with whipping.

Later, early leaders in psychology and psychiatry made claims that Black people didn’t experience conditions like anxiety and depression because their brains weren’t sophisticated enough.

“That’s how the whole field of psychiatry started out,” Crawford said. “It was on a bad foot.”

She said those early roots and how the field developed from there often left Black communities with limited trust of mental health professionals and reduced care.

Over the decades, the field has seen only limited improvement, said Smith, who wrote a dissertation on mental health in Black men and boys for her doctorate in psychology.

That dissertation was 30 years ago, and she said she hasn’t seen things get better, and has maybe seen them get worse. She credits that in part to social media and the internet that make information about things like police violence and the death of Black men more open and easy to see.

Crawford said efforts like those from Vance and Smith to publish and publicize “The Invisible Ache” are important in pushing change around how mental health is viewed in the Black community.

“If we are normalizing conversations around mental health, hopefully that will make people feel as though there’s less of a concern that people are going to negatively judge them for having a mental health condition,” Crawford said. “Our idea of who the mentally ill is shifts when people who have lived experience are talking about that experience.”

Crawford, who has a background in child psychiatry, also said she thinks work to address mental health in Black communities needs to start early.

When she was a resident at Massachusetts General Hospital, she said, she had little interest in working with kids until she spent time working at the Nashua Street Jail. The first inmate she worked with was a man who had been involved in a fatal stabbing and had never interacted with a mental health professional before that day.

“The fact that I was the first mental health person he ever spoke to? It’s too late; he killed someone,” Crawford said. “If we’re able to intervene early on, we can reduce the number of Black men who are receiving their mental health supports for the first time in the criminal justice system.”

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide or is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.