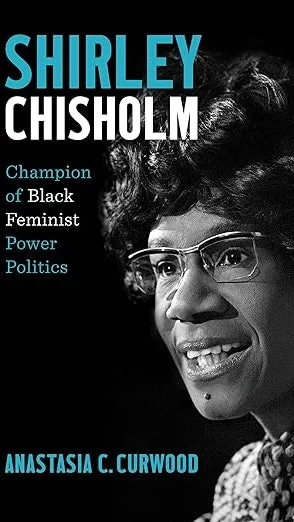

Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics by Dr. Anastasia C. Curwood (The University of North Carolina Press) is a fascinating and timely book that traces the political trajectory of the first African American congresswoman who would later break barriers as the first Black major party presidential candidate..

As we celebrate Black History Month, a close examination of Shirley Chisholm’s rise in progressive politics is not only important, but it is necessary. Chisholm paved the way for the Rev. Jesse Louis Jackson’s historic presidential runs in 1984 and 1988 and the election of a virtually unknown political figure — Barack Obama — in 2008.

Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics by Dr. Anastasia C. Curwood was published by The University of North Carolina Press.

Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics by Dr. Anastasia C. Curwood was published by The University of North Carolina Press.

Curwood, an associate professor of history and director of African American and Africana Studies at the University of Kentucky, introduces readers to a young Chisholm — not the feisty politician that she would become or the elder stateswoman that would mark her later years. The daughter of Caribbean parents, Curwood points out that as a young girl, Chisholm — who was born Nov. 30, 1924, in Brooklyn, New York — was deeply influenced by Eleanor Roosevelt and educator and civil rights leader, Mary McLeod Bethune.

“Late in life, Chisholm would credit Roosevelt, Bethune, and her grandmother Emmeline Seale as the three women who had the most influence on her,” writes Curwood. “Bethune and Roosevelt shared with Chisholm the belief that the government ought to work in the service of the people, including women.”

That kind of advocacy would guide Chisholm’s own advocacy across the years as a New York assemblywoman and later as a congresswoman. Along the way, Chisholm developed what Curwood describes as “Black feminist power politics” that would define much of her career. In addition to supporting a progressive political agenda that included championing antipoverty and antiracism programs, she prioritized support for women’s issues such as abortion rights.

“Chisholm’s years in the assembly were also the beginning years of the so-called second wave women’s movement,” notes Curwood, who brilliantly parallels Chisholm’s life with the social and political movements of the day. “It was through the women’s movement that Chisholm would raise her national profile.”

While many political observers rightly point to Chisholm’s historic breakthrough as a Black woman political candidate, what is often overlooked or ignored completely is the way in which she leaned into and embraced feminism. That’s why Curwood’s book is so important. Given the sexism that abounded within the burgeoning civil rights movement of the 1960s, Chisholm’s advocacy for women’s issues made her a natural target of critique not only from white observers but Black from men.

The gift of Curwood’s book is that she takes readers on a journey, introducing us to Chisholm before she became a household name in American politics. In providing an historical timeline of Chisholm’s rise, Curwood painstakingly helps readers to understand Chisholm’s own evolution. Her radical politics and embrace of Black feminism developed and evolved over time. Still, as Curwood notes, Chisholm’s “Black feminist power pragmatic approach — democratic and collaborative — makes her work difficult to find in the archival record.

“Her effectiveness as a legislator would come not so much in the form of sponsoring bills and passing her own legislation,” writes Curwood. “Rather, her strategic handling of committee work and legislative procedure laid the groundwork for later successes, and solved problems without fanfare.”

In addition to her historic run for president in 1972, Chisholm’s legacy rests in the number of Black women leaders whom she would mentor, most notably Congresswoman Barbara Lee of California.

“Chisholm is increasingly invoked as a symbol of universal access to economic and political power,” writes Curwood. “Despite her existence in a body that did not confer birthright power within the United States, Chisholm understood how to wield political power.”

Despite the enormous gains that Black women have gained in politics and beyond, the recent attacks on Dr. Claudine Gay at Harvard University and the attacks on Black women in all sectors of society illustrate that we have a long way to go before we fully can say that we’ve actualized Chisholm’s vision. It is no coincidence that after leaving Congress, Chisholm joined academia where she taught at Mount Holyoke College — a private women’s liberal arts college in Massachusetts.

“Her priorities carried immense resonance in her time as an extension of Black Power and feminism, but they also do in ours,” warns Curwood. “As we confront white supremacist oligarchy and kleptocracy in the twenty-first century, marginalized Americans are looking for ways to deploy our own power on behalf of democracy. Chisholm’s life is one road map — or perhaps a North Star — for those who would use politics to recommit the nation to freedom, equality, and justice.”