Asheville – The Buncombe County Commissioners recently declined a request from the Community Reparations Commission (CRC) for a one-year mission extension. They approved only two months of additional support. On December 12, Dr. Dwight Mullen, who chairs the CRC, came before Asheville City Council with the same request.

He began by saying he is a professor, but he was coming before council to speak as a neighbor who, like those on the commission, had lived through the har imposed by institutions and systems like healthcare and education. Three times, he contrasted what the CRC was doing with the Watts Uprising. According to the official story, back in 1965, in Los Angeles, a young African-American motorist failed a sobriety test, resisted arrest, and was struck with a baton. Rumors spread among onlookers that the police had kicked a pregnant lady, and this led to a piling-on that lasted six days and resulted in 34 deaths and over $40 million in property damage. Mullen described the local community as having “escaped Watts.”

Although the CRC refused to supply a formal list of reasons justifying an extended timeframe, Mullen said the group had “very specific reasons.” First, while local governments were quick to respond to requests for data, other bodies, like the State of North Carolina, have not yet delivered. The findings from the $174,375 Cease the Harm audit have not been assembled, either. Mullen said he had no clue what the consultants were going to find, so he could not guess how long an appropriate response would take, but he was pretty sure it would take more than the two extra months Buncombe County approved.

Mullen described the CRC as slow to warm up, but now people from all subcommittees have found their footing, and they’re talking to each other with a shared vocabulary. This was a pioneering effort that didn’t conform to a template. People from all of Asheville’s black legacy neighborhoods are at one table for the first time.

At first, discussions covered pain and loss, but now they’re exploring possibilities for gain and hope. He added that it was difficult to talk about gains only for the black community when improvements to education, healthcare, and mental health benefit everybody. He described the CRC’s work as “not race-specific, but led by race.”

Members of city council did not bluntly state any accusations of wrongdoing, but they were not impressed by the CRC’s request for an extension. Councilwoman Antanette Mosley asked if the Cease the Harm study was going to include recommendations, “should there be any findings of harm.” Mullen replied that he had specifically asked that it include best practices.

Mosley said that, as far as she knew, Asheville had the only reparations committee that was designing reparations programs based solely on community input. She asked at what point Mullen intended to consult subject-matter experts.

Mullen said he plans to bring in historians, social scientists, and others, but one of the reasons the CRC needed more time was that it was working through community engagement. Discussions also had to be conducted with the private sector for its role in enforcing harmful policies, even now, and conversations imputing blame can be difficult.

He then spoke of the harm, which he said the commission might not have time to address. He said groups typically look for malevolence and hostility, but a lot of the harm is silent, from neglect and ostracization. The commission represented people who did not want to live this way anymore.

Councilwoman Sheneika Smith asked why they had to keep holding meetings. She suggested the committee review the Cease the Harm report and then let community engagement take on a life of its own. CRC Vice Chair Dewana Little replied that one reason the committee is moving so slowly is that it is listening to community input and modifying its direction in response.

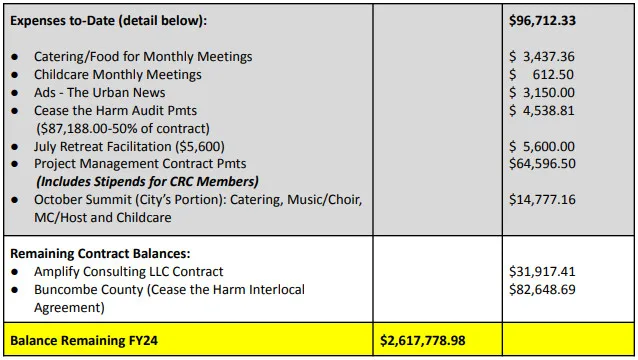

Councilwoman Kim Roney said that, as an educator, she knew what that spark of energy that brought the classroom together felt like. So, she appreciated the need to keep holding meetings, just like convening class throughout the year. While she supported the extended timeframe, she added that when the city dedicated the proceeds from the sale of what is now the White Labs property to reparations, she thought funds would be used to address social determinants of health instead of meeting costs.

Mullen replied that he saw the budgets Roney referenced for the first time when she saw them. “I had no idea,” he said. He added that it may look frivolous to eat and chat, but “those processes never occurred in the communities.”