The city of Boston has taken up the monumental task of trying to heal the racial inequalities caused by 400 years of slavery. Two years ago, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu, created the Task Force on Reparations. Its aim is to understand the history of enslaved people in Boston and the impact on their descendants today.

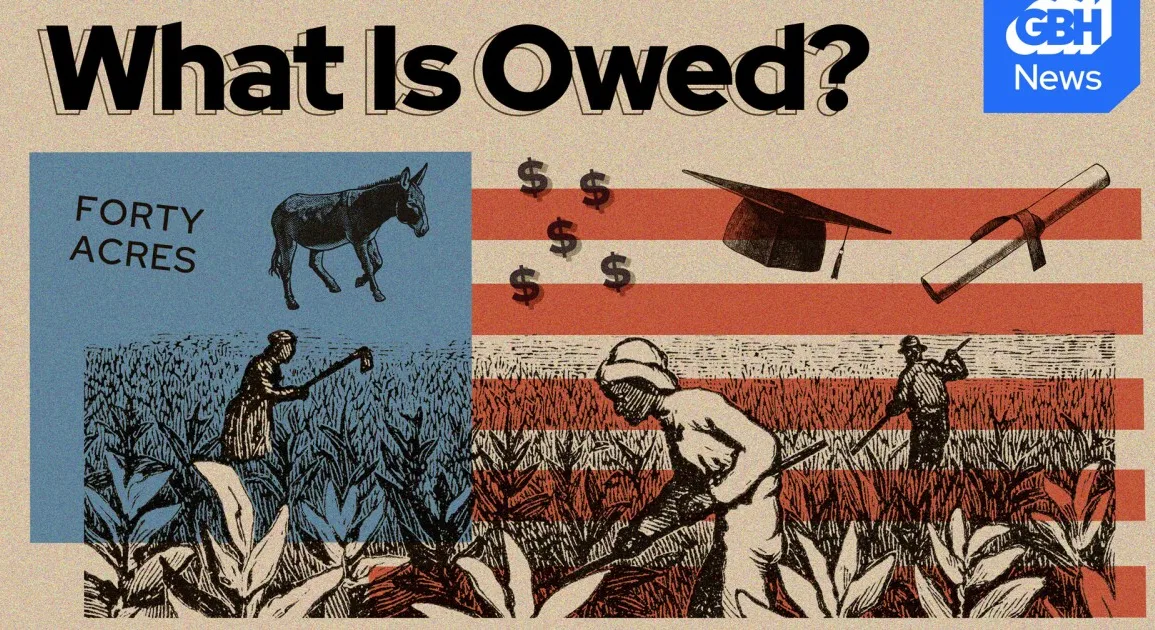

As the city wrestles with the idea of paying reparations to the descendants of enslaved people, a new seven-part podcast premiering tomorrow by GBH and PRX called “What Is Owed?”is taking a look through Boston’s layered history and the questions that will inform what reparations might look like in one of America’s oldest cities. GBH’s All Things Considered host Arun Rath spoke about the show with its host, GBH News political reporter Saraya Wintersmith. What follows is a lightly edited transcript.

Rath: This is great work and so excited to have you to talk about it. Let let’s dig in, because Boston has so many dark moments in its history regarding slavery. It’s here that slavery was first legalized in colonial America. It’s also one of the first places to start looking into the topic of reparations, and even saw a bill setting up a framework for it going back to the 1980’s. What can you tell us about that and how it’s informing the reparations conversation right now?

Wintersmith: Yeah, it’s been really eye opening in a lot of ways for me to particularly, when I think about Boston and its relationship to slavery and it being part of colonial America. In one of the interviews with a historian that appears across the podcast, a person said to me that someone had to have seen the practice and recognized that it was something that needed to be protected and insured and maintained. So it’s the beginning of what perpetuates this horrible system for years to come. Just to start with that, in the podcast, we definitely talk about Boston’s dark moments, but it really is also an exploration of Blackness and history and politics, because the issue wraps all of those things up into it.

Rath: Well, that’s one of the things I love about the approach to this narrative is that, in not having kept track of these stories in the past, we’re also losing success stories, right? Tell us about some of the examples that you’ve you’ve come across.

Wintersmith: Yeah, the podcast does travel to Austria and to Evanston, Illinois to look at successful examples. I think what’s probably most similar across all of the places that we’ve looked at is that where there are reparations programs, there had to be a collective inflection point where people looked at themselves or looked at the society that they were sitting in and said, “Hey, we need to do something differently” and then there also needed to be someone in political power to sense that there was an inflection point and then go along with the direction that society wanted them to go along in.

Rath: It’s intense, obviously, when it’s happening in a postwar context, like when you think about Austria and the de-nazification of Europe, but as you mentioned, there was a huge will after the war to take that on. How would a place though, like Evanston, Illinois, when America hasn’t had that kind of truth and reconciliation moment? How do you dig in?

Wintersmith: You hear in one of the episodes in particular that focuses only on Evanston, that Robin Simmons, who was an alderwoman for the city at the time that the reparations program got on the ground, was really motivated to have that conversation and did the work of community education and did the work of calling some other folks in to be ambassadors of the idea. You’ll hear from politically connected folks in that city who wanted to make it much more of an issue that folks contemplate as they make their political choices. You’ll also hear from community activists who were very passionate about sharing some of the forgotten history. Going back to what you and I said at the beginning of this conversation, that we’re learning as we explore and revisit things from the past. Sometimes it’s not top of mind for people, and then all it takes is for a knowledgeable person to bring some piece of history to folks’ attention. Then folks say, “Hey, I didn’t know that. Let’s do something about that.”

Rath: When people hear the word reparations, I think the tendency is to think about material compensation. Going back to that idea of 40 acres and a mule or more recently, I think people think of cash compensation, but reparations look a lot of different ways from that, right?

Wintersmith: They do. So in Evanston, which again, is the nation’s first local reparations program, they are handing out cash payments now, but it started several years ago as a restorative housing program and they did that to rectify discriminatory housing policies and practices that the city partook in. I think they chose a time period that was like 1919-1969, and so if you were a Black resident and you experienced having to move out or not being able to get a loan, or you have a house and it needs some updating, you were eligible for reparations in that way.

In Amherst, down the road from us, which just completed its reparations recommendation process last October, they have a $2 million endowment and their reparations assembly proposed spending that money on youth programs and affordable housing and grants to bolster businesses.

I just want to add that in the podcast, we also touch on different examples of ways that people and politicians are trying to rectify past wrongs, but they don’t necessarily call them reparations. So one example, if you think about Black people largely being excluded from the GI Bill and the benefits that that program offered, there is pending legislation to go back and give the families of those folks who were denied some sort of benefit to rectify that past wrong. So you’re right. teparations can look a lot of different ways.

Rath: Coming back to Boston, where do things stand right now in City Hall? How has the reparations conversation moved or not?

Wintersmith: Well, the city have taken the step of hiring researchers to deeply investigate Boston’s connections to the transatlantic slave trade. So not just what we were saying about it being part of the first colony to legalize, but what are the ways, even if folks in Boston weren’t directly exchanging people, and we know in some cases they were, but what are the ways that Boston was integral to this practice? So that’s a fact, the city of Boston has hired those researchers. That process is ongoing. Whether or not the conversation has stalled at all or is moving forward, that’s a matter of perspective. You will hear in the podcast some pretty pointed criticisms of the Reparations Task Force, because it has been slow going. Even though the city has taken the step that I mentioned a moment ago, when you look at the legislation that made the task force, the hiring of researchers should have happened a while ago and that’s caused some concern for folks who are watching the process and waiting expectantly for more public engagement and some conclusions about what the city is going to do.

Rath: Saraya, great work. Thank you so much for coming on to share it with us, and really looking forward to hearing the full series.

Wintersmith: Thank you.

“What is Owed?” premieres Feb. 15 with new episodes every Thursday and is available wherever you get your podcasts.