Editor’s note: This story contains detailed descriptions of a racial terror lynching, which could be disturbing to some readers. We felt it was important to include these details to show the egregiousness of the injustice.

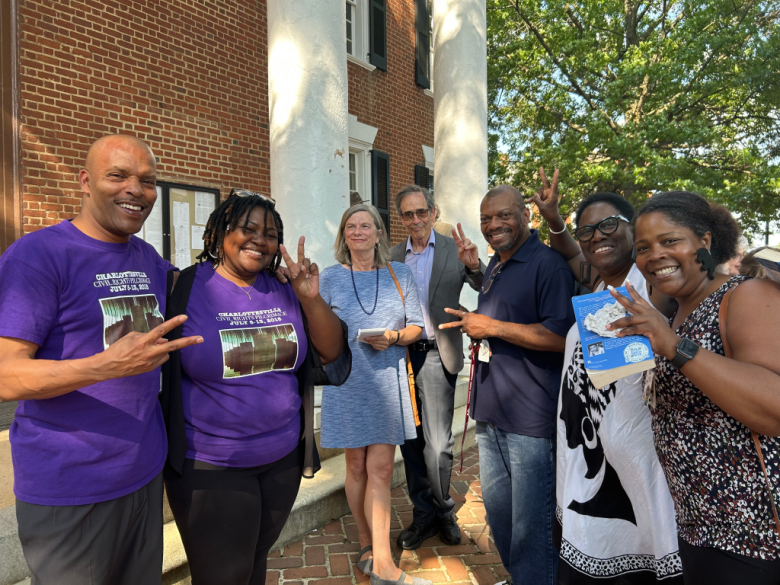

Wednesday afternoon, Melvin Grady got what he called a “very personal” birthday present.

July 12 is Grady’s birthday. It is also the anniversary of John Henry James’ death.

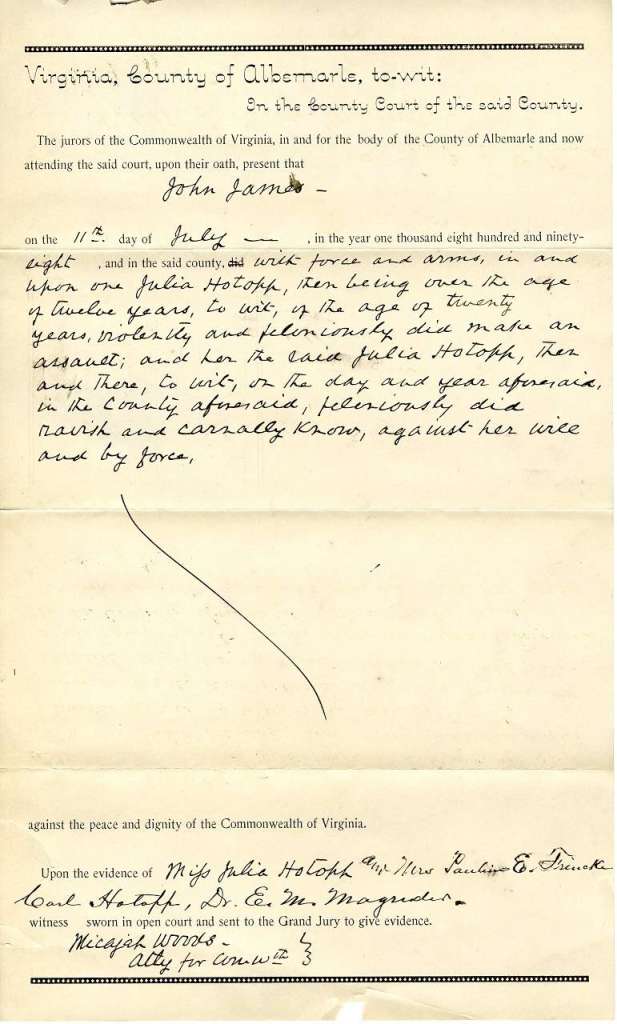

In 1898, James was lynched by an angry mob of white men because he was accused of assaulting Julia Hotopp, a young white woman from a prominent local family. After he was dead, a grand jury indicted him for the assault.

One hundred and twenty five years later, Albemarle County Circuit Court Judge Cheryl V. Higgins on Wednesday dismissed that indictment.

Higgins ruled that the grand jury not only improperly issued the indictment, it did so intentionally, making “a mockery of the judicial system.” The indictment was used “not as an instrument of justice, but as cause to lynch a man simply because he was Black,” Higgins said. “It was used corruptly, to sanction the lynching of John Henry James.”

“This is one little drop of justice,” said Grady, standing outside the Albemarle County Circuit Court minutes after the dismissal, a warm and steady breeze wicking tears from his cheeks.

Grady wore a purple t-shirt with an image of a memorial to James across his chest. Five years ago, Grady participated in a pilgrimage to collect soil from the site of James’ lynching and bring it to the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, where a glass jar of that soil is part of a memorial to victims of racial terror lynchings.

A lynching is the unlawful killing of a person, usually by hanging, by a mob. According to a report from the Equal Justice Initiative, attacks of lynching have overwhelmingly targeted Black people. Lynching was not considered a federal hate crime until last year.

The pilgrimage was emotional, Grady said. But the gravity of what that mob did to James, and what the United States justice system failed to do, hit Grady — who, like James, is Black — while he sat in the courtroom listening to the Albemarle County Commonwealth’s Attorney Jim Hingeley present the motion to dismiss the indictment.

“Knowing and traveling, I was fine. But here, it really hit me. I’m going back to imagine a guy who didn’t do shit — pardon my language — getting lynched, no evidence whatsoever,” Grady said. “I’m telling you, it’s powerful. I cried in there, hearing the testimony, the ruling. It was powerful. I feel honored to be a part of this.”

John Henry James’ story is an important part of local history, but it wasn’t really told until a few years ago, said Jalane Schmidt, an associate professor of religion at the University of Virginia and director of the Memory Project at UVA’s Karsh Institute for Democracy.

Even now, the story isn’t widely known, though historians, lawyers, and community members think it should be. It’s a difficult story to tell, in part because it is horrific and violent, and in part because the historical record offers inconsistent, and in some cases unreliable, reports and accounts.

James was accused of assaulting 20-year-old Julia Hotopp, a young white woman from a wealthy local family. Her father, William Hotopp, was the founder and owner of Monticello Wine Company — at the time the largest winemaking company in the country.

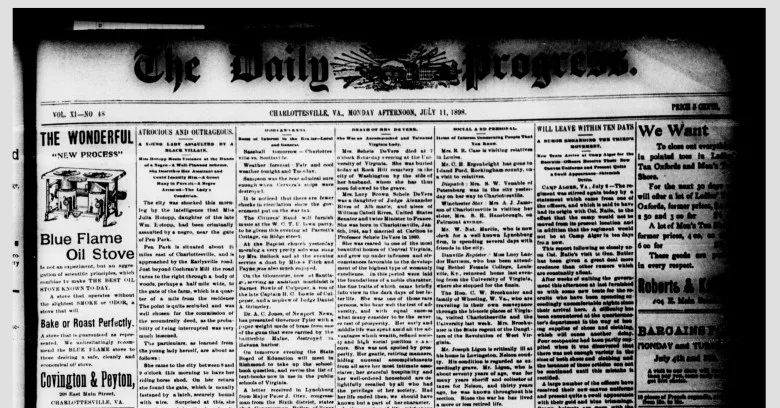

On Monday, July 11, 1898, the Daily Progress reported Julia Hotopp’s account of the incident. “Atrocious and outrageous,” the headline read. “A young lady assaulted by a black villain.”

According to the account, the assault took place between 9 and 10 in the morning, at the gate of Pen Park, not far from the Hotopp residence. Julia Hotopp had ridden her horse into Charlottesville earlier that morning to get the horse new horseshoes. When she returned home, the gate to the park was wired shut instead of fastened by its usual latch, and since there were no farmhands around, she dismounted to open the gate herself. Before she could remount, someone struck her from behind, grabbed her by the neck and forced her to the ground, where Hotopp said she became unconscious.

The Progress reported that Hotopp’s horse arrived back at the house without its rider, which alarmed Hotopp’s brother, who ran toward the gate and met his sister along the way. When the siblings met, Hotopp “swooned again.” Once back at the house, Hotopp “described her assailant as a very black man, heavy-set, slight mustache, wore dark clothes, and his toes were sticking out of his shoes.”

Hotopp then became unconscious for a third time “and was still in that condition, attended by several physicians, at last accounts,” the Progress wrote.

News traveled around the city quickly. People starting searching for the assailant and by noon, “a negro named John Henry James was arrested in Dudley’s barroom,” the Progress reported.

James “somewhat” met Hotopp’s description of her assailant, the Progress said. He was brought to jail “to await further developments.” Though, after James was arrested, people continued searching for possible suspects. “The country is being scoured by white and black men, and if the fellow is caught, and can be identified, we fear the worst,” the report ended.

That same report said that Hotopp “resisted the fellow to the extent of scratching his neck so violently as to leave particles of flesh under her fingernails and so effective was the resistance that he failed of accomplishing his foul purpose.”

Hotopp’s resistance, and her description of her assailant, was never referenced again.

By the next issue of the Progress, 24 hours later, James was dead, lynched by a mob before he could appear in court.

On July 12, The Progress printed a detailed report of what had happened earlier that day.

According to the Progress, a large crowd followed James to the jail upon his arrest, already threatening to kill him. As a result, authorities thought it would be best to “remove the prisoner to Staunton for safety,” and did so with some secrecy, the night of July 11. When people found out about this, they were “outraged,” the Progress reported.

That night, Albemarle County Court Judge John M. White issued a summons for a grand jury to meet at 10 a.m. the next day, on the morning of July 12. White did this “realizing that prompt and efficient means would have to be resorted to to calm the excited populace,” the Progress wrote.

Two hours before the jury met, at 8 a.m., James, Charlottesville Chief of Police Frank P. Farish, and Albemarle County Sheriff Lucien Watts boarded a train in Staunton bound for Charlottesville. “He [James] didn’t seem to give the officers any trouble, and when they boarded the train this morning, for Charlottesville, it was not considered necessary to handcuff him,” according to the Progress.

Reports show it was clear to everyone — including James — what was about to happen.

“The prisoner, as seen in Staunton on his way to the train handcuffed to an officer, was a pitiable sight,” the Staunton Record reported, as relayed in the July 13 issue of the Progress. He had a “look of fear upon his face” and was “shaking like an aspen leaf.”

“Several Staunton gentlemen who felt sure there would be a lynching got on the train and went to see it,” The Staunton Record said.

James did not make it to Charlottesville. A mob of about 150 unmasked white men waited for James’ train at Wood’s Crossing in Albemarle County, just four miles outside of the city — a usual stop for the train.

A group of about 40 Black men who’d heard about the plan ran to help James, but they were “outnumbered and forced to retreat,” according to the historical marker now standing near the Albemarle County Courthouse.

As reported in the Progress, when the train stopped, members of the mob boarded, resisting Farish and Watt’s attempts to keep them out of the car. They then restrained the lawmen (who later claimed they could not see and therefore could not identify the men who bound them from behind). The mob dragged James off the train, threw a rope around his neck, and led him to a locust tree about 40 yards away, near the blacksmith shop.

“He was asked if he wished time to pray,” the Progress reported. “Before God, I am innocent,” James reportedly said.

Then they hung him. The account is detailed by the Progress and re-published in other papers:

“The rope was thrown over a limb about three inches in circumference and that miserable wretch was drawn up. The limb jutted out from the tree at a sharp incline, so that the rope slid downwards toward the body of the tree, and when at rest the man’s body was almost touching the body of the tree. Under the tree was a bench, and his feet were only a few inches above it. As soon as he was elevated the crowd emptied their pistols into his body, probably forty shots entering it.”

The whole thing took just a few minutes.

James’ train had already left. Another passenger train passed the crossing as the mob lynched James, “forced witnesses of a lynching,” the Progress wrote.

The only person mentioned by name in any of the reports, other than the law enforcement officials and James, is Carl Hotopp, Julia Hotopp’s brother. The Progress reported that he “arrived about ten minutes after the hanging and emptied his pistol into the body.”

James’ body hung dead from the tree for a couple of hours, and in that time, hundreds of people visited the scene, “many of them gathered relics of the occasion, taking some portion of his clothing, etc,” the Progress wrote.

“When the mob dispersed they came away in any direction that suited them, some coming on to the city, others returning to their homes, all with a perfect indifference to any future investigation,” ended the Progress’ report.

The coroner’s jury issued its report the following day, saying James died either from the hanging or being shot, and that he “came to his death by the hands of persons unknown to the jury.”

J.H. Barcus, a Black man who worked for the coroner, removed James’ body from the tree and prepared him for burial. “I found thirty bullet holes in the body,” Barcus later said in the coroner’s inquisition.

James’ body was likely still hanging from the locust tree when the grand jury indicted him for Hotopp’s assault.

The jury heard of James’ death while in session. But they stated that they had reviewed the evidence and felt they had probable cause to issue an indictment on the charge of criminal assault upon Julia Hotopp.

It’s possible James wouldn’t have appeared before the jury, even if he had made it to the courthouse. The jury was sworn in when James was still on the train from Staunton, one hour before he was due to arrive. Micajah Woods, the commonwealth’s attorney at the time, “thought it unnecessary to introduce any other witnesses than the young lady and her sister, and the jury retired to their room to make their investigation,” according to the July 12 report in the Progress. (Woods served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War.)

Some reports make it seem like the officers wanted the law to take its course, that they didn’t tell the crowd who James was, that they pleaded with the mob to stop, to let the court decide whether James was guilty of assaulting Hotopp. Other reports, like one from the Waynesboro Herald, said that the rope was around James’ neck “in less than two seconds,” suggesting that the chief of police and the sheriff didn’t fight as hard as they said they did.

The conflicting reports don’t stop there. Though the Progress said that Hotopp could, and did, identify her assailant (as James), the Staunton Record’s report, as re-printed in the Progress, said otherwise:

“The information gleaned from the officers while they were in Staunton was to the effect that the lady had not recognized the prisoner as her assailant when he was brought before her, and that there was considerable doubt that he was the man,” the Record wrote.

Yet another paper, the Staunton News, said James admitted to the assault before the mob hung him, something other papers directly contradict. The Record also said that as the mob took over the train, “Woods [the commonwealth’s attorney] had said there would be no difficulty whatsoever to convict, as the evidence was conclusive.” Woods was not there, so it’s unclear how that message would have been relayed.

“This being so, the crowd thought there was no reason for the delay and they decided to lynch the prisoner,” the Record wrote. “The fact that there is no doubt of his guilt makes the people of Charlottesville heartily approve the lynching, as in this way the innocent is spared the terrible ordeal of being a prosecuting witness.”

In the days following James’ execution, the Progress published various letters to the editor that supported that very sentiment. One, taken from the Alexandria Gazette, said, “A negro was lynched near Charlottesville yesterday for the brutal crime of which such punishment is the prescriptive penalty in the South, and will continue to be, law or no law. The white men of Virginia will not, and never will, allow the negro outragers of their mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters the chance of escaping the law’s delays and quibbles, or subject their unfortunate victims to the mortification of a public trial.”

Letters published stating that James deserved a trial and scolding citizens for taking the law into their own hands were met with letters stating that it would be worse for Hotopp and other white women like her to have to re-tell their account to a jury, than for an accused Black man to be lynched.

Some papers asked questions. In its July 21, 1898 edition, the Staunton Spectator and Vindicator questioned why James’ law enforcement escorts “took the local train instead of the fast train to Charlottesville,” and why it “was not considered a material question before the coroner.”

The Richmond Planet, a weekly African American paper, covered James’ killing extensively in its July 16 edition. On its front page, it re-printed the Progress’ July 12 account almost word-for-word, with some small but significant changes.

The Progress used the headline, “He Paid the Awful Penalty: John Henry James Hanged by a Mob Today.” The Planet’s was, “They Lynched Him. A Colored Man Dealt With — Taken From Train. Died Protesting Innocence. A Brutal Murder — Mob Makes No Effort at Disguise.”

The Planet used the word “man” or “colored man” to refer to James, whereas the Progress had used “negro” or “the wretch.” It also had completely different titles for the different parts of the story. For instance, the Progress titled the section about the grand jury at Albemarle County Courthouse “A True Bill.” The Planet called it, “The Farce at Charlottesville.”

The Planet also omitted the Progress’ description of James, that he sold ice cream, was not a resident of Charlottesville but instead a “tramp” and that he had no family in the area.

The Planet condemned the lynching and blamed the authorities for James’ death. “The story of the brutal murder is revolting. We believe that the authorities were blamable. They knew that it was risky to bring this man unprotected to Charlottesville. James died protesting his innocence to the last. We do not believe that any effort will be made to punish the murderers. They boldly perpetrated the crime and virtually defied the commonwealth. There was no effort made to conceal their identity. The guilt or the innocence of James do not enter in the question,” The Planet wrote in an article titled “Another Virginia Lynching.”

The Planet didn’t stop its critique there. It also published “A Slight Comparison,” pointing out differences in how white and Black individuals are treated by the law.

A white mob lynched James, a Black man, for allegedly assaulting a white woman. Whereas “a white man who brutally assaulted a 12-year-old colored girl near Amelia C.H., Va., was given a brief time in the Virginia penitentiary, and during last month, upon the representations of his friends was pardoned.” Another white man who was found guilty of assaulting a child was “adjudged a lunatic” and sent to an asylum.

“If we are going into the hanging business, let us do it squarely and fairly,” the paper wrote.

James’ death by lynch mob was not unique, nor was it uncommon during this time. The Equal Justice Initiative has documented more than 4,400 racial terror lynchings in the United States during the time between Reconstruction (roughly 1863) and World War II (which ended in 1945).

And it wasn’t a secret. In its July 16, 1898 issue, the Planet published an article called, “The Reign of Lawlessness: Judge Lynch’s Bloody Work.” It listed the names of some of the people who were lynched, their race (mostly “colored,” but a few white), their charge (some have “none”), across the South from Jan. 5, 1897 to July 13, 1898, about a year and a half. “Total 202,” it reads.

This period was a turning point in Virginia history, Schmidt, the UVA professor and historian, said during Wednesday’s court proceedings, in which she presented evidence from the historical record, including many of the newspaper articles mentioned in this story.

The mob that killed John Henry James, the officers that allowed (or possibly incited) the mob to kill James, and the grand jury that issued a posthumous indictment of James, all violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, said Schmidt.

The Fourteenth Amendment, adopted in 1868 as one of the “Reconstruction Amendments” after the Civil War, grants equal legal and civil rights to African Americans, including those who had been enslaved. “Nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Virginia was readmitted to the Union in 1870, after it had ratified the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and adopted a new state constitution that received support from both Black and white citizens.

But by the time James was killed in 1898, white Virginians were tired of that constitution and the rights it afforded Black citizens, and pushed for another. They succeeded when, in 1902, Virginia adopted a new state constitution and began the rule of Jim Crow law — which legalized and enforced racial segregation — until 1970.

Writing in the Richmond Planet the week that James was killed, Planet Editor John Mitchell Jr. wrote that “the lynching of John Henry James will be far more damaging to the community than it will be to the alleged criminal. His troubles are o’er; those of the community have just begun.”

“We in this courtroom are that damaged community,” Schmidt said in her testimony Wednesday. More than 100 members of that community had filled both the courtroom and the upstairs jury room, together asking for “a modicum of justice” in the dismissal of the indictment brought against James.

The indictment is “a symbol of racial injustice,” said Albemarle County Commonwealth’s Attorney Hingeley, who brought forth the motion to dismiss it.

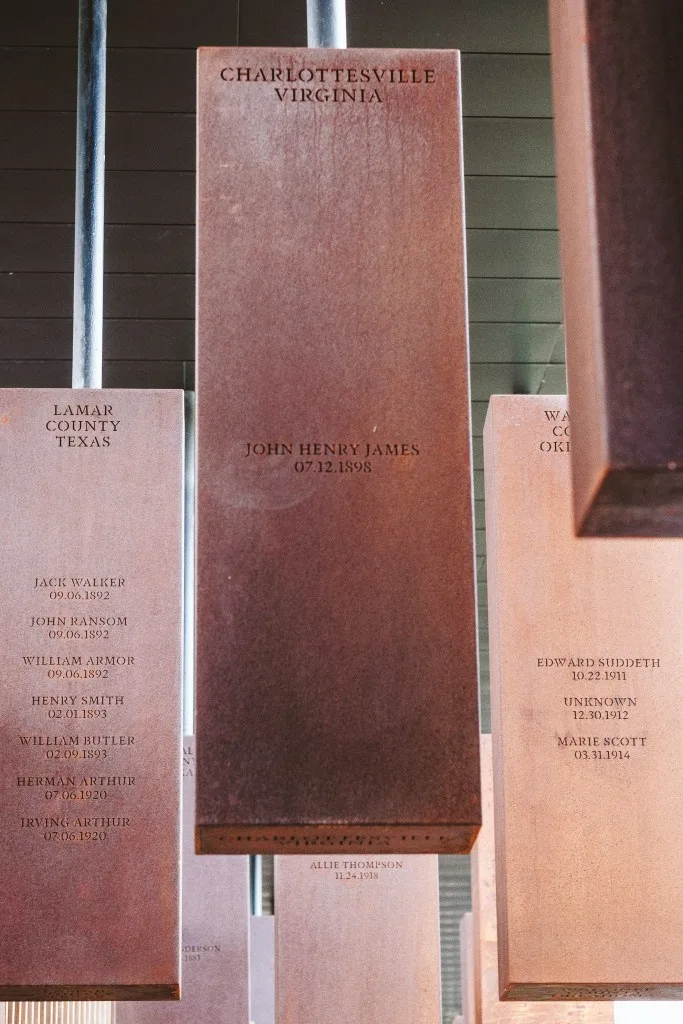

Hingeley was inspired to do so after visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice — colloquially known as the lynching museum — at the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, in April.

It’s the same memorial depicted on math teacher Melvin Grady’s t-shirt.

One of the monuments in the memorial represents Albemarle County, and John Henry James is the only name on it.

Hingeley returned home wondering what he could do. He thought of the indictment against James that remained on the record.

The indictment is “a symbol of racial injustice,” Hingeley said. In court, he argued that it was invalid because it was issued after James’ death, and knowingly so — the grand jury was aware that James was dead before it issued the document. (A dead person cannot be charged with a crime.)

Hingeley also argued that Commonwealth’s Attorney Woods did not have enough evidence to seek an indictment against James, anyway. If James had indeed matched the description Julia Hotopp gave of her assailant, if his neck had been covered in deep fingernail scratches from Hotopp’s resistance, that would have been documented in the historical record along with all of the other details present, such as the circumference of the branch (“about three inches”) from which the mob hung James’ body.

And, with conflicting reports of whether James confessed or maintained his innocence, there was “a great conflict as to what crime may or may not have been committed,” Hingeley said. One report said Hotopp fended him off. Another quoted Woods as calling it “the horrible crime of rape.”

“The evidence is what this prosecutor did not have,” Hingeley said.

At the end of his arguments, Hingeley made a few observations. One is that the court made no effort to bring the mob to justice. An official inquiry determined the crime was committed “by persons unknown.”

“And yet none of them masked,” Hingeley said.

Another is that the justice system was complicit in the lynching, “and the work the community was then engaged in, which was the work of white supremacy.”

When Judge Higgins dismissed the indictment — in a courtroom not far from the very spot where the grand jury chose to issue it — people broke out into quiet applause. Some wept, some hugged.

“Just one of many,” said a woman in the courtroom.

Outside, Don Gathers, a faith leader and activist, said he was having “mixed emotions.”

He was glad that James had received “some level of retribution and justice,” but was “sad that we even have to be here for this. This is just a very small pebble in a large pond. We can’t lose sight of the fact that, while we won this particular battle, the fight continues. This was a physical lynching, but the torment that is placed on Blacks, Black males, throughout history can’t be ignored.”

DeTeasa Brown Gathers held her husband’s hand as she said “rest in peace, John Henry James. And rest in peace to all that have been systemically lynched for the past 125 years, being wrongfully accused, being treated like this.”

They stood not far from a marker, placed outside the courthouse in 2019, commemorating James’ death, installed in partnership with the Equal Justice Initiative’s Community Memory Project.

Schmidt touched on a similar point. She said that the ruling is a reminder of the “evergreen” importance of the Fourteenth Amendment. “It’s never too late to right a wrong,” she said, and “this is a particularly egregious case from 125 years ago that’s still relevant today.”

There are still disparities in legal treatment of white people versus people of color, particularly Black people. For instance, Black people represent about 13% of the U.S. population, but account for 27% of arrests, according to a 2021 report by The Urban Institute’s Justice Policy Center. “Police are also more likely to use force and excessive force against people of color during police contact,” the report stated. Additionally, Black people are incarcerated at more than five times the rate of white people, the report said. At the end of 2019, Black Americans were incarcerated at five times the rate of white Americans.

“It’s a symbol of racial injustice,” Hingeley said of the indictment, and removing it from the record “is a small step.”

“We’re never going to be able to bring to justice the people who committed the lynching, or to restore John Henry James’ life that was so terribly taken from him,” he continued. “I don’t want to exaggerate and say that we’ve made a big step. But it’s a good step, and an important step. I hope that out of that will grow a sense of commitment and dedication to continuing the work of achieving racial justice here, because we have work to do.”