Good Will Hunting, by almost every measure, remains one of the most popular movies in American cinema. It currently has a 5/5 rating on Common Sense Media, a 97% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, which is based on more than 250,000 reviews, and it has amassed more than $225,925,989 in box office revenue.

Considering its popularity, it is not surprising that clinicians across disciplines have offered commentary on various aspects of the film, ranging from its portrayal of the therapeutic relationship and the impact of trauma on children, to the use of film as an effective teaching tool for clinicians. Like many therapists, one of my favorite scenes in the movie Good Will Hunting is the infamous “It’s Not Your Fault” scene between Will and Mark because it demonstrated what I have often witnessed in private practice: the power of therapeutic breakthroughs between a clinician and a client.

However, as a therapist who works mainly with Black men and boys, one of the most revealing scenes in the film is when Will skipped a job interview and sent his best friend as his replacement in the now famous “Retainer” scene. The scene was obviously hilarious, but it also conveyed profound differences in how race, mental health, and the criminal justice system interact in American society. Therefore, it is surprising how few commentators have pointed to three fundamental problems with Good Will Hunting: 1) The film essentially ignored the “mental health to prison pipeline,” which ensnares many males in the criminal justice system, particularly African American males. 2) The film downplayed the tremendous amount of trauma and suffering that men and boys are exposed to while in many prisons and jails in the U.S. 3) The film highlighted the stark contrast in the way that Black genius and Black intelligence are treated outside the criminal justice system. The lack of attention to these three areas has profound implications for the thousands of men and boys, particularly Black men and boys, who reenter society and are often more traumatized than before their incarceration.

First, the film effectively erased the “mental health to prison pipeline” when it chose to minimize how Will’s trauma brought him into consistent contact with law enforcement. This omission is significant because while we know about the “school to prison pipeline”, we don’t talk as much about the “mental health to prison pipeline. One of the main reasons why Good Will Hunting remains important is because of how it cast a light on how males experience and externalize trauma and how this leads to contact and conflict with authority figures. Will’s anger, aggression, and defiance, for example, could not be understood without understanding his history of trauma. The same is true for many males whose externalizing behaviors cause them to come in contact with law enforcement and who are often misdiagnosed with behavioral or personality disorders rather than mood or anxiety disorders — which is particularly true for Black males. Take for instance the “Kia Boys”, who range in age from as young as nine and 11 years old, who have been highlighted for stealing cars, crashing and dying in cities across the U.S. These behaviors are often thought of as just reckless or “boys acting badly”, but in reality, they mask histories of complex trauma and unaddressed grief. The lack of attention to how males experience and externalize trauma contributes not only to misdiagnosis, but also to a lack of understanding of why so many males end up in the criminal justice system.

Second, the film essentially ignored the tremendous amount of trauma that men and boys are exposed to in prisons and jails across the country when it refused to show Will spend any significant time incarcerated. As inmates, men and boys are exposed to constant physical and sexual violence, are entrapped by prison policies like solitary confinement that worsen preexisting mental health problems and create mental health problems when none existed prior, and inmates get the worst health care. Research has demonstrated that inmates are exposed to rates of physical violencecomparable to the amount of violence experienced by war veterans. The threat of rape in prisons is so urgent that states like Alabama, New York, and California produce educational videos on how to avoid being raped while incarcerated. Additionally, correctional practices like solitary confinement have a devastating impact on the mental health of inmates but are still used on adults and youth. Reports have shown that close to 30% of youth at Rikers were in solitary confinement, which is 23 to 24 hours spent in a cell by oneself. The impact of solitary confinement is severe.

Despite the tremendous amount of trauma men and boys are exposed to, inmates often get the worst health providers while incarcerated. A major 2019 study titled “Why Prisoners Get the Doctors No One Else Wants” found that one of the major problems in correctional institutions is that doctors with histories of serious medical errors or past records of misconduct are hired to work in prisons across the country, and they often continue treating patients even after prison officials are made aware of problems. The scale of potentially traumatic experiences (PTE) that we ask Black men and boys to forget or ignore is a testament to our refusal to acknowledge the amount of violence and victimization that happens to men and boys behind bars in this country.

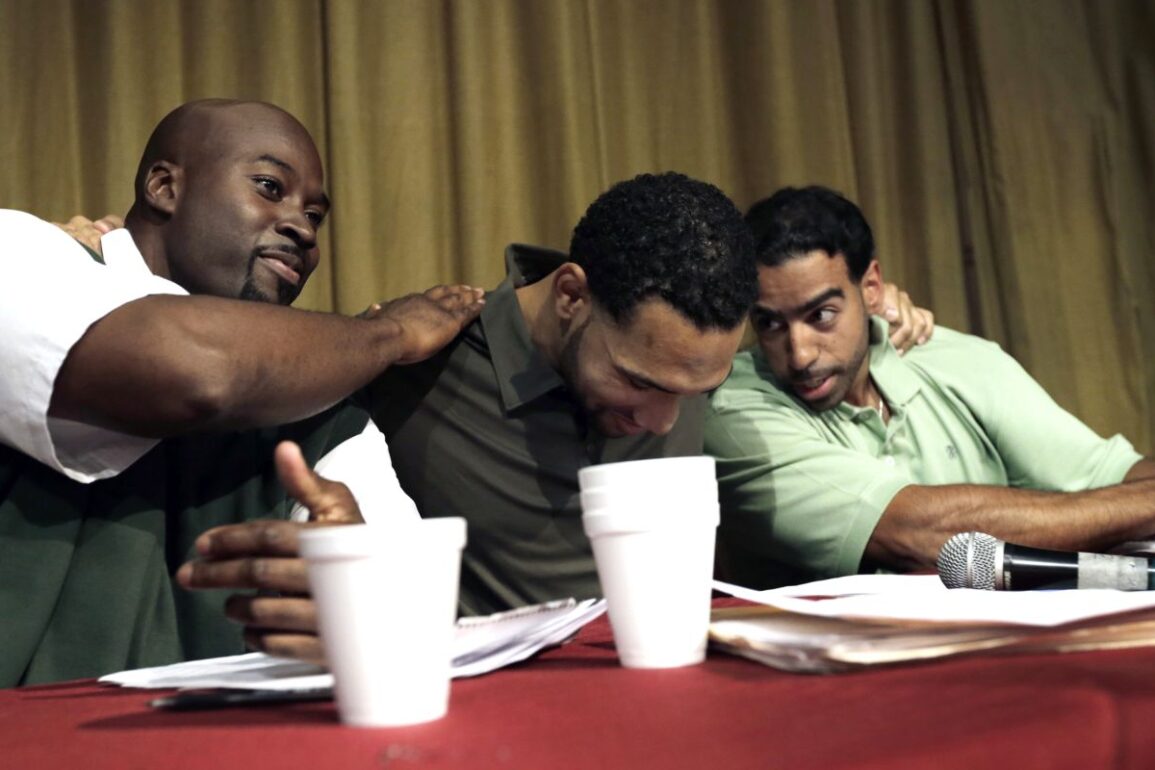

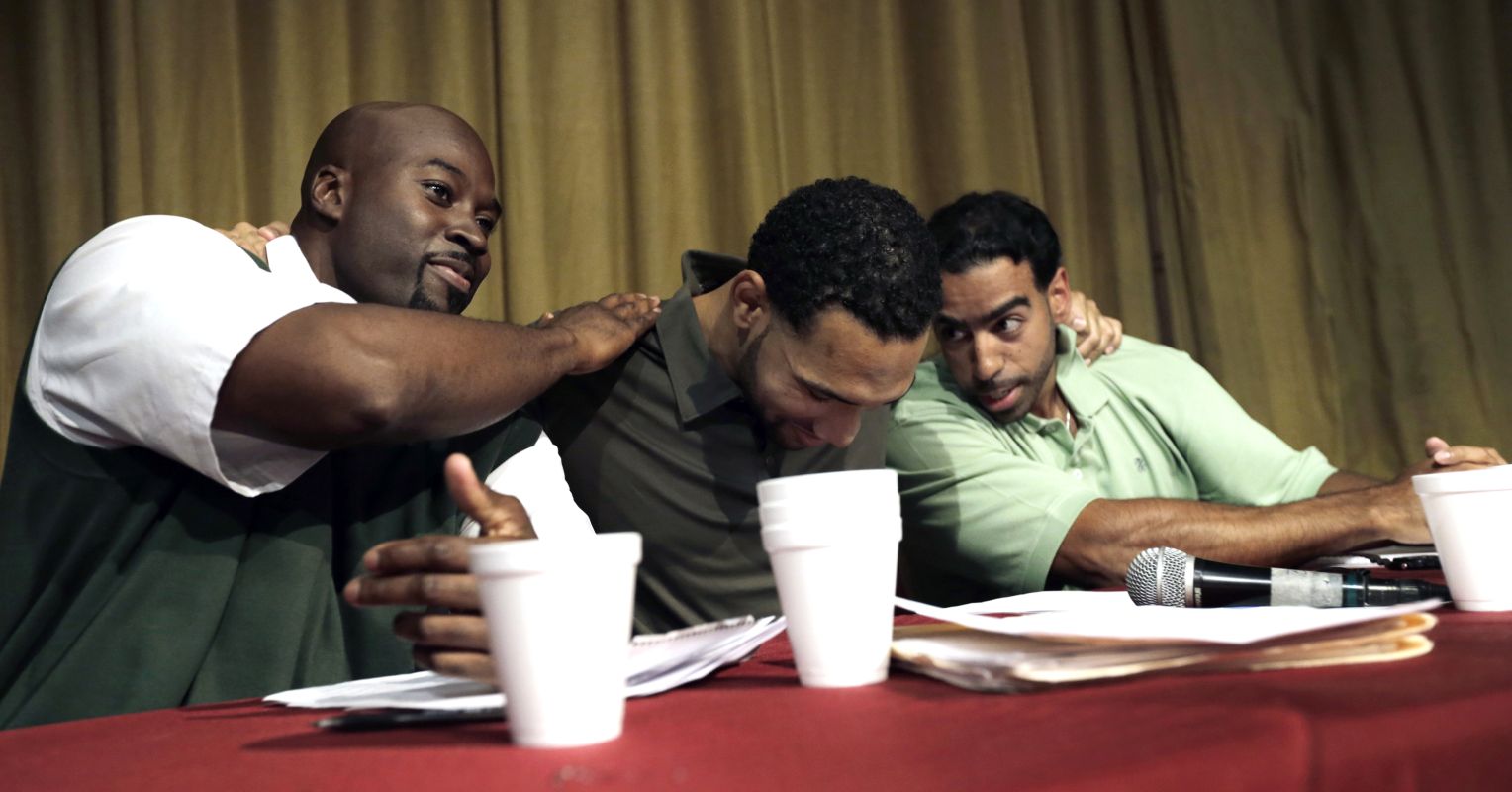

Third, by focusing exclusively on the relationships and opportunities made available to Will, the film highlighted a stark difference in the way that Black genius and Black intelligence are treated within and outside the criminal justice system. By the time Good Will Hunting was released in 1997, the criminal justice system in the U.S. had gone through several decades of transformation characterized by the mass incarceration Black men and boys. Therefore, it would be easy to point out that Black men and boys would not receive many of the privileges afforded to Will in the criminal justice system. For example, Black men and boys would not get parole after assaulting a police officer. Black men and boys also would not get to talk back and argue in court with judges and get their cases thrown out. And Black men and boys certainly would not get access to the best psychologist, psychiatrist, and therapist to assist them as part of the terms of conditions of their parole. One could certainly argue that Will is a fictional character so these privileges would not extend to any males regardless of race. However, one could not argue that Black genius and Black intelligence do not hold nearly the same promise and potential as it does for White males. The Mark of a Criminal Record study, for example, demonstrated that Black males with no felony record are less likely to be called for a job interview than white males with a criminal record. To be young, gifted and Black does not translate into promise and prosperity like it did for Will. The iconic picture of the three black male prisoners embracing each other after defeating Harvard’s debate team symbolizes the lack of opportunity for Black genius in America, echoing the unrealized dreams of Black men and boys in Maya Angelou’s poem, “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings.”

Despite its limitations, Good Will Hunting remains an important film because it opened the door to a discussion about how men experience and externalize trauma. However, the film’s decision to not deal with male trauma within the criminal justice system reminds me of how the film is rooted in fiction and not facts. The reality is that men and boys of all racial and ethnic groups who reenter society after incarceration not only face collateral consequences in employment, housing, and other structural-related barriers, but they also reenter society after being exposed to a tremendous amount of trauma and unaddressed grief that makes re-entry and regulation difficult. Black men and boys, in particular, face these challenges along with additional burdens due to racism. To eradicate the mental health to prison pipeline we must stop criminalizing the way men and boys experience and express mental health issues, end correctional policies that exacerbate and worsen mental health issues, and provide ex-offenders with culturally responsive behavioral health services when they reenter society. Only then will the redemption story of Good Will Hunting apply to all gifted and traumatized males, not just white males.