On October 15, 1964, Malcolm X addressed the Kenyan Parliament. Before he left for Africa, Malcolm addressed a Harlem rally and asked his followers to form “Mau Mau” groups in New York to liberate the Blacks.

“As I mentioned today – what we need in this country (and I believe it with all my heart, and with all my mind, and with all my soul) is the same type of Mau Mau here that they had over there in Kenya. Don’t you ever be ashamed of the Mau Mau. They’re not to be ashamed of. They are to be proud of. Those brothers were freedom fighters.”

During his Kenyan visit, he once more praised Mau Mau and argued that White America would never voluntarily give Black Americans freedom unless they were forced to do so. Malcolm X defended Mau Mau’s target of loyalists and supported the elimination of those standing on the way to freedom. Those who were killed for supporting the colonial regime included Chiefs Waruhiu Kungu and Nderi Wang’ombe.

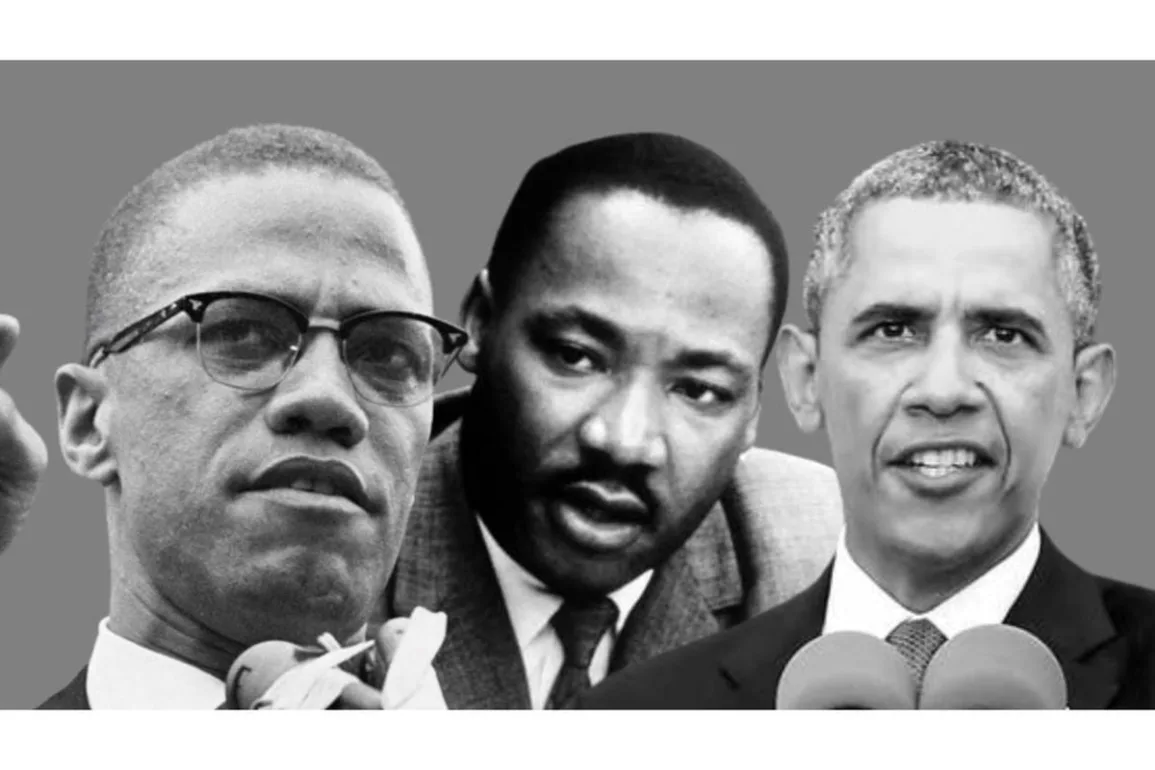

“In Kenya, the Mau Mau were revolutionary; they were the ones who brought the word ‘Uhuru’ to the fore… they believed in scorched earth, they knocked everything aside that got in their way, and their revolution also was based on land, a desire for land.” Malcolm, unlike Martin Luther King Jr, was not a proponent of a nonviolent approach to resolving the race question. Instead, he advocated for a “any-means-necessary” approach.

His 1964 speech has always been cited: “We want freedom by any means necessary. We want justice by any means necessary. We want equality by any means necessary.” He also felt that there must be alternative approaches in ending brutality against the Blacks. “We need a Mau Mau. If they don’t want to deal with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, then we’ll give them something to deal with. If they don’t want to deal with Student Nonviolent Committee, then we have to give them an alternative… give them a choice between this or that.” Thus, Malcolm did not leave the door of a violent approach towards liberation locked. “Malcolm’s transnationalism is still alive in the slums of Nairobi,” Kenyan historian, Mickie Mwanzia Koster, argued in a 2015 paper on Malcolm X and Kenyatta.

The realization that the Blacks in the diaspora faced the same predicament as their African counterparts had informed the Pan-African movement and led to its transcontinental growth. Figures such as George Padmore, immortalised in Nairobi’s George Padmore Street, was a key figure in influencing Pan-African leaders such as Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, Nnamdi Azikiwe, and Kwame Nkrumah – especially in establishing of anti-colonial networks. He believed that African liberation should be more than a flag and an anthem, and he stressed the radical transformation of society.

That mantra would later be picked in Kenya by the late J.M. Kariuki who argued for a transformation of the Kenyan society into a nation: “It takes more than a National Anthem, however stirring, a Coat of Arms, however distinctive, a National Flag, however appropriate, a National Flower, however beautiful, to make a Nation.”

Other figures with profound influence were W.E.B Dubois, Booker T. Washington, Marcus Garvey – the Jamaican activist who changed black politics by mounting a back-to-Africa movement in the 1920s – and Trinidadian Marxist intellectual and essayist C.L.R. James.

These, among others, laid the foundation that would later culminate in the global black liberation movements. Others who took the mantle from there included civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr and Thurgood Marshall.

Dubois would become an influential figure in the organisation of Pan-African congress meetings, which would be the turning point of African politics. Kenyatta would help organise the 1945 meeting in Manchester which was a launching pad for his return to Kenya after his 16-year sojourn. The Black American figures would also be influential to the likes of Tom Mboya, the Kenyan trade unionist and politician. Mboya, with the help of these black Americans, managed to raise funds to sponsor Kenyan students to join US colleges and universities. He contacted black elites, including Harry Belafonte, Jackie Robinson, and Sidney Poitier, for help.

As a result, Mboya coordinated the “airlift” of the first 81 Kenyan students the US. Later on, Mboya was hosted by Martin Luther King, and he requested financial assistance for some more students. He would also write a plea published by the New York Times on November 8, 1959, in which he laid out his philosophy: “Nothing constitutes a greater contribution to the struggle against poverty, disease and political subjection in Africa more than the contribution made toward our peoples’ educational advancement.” That led to the birth of the African-American Students Foundation, which raised sufficient funds to cover Kenya’s student’s travel expenses. The success of this project, mostly credited to Mboya and JF Kennedy, was also due to the linkages created by Dr Julius Gikonyo Kiano, who had approached his supervisor, Prof Robert Scalapino, seeking assistance to take African students to the US.

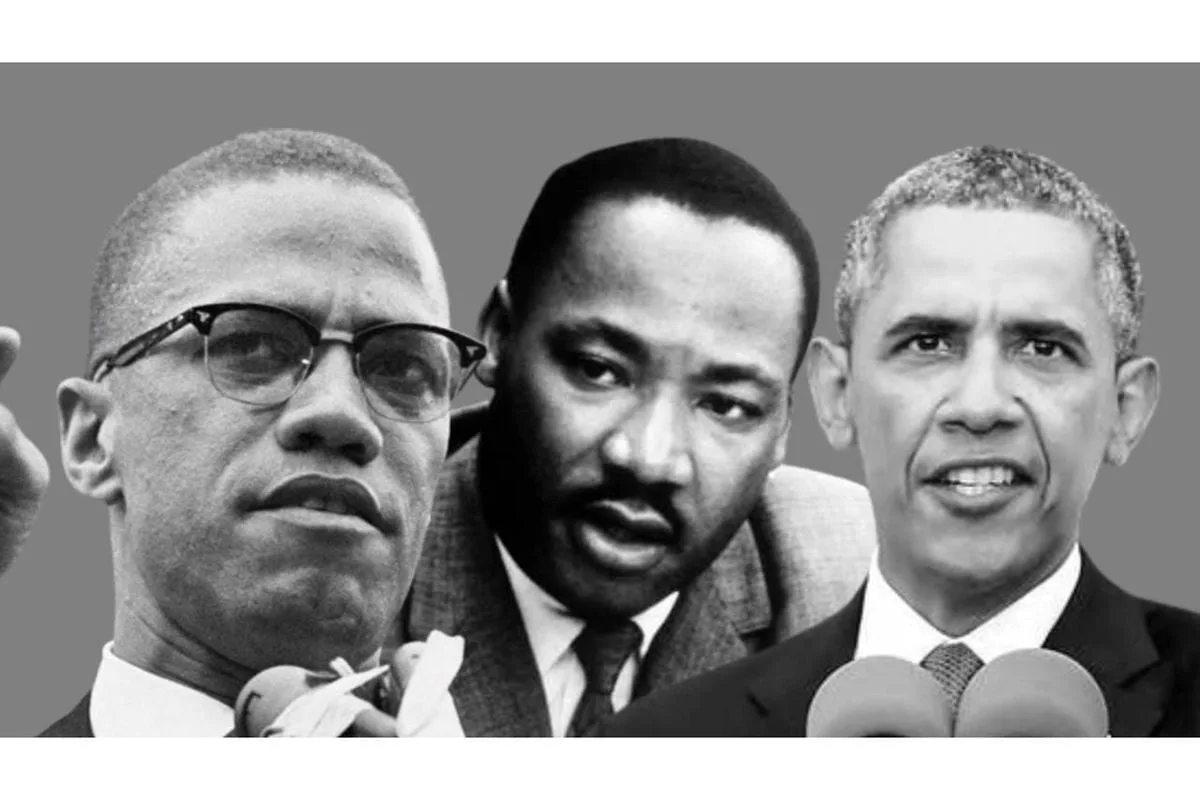

It was part of this awakening of Western education that would see many Kenyans leave. While the airlift had a profound effect, other students (not part of the Mboya airlift) would leave a legacy. Among these was Barack Obama Snr, the father of former US President Barack Obama.

Mboya, who attended Ruskin College, Oxford, wanted Kenyans adequately prepared for a post-colonial Kenya. There was a major shortfall in the number of graduates, so he set up a scholarship fund that would take young, bright Africans to the US and Canada. The beneficiaries included the Nobel Peace Prize winner, Prof Wangari Maathai, plus many senior government officials and technocrats.

Other great contributions across the border were the help of Thurgood Marshall, the civil rights lawyer and later US Supreme Court judge, during the Lancaster conference as Kanu’s advisor. By immersing himself in the Constitution writing of a post-colonial Kenya, Marshall did not want the new Kenyan constitution to fall into the trap of the American constitution, which he argued embraced slavery.

“In Kenya, as he saw it, he could start from scratch and get it right from the start,” wrote his biographer, Mary L. Dudziak. He had previously partnered with Mboya, who had developed linkages with labour union leaders such as Walter Reuters of the United Autor Workers Union and A. Phillip Randolph, the President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

All these – and many others – profoundly influenced how the blacks visualized their place in the struggle for freedom and their rights. Marshall told Dr Kiano during the Lancaster conference, “You’ve got to have a Bill of Rights in that constitution.”

By bringing Marshall on board, a minority in the US, they “reassured other groups that minority rights were central”. It was Kenya’s contribution to how such rights were negotiated. From violence, education, and constitution-making, Kenyans and their African diaspora counterparts have had much to share and remember during Black History Month.