After political pressure and repeated revisions, the College Board has reinstated some content, while steering clear of critical race theory and other ideas targeted by conservatives.

The latest version of the College Board’s A.P. African American studies framework may not fully please its critics — either the discipline’s scholars or politicians who have tried to legislate against it.

The Advanced Placement curriculum, released on Wednesday, leaves out critical race theory and structural racism, which academics say are key concepts. L.G.B.T.Q. issues continue to be mostly absent, except to mention that the civil rights leader Bayard Rustin was gay. And despite the course’s origins around the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, study of the movement is optional.

The curriculum does mention “systemic oppression” and “systemic marginalization,” ideas closely related to critical race theory and structural racism — terms that have been banned from classrooms in many states.

Those concepts have origins in legal theory, and refer to the idea that racism is embedded in the legal system, education system and other institutions.

The course framework also reinstates the term “intersectionality,” the study of how racism, sexism, classism and other forms of discrimination overlap and shape individuals’ experiences of the world. And the class now requires teaching about Black feminism and police violence.

The College Board did not respond on Wednesday to questions about why some topics are excluded. But Brandi Waters, the lead author of the course framework and program manager for A.P. African American studies, said in a statement, “This is the course I wish I had in high school. I hope every interested student has the opportunity to take it.”

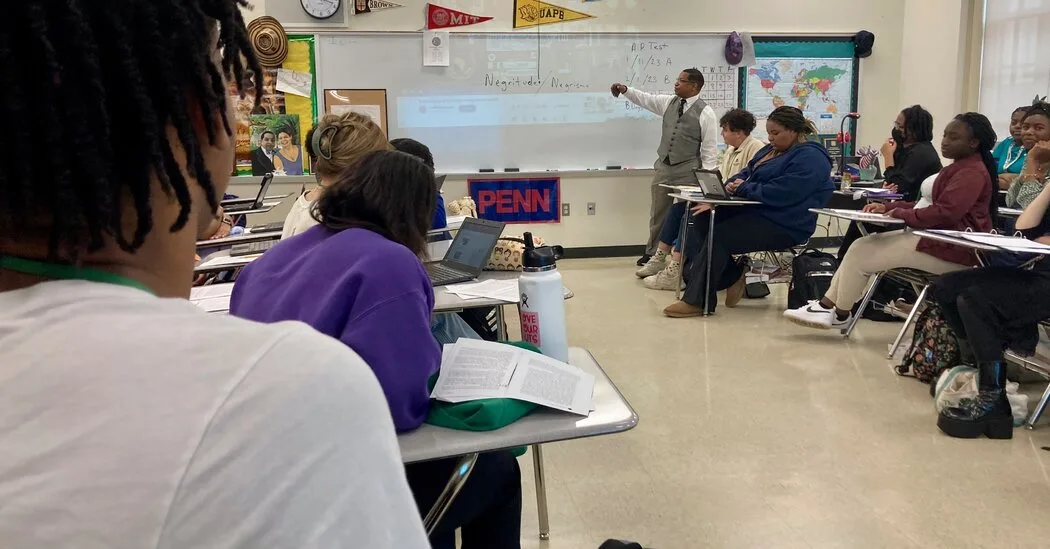

The course will launch for credit next fall, and is currently being taught as a pilot program in 700 schools across 40 states.

Since the College Board first officially released a curriculum in February, the class has caused no shortage of headaches for the organization. The course has been subjected to repeated revisions, tense political negotiations and scrutiny from scholars.

African American studies is an interdisciplinary field, melding history with the study of contemporary politics, culture and law. Many of its scholars embrace activism, an orientation that has drawn harsh rebukes from conservatives.

It did not help that the College Board initially concealed from scholars and the public the extent of its discussions with policymakers in Florida regarding the course’s content. That state’s governor, Ron DeSantis, a Republican presidential candidate, has signed multiple laws against what he sees as liberal orthodoxy in public schools.

In emails and meetings with College Board staff, Florida education officials repeatedly raised concerns about specific material in the class framework, such as intersectionality.

After those discussions, the Board removed some of the disputed content, which did not stop Governor DeSantis from announcing he would not permit the class to be offered in Florida.

Then, after intense pressure from leading Black studies scholars, the organization said it had made mistakes in its dealings with the state, and promised to revise the course yet again, and to work closely with academics.

The Florida Department of Education did not immediately respond Wednesday to a request for comment on the revisions.

In revising the curriculum, the College Board said it was guided by subject-matter experts and feedback from teachers and students. Still, the revision took place in a highly politicized environment. Dozens of Republican-led states have passed laws restricting instruction on critical race theory, structural racism and gender. The College Board did not respond to questions about whether it considered these laws in the revision process.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a leading Black studies scholar and originator of the concept of intersectionality, said some of the board’s revisions were welcome, though she said she would continue to protest the fact that “structural racism” and “Black queer studies” remained “sidelined.”

“What should worry us all at this point is the fact that an institution as powerful and well resourced as the College Board found itself in the crosshairs of a politically motivated censorship campaign,” she wrote in an email.

Matthew Guterl, a professor of Africana studies at Brown University, said the new curriculum framework was “modestly improved” relative to past versions. But he noted what he characterized as a lack of depth on topics of political importance over the last several decades, including L.G.B.T.Q. issues, mass incarceration, police violence and poverty.

“After the civil rights movement, the coverage gets spotty and the source material does, too,” he wrote in an email.

The College Board began to develop the class in 2020, hoping to capture young people’s interests in contemporary race issues following mass protests after the murder of George Floyd. The class was also intended to diversify the group of students who enroll in Advanced Placement, a longtime goal of the board.

Amid the rapid decline of the SAT, the Advanced Placement program has become the biggest revenue generator for the College Board, a nonprofit, and African American studies is one of several new courses it has developed in an attempt to draw new students to the program.

The course’s format also represents a shift.

There will be an exam in African American studies, but 10 percent of the final score will be determined by a research project on a topic students choose: In previous drafts of the course framework, the project accounted for 20 percent of the final score.

Traditionally, A.P. courses culminate in timed tests, graded 1 to 5, in which students have had to earn 3 or better to qualify for college credit, regardless of their class performance. But given deep disparities in how low-income, Black and Hispanic students perform on those tests, the Board is increasingly experimenting with classes that culminate in projects or presentations.

The new A.P. course contains many topics that are typically absent in the American high school curriculum, ranging from the achievements of ancient African civilizations to Black women’s resistance to sexual violence under slavery.

The final framework also adds more information on Black sports figures, including the N.F.L. quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who kneeled during the national anthem to protest police killings of Black Americans.