A New York philanthropist who donated $3 million to the last three living survivors of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre called on other wealthy white Americans to contribute to reparations, citing the lack of action from states and the federal government.

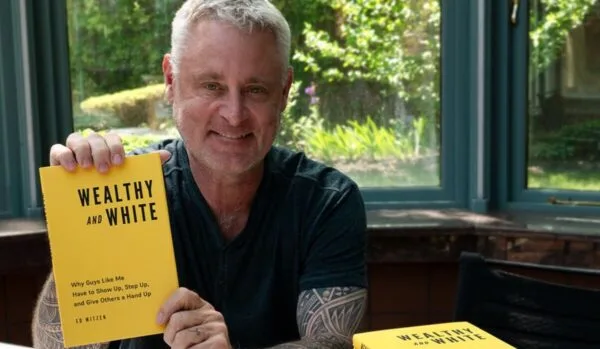

Business for Good founder Ed Mitzen, author of “Wealthy and White: Why Guys Like Me Have to Show Up, Step Up, and Give Others a Hand Up,” told CNN this week he was deeply moved by the ongoing legal plight of the aging survivors, leading him to put up his own money in 2022 to help the survivors, while he criticized public officials in Oklahoma for slow-walking compensation efforts.

“It just made me angry,” Mitzen said, explaining his motivations to the network.

“I was sitting there thinking what happened to them was irrefutable, whether or not it happened 102 years ago, or two years ago — it happened. It’s undeniable. And it felt to me like the government out there was trying to run the clock out on these folks.”

Two years ago, Mitzen’s New York-based nonprofit Business for Good donated $1 million to each of the survivors, while no federal, state, or local government entities have ever paid any money to the descendants of Tulsa victims, whose entire livelihoods were wiped out 100 years ago.

The last survivors — Viola Fletcher, 109, Lessie Benningfield Randle, 108, and Hughes Van Ellis Sr., who died in October at age 102 — filed their initial reparations lawsuit in 2020, nearly a century after their neighborhoods were incinerated, and their family members and neighbors murdered in one of the worst episodes of racial violence in U.S. history.

Modern courts have persistently denied any payout to the descendants due to the long time that has passed since the massacre, as demonstrated in 2005 when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a reparations appeal from Tulsa victims.

No other domestic nonprofit entity has ever stepped up on reparations in a big way like Mitzen’s has, with many conservative lawmakers wanting to turn the page on the country’s racist history.

Mitzen said reparations are not just a Black issue but an American problem to solve.

“I think that many folks fear that if other people rise up that they’re gonna somehow get pushed down. And it’s not a zero-sum game. If we can get everybody up the curve, we’re a much better country for it.”

Mitzen expressed hope that his philanthropic efforts would inspire others to give, emphasizing that white people had a moral obligation to acknowledge past injustices and to actively support marginalized populations through charitable investments.

“And I truly believe that it’s our responsibility in the white community to look at ourselves and look at the advantages that we’ve had and try to give those same advantages to other people that have been left behind.”

More than 20 years ago, Tulsa commissioned a study that determined more than 1,000 homes and businesses were destroyed as the Black financial district was ransacked, while the financial toll of the damage was estimated at $27 million in today’s dollars.

But when that 2020 case was re-examined through the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, it was too late as the statute of limitations had passed for survivors to file a lawsuit against the state of Oklahoma.

A new reparations lawsuit was filed in March 2021 and proceeded for more than two years before it was dismissed by a lower court last summer, prompting the appeal currently before the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

The civil action names the city of Tulsa, the Tulsa County sheriff, county commissioners, and the Oklahoma Military Department as defendants. The case was dismissed by a Tulsa County district judge in July 2023, setting up arguments before the state’s highest court on behalf of the plaintiffs, who are all more than 100 years old.

“It is a huge victory for us,” said Damario Solomon-Simmons, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, who spoke to The New York Times. “It allows us to move the case along as quickly as possible.”

Previously, District Court Judge Caroline Wall allowed the lawsuit to move forward in May 2022, but she dismissed the case in July 2023 after attorneys for the city successfully argued that “simply being connected to a historical event does not provide a person with unlimited rights to seek compensation from any project in any way related to that historical event.”

Wall made the ruling despite the appeal noting the advanced ages of the plaintiffs while asking the court to give the survivors an “opportunity — before they die and there are no other survivors of the Massacre — to take the stand, take an oath, and tell an Oklahoma court what has happened to them, their families and their community.”

The ruling by the state’s highest court will ultimately determine whether the case is sent back to Judge Wall for trial.

The lawsuit claims violations of Oklahoma’s public nuisance law, arguing that the legacy of the massacre still impacts the Black community after more than a century, and they should “recover for unjust enrichment” others gained from the “exploitation of the massacre.”

“We believe we should have a right to go to trial because we can prove that the nuisance is still continuing,” Solomon-Simmons told the Times, comparing Tulsa’s dark chapter to an oil spill.

“That oil is still in the water; it’s still polluting the water,” he said.

Previously, assistant Oklahoma Attorney General Kevin McClure disputed the claims in the current lawsuit, asserting that they were “premised on conflicting historical facts from over 100 years ago” and that the plaintiffs “failed to properly allege how the Oklahoma Military Department created an ongoing ‘public nuisance.’”

The massacre took place on May 31, 1921, after a white mob falsely accused a young Black man of assaulting a white woman, leading to a confrontation that quickly escalated to bloodshed.

The white mob, helped by the National Guard, attacked Greenwood, a prosperous neighborhood in Tulsa known at the time as Black Wall Street, and set it on fire.

As many as 300 Black citizens were killed, and hundreds more were injured as about 1,000 families were left homeless amid the ruins of what had been one of the most profitable districts in the Midwest at the time.

In the years that followed, public officials sought to expunge any references to the massacre in the city’s historical record, while the survivors and their families never received a dime in compensation from the city or the state.

“For that in and of itself, a trial must happen here,” Solomon-Simmons said.

The topic of reparations remains a hot issue among Democrats amid the 2024 race as President Joe Biden faced growing criticism for not taking any meaningful actions on reparations since he took office more than three years ago.