Jesse Van Tol is president and CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, an organization promoting racial economic justice policy.

Should the U.S. government pay reparations for slavery? That question dominates the long-running discussion about righting centuries of wrongs committed against Black Americans. But there is one injustice that Congress can — and should — act on right now.

After the Civil War, the federal government took many steps to accelerate the social, political and economic development of formerly enslaved people — including establishing a bank specifically for Black Americans liberated by the Union Army.

The Freedman’s Savings and Trust Co., known as the Freedman’s Bank, was chartered in March 1865. Any formerly enslaved person or descendant of one could open an account with a minimum deposit of a nickel, and any account with a dollar or more in it (about $20 in today’s money) would earn interest.

The bank was a key economic pillar in the broader project of Reconstruction across the postwar South. And like the rest of the project, it would curdle and crumble within a few years.

Many tragedies of the era featured overt violence. White supremacists, sickened by the sight of freed Black people gaining entry to the American Dream, launched a bloody and successful crusade they termed “Redemption.” Just a dozen years after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, every treasonous state was once again run by white power and every Black person within them was once again subjugated by people ready to murder them if they complained.

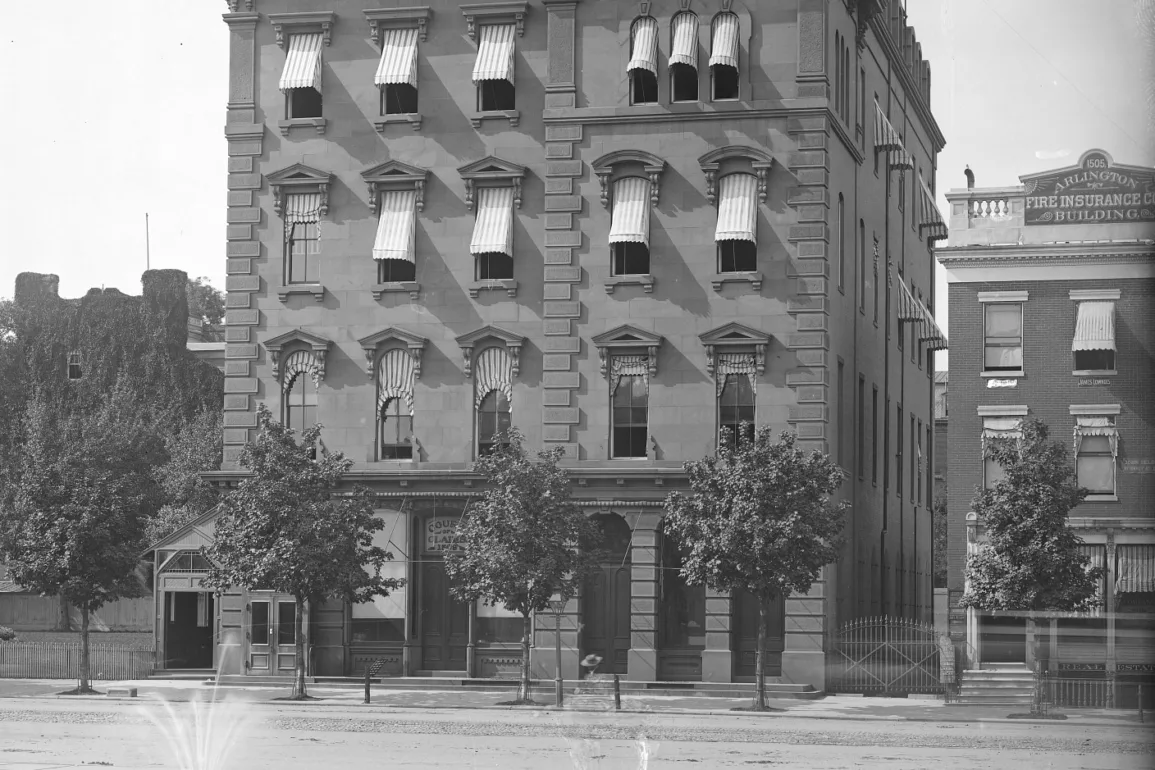

The tragedy of Freedman’s Bank was categorically different. No one raised a fist, let alone a mob. What happened to the bank was years of fraud and abuse that eventually collided with a complex economic shock. The bank, whose trustees were all White, lobbied Congress to loosen its charter, spent a sizable chunk of its total assets to build a grand headquarters, loaned depositors’ money to trustees’ friends without collateral, and concentrated its investment portfolio in speculative real estate and railroad lending. The Panic of 1873 finished the job the trustees’ malicious self-dealing had begun — though not before the same trustees lured Frederick Douglass to lend them his reputation by becoming president, a decision he’d later describe as like being “married to a corpse.”

The same deposit cards that had in 1865 promised Black families generational financial progress became worthless on June 29, 1874, when the bank ceased operations. Few of its customers would ever see any of their money again, and almost none saw all of it.

Determining how to compensate Black people for the many even more infamous ways this country has brutalized them can be complex. Congress should build upon the House Judiciary Committee’s historic April 2021 vote to advance legislation establishing a congressional commission to study reparations for slavery.

But the Freedman’s Bank fraud requires no study. We know exactly how much money we owe — and whose descendants we owe it to.

The bank’s meticulous records were perfectly preserved. We know the names, ages, occupations and family members of Freedman’s Bank depositors. The documents are so detailed and extensive that they have become a cherished resource for genealogy researchers.

Tens of thousands of Black depositors had roughly $3 million in the bank’s custody when it failed. In today’s dollars, adjusted for inflation, that’s about $77 million. Factor in 150 years of interest that Freedman’s Bank depositors were promised they could earn, and we’re talking somewhere between $118 billion and $139 billion, even under a conservative 5 percent annual return.

The government may not have directly owned and operated the Freedman’s Bank. But it cannot claim that it bears no responsibility for the conduct of the bank’s White trustees. Congress granted those men a bank charter, put itself rather than bank regulators in charge of supervising those men, and sent them south to make promises in the government’s name. Lots of people believed those promises. Few of them got anything at all back for their faith, and most never saw a cent.

Congress created this calamity. Congress should fix it.

Imagine for a moment how different our world might be if Black people possessed $118 billion more in wealth today. Imagine how the free flow of that accumulation might have reshaped history. Would economically and politically empowered Black communities have fought off the intentional destruction of such thriving Black neighborhoods as the Rondo in St. Paul, Minn., or Charlotte’s Brooklyn and McRorey Heights? Would the government have been able to get away with decades of the targeted disinvestment known as redlining?

We’ll never know. But what we do know is plenty to make a righteous choice. We can take a mathematically precise and morally unassailable course of action. Tough conversations about how to properly compensate for all this country’s other conscious wrongs done to Black citizens must continue. We can and should pursue answers to complex questions about how many 2024 dollars it should be worth to have lost a home and business to a highway construction project in 1959 or a life to a Klan massacre in 1910.

But let’s see some action, too. Let’s make that $120-odd billion down payment toward economic repair. Let’s find room for that morsel of justice in our multitrillion-dollar annual budget. Let’s see the federal government make reparations for the Freedman’s Bank. Let’s ensure that the heirs to those broken promises are made whole – with 150 years’ interest.