Biased Discretion of Criminal Legal Practitioners

A. Racial Bias Among Criminal Legal Professionals

While most white Americans no longer endorse overt forms of prejudice associated with the era of Jim Crow racism—such as beliefs about the biological inferiority of Black people and support for segregation and discrimination—a nontrivial proportion, including those in law enforcement, continue to express negative cultural stereotypes of Black people, including stereotypes of criminality. Implicit racial bias—unintentional and unconscious racial biases that affect decisions and behaviors—is pervasive among white Americans, and affects many people of color as well. These biases are held even by people who disavow overt prejudice.

Studies of criminal legal outcomes reveal biased decision making in the work of police officers, prosecutors, judges, correctional officers, parole boards, and other members of the courtroom work group. One factor driving these outcomes is the paucity of people of color in these professional roles. Increasing the representation of communities of color among criminal legal professionals is necessary, but insufficient, for ending injustice. As the Center for Policing Equity has noted, “Law enforcement policies, procedures, and culture…are shaped by White supremacy. Any [police] officer working in such a system risks finding themselves engaged in behavior that is racist in nature, even if they do not, personally, hold racist beliefs or are themselves, Black.”

Prosecutors

Prosecutors are more likely to seek imprisonment and to secure longer prison sentences for people of color than whites for similar crimes. Federal prosecutors, for example, have been twice as likely to charge African Americans with offenses that carry mandatory minimum sentences than whites with similar offenses and criminal histories. Although prosecutorial practices are often opaque at the local level, a growing commitment to transparency, particularly among reform-oriented prosecutors willing to share data with researchers, has provided a better understanding of disparities in many jurisdictions. Charging disparities for similar crimes in Massachusetts have increased the likelihood that Black and Latinx people are directed to Superior Court than whites, where the available sentences are longer than in District Court. Prosecutors in Ann Arbor, Michigan, brought more charges and secured more convictions per case for people of color than whites, contributing to their acquiring a “habitual offender” status and facing harsher future treatment in the courts. More broadly, state prosecutors have been more likely to charge Black than similarly situated white defendants under habitual offender laws. Prosecutors in Chicago, Jacksonville, Milwaukee, and Tampa have also been less likely to divert Black and Latinx individuals from felony charges than their white counterparts, in a pattern that offense severity, criminal history, and age do not explain. Black people in Denver have been less likely to benefit from deferred prosecution, and controlling for factors including case severity and age did not eliminate the difference. Researchers have also documented disparities in plea deals in jurisdictions such as Wisconsin. By allowing this scrutiny of their work, many of these prosecutorial offices are making it possible to craft appropriate reforms to tackle sources of disparity.

Prosecutorial discretion also tends to disadvantage Black individuals both in early stages of criminal legal processing—jury selection—and in later stages involving parole consideration. As Wake Forest Law Professor Ronald Wright has observed about North Carolina, prosecutors’ peremptory challenges, in which they reject prospective jurors without explanation, are “a vehicle for veiled racial bias that results in juries less sympathetic to defendants of color.” California prosecutors have also been more likely to oppose parole release for Black versus white and Latinx individuals, after controlling for differences in factors such as age, commitment offense, criminal history, and educational attainment. More broadly, line prosecutors often espouse a racially-colorblind approach to their work, which is often contradicted by the results of their work and “perpetuates inaction in the face of racial disparities” by failing to mitigate upstream disparities. In addition, some view their punitiveness as beneficial to Black defendants and their communities.

Further, prosecutors help to write the laws that they enforce. Many district attorney associations lobby, litigate, and engage in public advocacy against reforms that might lessen racial disparities, and oppose the work of reform-oriented prosecutors. “American prosecutors are active lobbyists who routinely support making the criminal law harsher,” writes Carissa Byrne Hessick, the Ransdell Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina. Her team’s 50-state study found that between 2015 and 2018, state and local prosecutors were involved in more than one-quarter of all criminal-justice-related bills and were nearly twice as likely to lobby in favor of a law that increased criminal penalties or added new crimes than for bills that might narrow the scope or punitiveness of criminal law. In 2019, 95% of elected prosecutors were white, with 73% being white men.

Judges

In 2016, 80% of state trial judges were white, in contrast to 30% of the defendants whose cases they oversaw. Moreover, 18 states have no supreme court justices of color. Studies that account for differences in crime severity and criminal history show that judges have been more likely to sentence people of color than whites to prison and jail and to give them longer sentences. In federal court, the sentencing disparities between noncitizens and citizens are even larger than those across race. In research from the Northeast and news coverage of Florida, judges expressed some willingness to mitigate their own biases, but little will to use their discretion to address disparities caused by other criminal legal professionals or by laws with a disparate impact.

Correctional Officers, Parole Boards, Probation and Parole Officers

Biased reactions by correctional officers to the behaviors of incarcerated individuals leads to racial and ethnic disparities in prison discipline, including in disciplinary write-ups that can lead to placement in solitary confinement and later disadvantage people of color in parole hearings. There is also evidence of racial bias in discretionary parole decisions after controlling for factors such as rehabilitative efforts, crime of conviction, and disciplinary history. Parole boards rely on their own subjective assessments of candidates’ remorse and insight, a decision-making process prone to cultural and racial bias. In fact, in light of parole boards’ unwillingness to release qualified individuals, legal experts such as the American Law Institute call for abolishing these entities and relying on judicial authority for release decisions. Probation and parole supervision officers are also more likely to conclude that people of color, compared to whites, have violated the terms of their community supervision, triggering their imprisonment.

Juries and Defense Attorneys

People of color are underrepresented in juries across the country, which studies show produces bias in outcomes. Racially diverse juries deliberate longer and more thoroughly than all-white juries, and studies of capital trials have found that all-white juries are more likely than racially diverse juries to sentence individuals to death. A study in Florida found that all-white jury pools convicted Black individuals 16% more often than whites. Studies of mock jurors have even shown that people also exhibited skin-color bias in how they evaluated evidence: they were more likely to view ambiguous evidence as indication of guilt for darker skinned suspects than for those who were lighter skinned. Defense attorneys may also exhibit racial bias in how they triage their heavy caseloads and struggle to gain some disadvantaged clients’ trust.

B. Addressing Racial Bias Among Criminal Legal Professionals

This section presents reforms to mitigate racial bias in prosecutorial decisions and across the criminal legal system, including jury deliberations and parole hearings.

Reducing Racial Disparities in Prosecutorial Decisions

Three states have addressed the role of peremptory challenges in limiting jury diversity. First, Washington State’s Supreme Court adopted a rule in 2018 expanding the prohibition of race-based peremptory challenges to include “implicit, institutional, and unconscious” bias. Two years later, California’s legislature shifted the burden of proof for peremptory challenges: the state now requires attorneys who remove a prospective juror to prove that the cause was not race or other prohibited factors. And finally, following a state Supreme Court ruling acknowledging their role in discriminatory jury selection, Arizona became the first state to eliminate peremptory challenges in 2022.

Prosecutors themselves have begun reforming charging decisions in some jurisdictions. To address the disproportionate prosecution of African Americans in San Francisco, prosecutors in 2019 tested out the process of “race-obscured charging” by concealing race and related information. In race-obscured charging, prosecutors have access only to the reason a person was stopped, evidence that the person committed a crime, and witness accounts. They access all other information after making their initial decision. The Yolo County District Attorney followed suit in 2021 and led the California legislature to mandate this reform statewide by 2025. But because the decision of whether to bring charges may not be a key site of bias within a particular jurisdiction, prosecutors’ offices should prioritize data collection and transparency so that reforms can be tailored to local drivers of disparities.

For over a decade, the Vera Institute of Justice has worked with prosecutors around the country to tackle racial disparities. In Milwaukee, Vera found that prior to 2006, prosecutors filed drug paraphernalia charges against a greater proportion of Black than white defendants. The prosecutor’s office was able to eliminate these disparities by reviewing data on outcomes, encouraging diversion to treatment or dismissal, and requiring attorneys to consult with supervisors prior to filing such charges.

More recently, Vera’s Motion for Justice initiative has recommended that prosecutors presumptively exclude all consideration of criminal histories from charging, diversion, and sentencing decisions. Prosecutors in Los Angeles and Alameda counties revised their offices’ charging practices, amidst strong resistance from the Los Angeles prosecutors’ union and Alameda County staff prosecutors, so as to not trigger California’s three-strikes law. Researchers have also found that in Florida, prosecutors’ willingness to offer plea deals below sentencing guidelines for those with prior convictions contributed to Black decarceration outpacing white decarceration.

Reform-oriented prosecutors are also taking on extreme sentencing more broadly. In 2021, over 50 elected prosecutors joined in a statement issued by the organization Fair and Just Prosecution, calling for office policies “whereby no prosecutor is permitted to seek a lengthy sentence above a certain number of years (for example 15 or 20 years) absent permission from a supervisor or the elected prosecutor.” To curb excessive penalties resulting from plea deals, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner has instructed his office to generally make plea offers below the bottom end of the state’s sentencing guidelines.

Vera also advises that prosecutors “advocate against state statutes that call for more punishment based on prior criminal contact, such as three strikes sentencing and habitual offender “enhancements,” or that indirectly exacerbate prior criminal contact issues by targeting Black and Latinx people, such as drug-free zone laws.” In recent years, some reform-oriented prosecutors have left their state district attorney associations due to their anti-reform positions. In addition, many have partnered to advance reform through organizations such as For the People and Prosecutors Alliance of California. For example, over 60 reform-minded elected prosecutors and law enforcement leaders working with Fair and Just Prosecution have called for second look legislation, and several have launched sentence review units.

Backlash Against Prosecutorial Reforms and Independence

While many cities are electing, and reelecting, reform-oriented prosecutors, these officials face substantial backlash. A well-funded campaign led to San Francisco voters recalling District Attorney Chesa Boudin in 2022 and a campaign is underway to remove Alameda, CA DA Pamela Price. In Los Angeles in 2022, DA George Gascón survived his second recall attempt in as many years with both efforts failing to gather enough signatures to make it on the ballot. In Philadelphia, the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania rejected attempts to impeach District Attorney Larry Krasner, finding no legal basis for his removal.

Some Republican governors and lawmakers are also taking aim at prosecutors elected in their Democratic-majority cities. In 2023, Georgia Governor Brian Kemp signed a bill to create a commission with the power to oversee, discipline, and remove prosecutors elected in the state. Sherry Boston, DeKalb County DA, said this legislation “is not just an assault on prosecutors. It is an assault on our democracy.” In Florida, Governor and 2024 presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis has removed two prosecutors: Andrew Warren was removed in Tampa due to his pledge not to prosecute people who seek or provide abortion or gender transition treatments and Monique Worrell was removed in Orlando for her office’s criminal charging decisions. Lawmakers across the country are similarly attacking prosecutorial independence with efforts disproportionately targeting black female prosecutors.

Addressing Bias Among Jurors

Several jurisdictions have worked to increase the diversity of jury pools and to mitigate bias among jurors. Federal and New York state courts are transparent about how the racial and ethnic composition of their jury pools compares to their broader communities—a critical step for achieving diverse jury pools. The Iowa Supreme Court has ruled that courts must use more rigorous tests to determine whether the racial composition of juries meet the constitutional right to an impartial jury.

Mock jury studies have shown that increasing the salience of race and making jurors more conscious of their biases reduces biased decision making. The practices of U.S. District Court Judge Mark W. Bennett when he was on the bench presents one model. He spent 25 minutes discussing implicit bias with the potential jurors in his court. He showed video clips that demonstrate bias in hidden camera situations, gave specific instructions on avoiding bias, and asked jurors to sign a pledge to address their biases. The Iowa Supreme Court now also strongly urges judges to instruct jurors to not be swayed by racial bias in reaching a verdict.

Empowering Judges to Correct Injustices

In some jurisdictions, judges can now use their discretion to correct racial and ethnic injustices in sentencing. Both California and Utah now also allow people to seek resentencing if they can demonstrate that bias affected them. California’s Racial Justice Act allows people to ask the courts to vacate a conviction or sentence by proving with a preponderance of the evidence that an attorney, police officer, juror, judge, or expert witness exhibited bias or used discriminatory language about their race, ethnicity, or national origin. This includes showing evidence of racial disparities in charges, convictions, or sentences. Likewise the Utah Sentencing Commission approved revisions to that state’s sentencing guidelines allowing defendants to argue that racial, ethnic, or other biases—whether conscious or unconscious—can be considered as a mitigating factor.

Developing Objective Criteria for Parole Release Decisions

To reduce subjective parole release determinations—which are often politicized and laden with bias—states are increasing evidentiary standards for parole boards, creating presumptive parole policies, and developing objective criteria. In 2018, Michigan passed the Objective Parole law, which requires the state’s parole board to adhere to a set of objective, evidence-based guidelines. Idaho, Massachusetts, Missouri, and the federal parole system also use a “clear and convincing evidence standard,” which raises the necessary burden of proof for denying parole.

New York’s legislature, courts, and governor have demanded that the state’s parole board give greater weight to how candidates have changed, to reduce their focus on the underlying offense, and to record their decision-making process. In 2021, Maryland joined most other states (with California being among the notable exceptions) in ending gubernatorial reviews of parole decisions for people serving eligible life sentences.

Finally, New York and North Carolina require their parole boards to publish race, age, and other demographic data related to parole outcomes—a critical component of uprooting disparities. Alabama and Alaska also make this information available.

Ensuring That Criminal Legal Practitioners Are Diverse and Include Impacted Populations

“Agencies enjoying good reputations in the law enforcement profession and in their communities also benefit from larger, more diverse applicant pools,” reports Governing, suggesting a virtuous cycle between representation and justice. Increasing the representation of people of color among law enforcement and courtroom professionals requires reforms including improving K-12 civics education, creating mentorship programs for attorneys of color, and increasing outreach efforts to attorneys from diverse backgrounds to pursue judicial careers. The Supreme Court’s July 2023 ruling striking down affirmative action in college admissions highlights the urgency in safeguarding these equitable hiring practices and ensuring diversity and representation among criminal legal professionals.

Formerly incarcerated individuals are also beginning to enter elected office and criminal legal agencies. In 2020, Washington State elected its first formerly incarcerated individual, Tarra Simmons, to the state legislature and the New York State Assembly similarly made history in 2022 with the election of Eddie Gibbs. Joel Castón became the first person to be elected to office in Washington, DC, while incarcerated: he won a seat on his Advisory Neighborhood Commission in 2021. Rhode Island’s state legislature currently has two formerly incarcerated representatives: Leonela Felix and Cherie Cruz. In addition, Minnesota recently mandated the inclusion of a directly impacted individual on the Sentencing Guidelines Commission and, in 2019, the Pennsylvania Lieutenant Governor’s office hired two formerly incarcerated individuals as Commutations Specialists for the Board of Pardons.

Tarra Simmons is a member of the state House of Representatives in Washington’s 23rd Legislative District. Photo credit: Washington State Legislative Support Services.

Tarra Simmons is a member of the state House of Representatives in Washington’s 23rd Legislative District. Photo credit: Washington State Legislative Support Services.

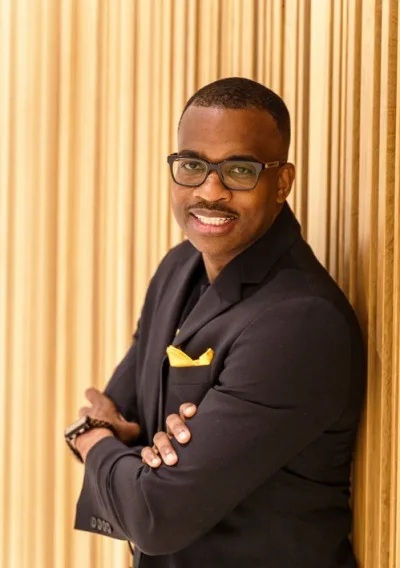

Eddie Gibbs represents the 68th district in the New York State Assembly. Photo courtesy of the office of Assemblymember Gibbs.

Cherie Cruz (left) and Leonela Felix (right) are state representatives in the Rhode Island House of Representatives for the 58th and 61st districts, respectively. Photo courtesy of Leonela Felix.

Joel Castón served as an Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner in Washington DC while incarcerated at the DC Jail. Photo courtesy of Joel Castón.