As part of our ongoing series on Re-Imagining Public Safety, we interviewed Ramsey County’s chief prosecutor John Choi, the first Korean American chief prosecutor in the U.S. He was elected to that office in 2011 and has since led progressive justice reform. He first worked with community partners to transform responses to domestic violence, sex trafficking, and sexual assaults in Minnesota. He has worked to reform state drug laws, invest in community-based solutions, support restorative justice practices for youth, and reunite families when it is in the best interest of foster children. He established a Veterans Court in 2013 to address underlying problems of people who might be struggling as a result of their military service. His office worked with county law enforcement to reduce reliance on equipment-related traffic stops — turn signal lights and expired tabs — and supported a program to send letters to those vehicle owners instead to offer financial assistance for repairs and registration.

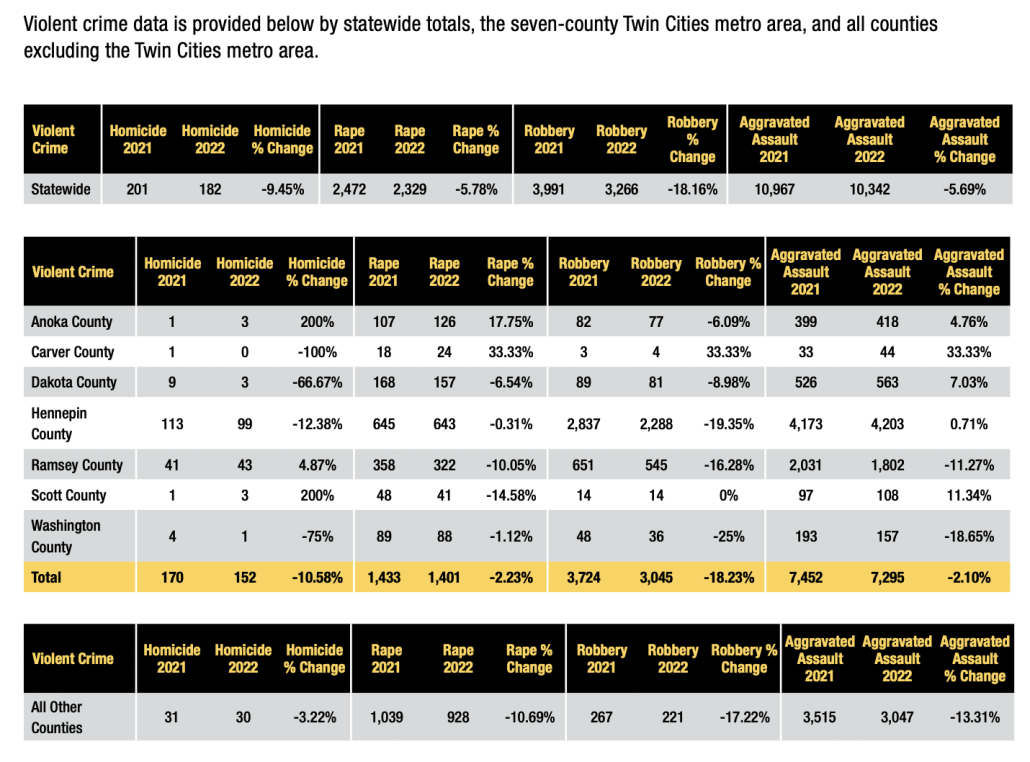

Critics claim these practices have made Saint Paul and the neighboring cities less safe. Data from the Minnesota Uniform Crime Report indicates robbery, rape, and aggravated assault in Ramsey County went down from 2021 to 2022. Homicides went up in that time from 41 to 43, compared to 113 homicides in Hennepin County in 2021 and 99 in 2022.

Choi says he inherited a justice system when he stepped into office in 2011 that had begun hundreds of years earlier. The system, he says, was not originally designed with best practices about how to reduce crime, provide justice for the community, and offer healing for victims. A growing number of people are raising questions about how effective it is. [These questions were raised more than 100 years ago, when psychology became more prevalent in western society; many African and indigenous populations have always deferred to restorative justice.]

Criticism tends to be loudest from those inspired by fear about crime rates who claim that not enough criminals are being arrested and imprisoned after the fact. There might be more success in reducing crime, he indicates, if we did more to understand why people commit crime and divert them from that path — and if trust was improved with policing so that those engaged in criminal behavior can be apprehended.

He concurs with other progressive-minded prosecutors that more justice resources could be used to rehabilitate rather than simply incarcerate. Many people have been trained to believe that the short-term solution of locking people away is effective in preventing crime, and offering healing. In many cases, however, that is a short-sighted response.

The following are Choi’s direct perspectives from our conversation.

What People Don’t Understand About the Justice System

Ramsey County attorney John Choi during our Zoom discussion

What People Don’t Understand About the Justice System

There’s this belief that we have jury trials all over this country every day. We do, but we don’t have enough courtrooms. We don’t have enough judges to have a trial for every case. We have trials every week — there’s probably three or four trials that happen here in Ramsey County involving felony cases — but for the most part, everything else is done through a process of negotiations and plea bargaining. It efficiently processes situations and tries to give some restitution to the victim. It tries to represent generally what the state’s interest is. But it’s usually a very simple solution compared to what we see on TV.

We have a system that tends to want to have a consequence for a consequence, an eye for an eye. Our system is rooted more in punishment than it is around rehabilitation, reconciliation, redemption — values that are dear to this community. People go to places of worship where we’ve learned of mercy and grace, but it doesn’t thrive in the criminal legal system.

If we ask people “What outcomes do you want?” and then ask “Does this current legal system actually get us there?” I think we would not be hitting the mark on rehabilitation. We aren’t getting [harmful] behavior to stop by addressing the root causes of why people find themselves in certain situations.

Our investments shouldn’t just be in reacting to bad things that happen, but trying to prevent them through better socio-economic conditions, education systems, economic opportunities. Instead, we have a system that just processes these situations like an assembly line. This assembly line leads to a black mark on someone’s forehead.

One of the biggest challenges is in understanding that the system is set up to address the fears of certain communities but not others. There are communities dealing with the impact of crime that happens right in front of them. [Those are the people who would like to see real change happen so that when people are back in their community, those behaviors have stopped.]

We produce a lot of racial disparity. There are enormous consequences on people in the justice system who are struggling with mental health issues or drug addiction issues, then end up with a lifetime of having a felony conviction on their record, which leads to more unequal access to housing or employment.

If more people paid attention, we’d probably be thinking about more alternatives like restorative justice, which are based upon African and Native American resolutions. Restorative justice is centered around trying to address the harm that somebody has caused and allowing victims to express how that harm has affected them.

The Pushback in Justice Reform

In 2019, as a part of my engagement with the Vera Institute of Justice and the John Jay Institute for Innovation in Prosecution, I was at a conference in New York. We were talking about the prosecutor’s role in helping shape a better version of policing and justice across this country, and the power that we hold to change systems that are doing harm to communities.

One conversation was related to how we handle traffic stops. Police pull somebody over if they see a light bulb out on a car, or a tab that’s expired, as a pretext to pull somebody over to do a further investigation — it’s late at night and what are you doing in this neighborhood? The idea was that it was good policing, proactive. And we would find guns or drugs. But that’s not true at all.

As a prosecutor, do I want to incentivize that police practice when it undermines the trust that is necessary between police and community?

When I brought that concept back to Minnesota, it was met with a lot of resistance. Nobody wanted to touch it — then George Floyd was killed [after being suspected of using a counterfeit $20 bill]. After that, there was an opportunity to have deeper conversations with police leaders. I made it clear that I was going to assert my role as a prosecutor — since I control the front door of the criminal justice system, you can’t bring a case to me if it was a product of a non-public-safety traffic stop.

Tyrone Terrell, president of the African American Leadership Council, came up to the podium without prompting. He grabbed the microphone and said, “My community has suffered the most violence. My community is at the heart of what you’re talking about in terms of being victimized. I can also tell you that my community gets impacted by these non-public-safety traffic stops. Driving while Black is real. Can’t you give this a chance? Can’t you just let us tell you what our experiences are?”

President Biden picked up on this part-way. He talked about how parents of Black and brown kids have to have this talk with their children who are about to drive about the realities they might face when they get pulled over and how they might need to interact with police. President Biden said that is sad and not right — but I think he stopped short. I think we need to take that one step further to make it right. We shouldn’t be asking Black and brown parents to continue to have that conversation and live with that reality. Our systems should change.

Of course, this is long-term work. You can’t change this massive thing that we call the legal system overnight. It’s like trying to make a cruise ship do a 90-degree turn — it will turn over. So you have to bring your community along with you and you have to mind your pace. Where is the majority of the public?

It is our responsibility to try to engage. This belongs to all of us — everyone needs to start becoming more involved and having a sense of ownership of what happens in the justice system.

We will never get there if we’re stuck on the fear-based approaches that we’ve taken. We’ll never get there unless we ground ourselves in the data, hard conversations, and allowing for innovation. The definition of insanity is to do the same thing over and over again and expect different outcomes.

How Media Perpetuates Fear

The media tells the story of how somebody commits a crime who was on probation, but we don’t hear about when someone was given probation and they successfully turned their lives around. That happens more often than not. If you give someone a shot at diversion, something good can happen. That’s never in the mindset of most people because we don’t hear those stories. What sells in the media is to stoke fear.

Being the victim of criminal behavior is emotional and raw. The impact of violent crime on an individual is huge. That is what makes it so hard. Some of the toughest conversations I’ve had as county attorney is when somebody has been killed and the victim’s family wants life in prison — this person took my son’s life. But we also represent the broader community interests, and we have to be followers of the law.

If I can’t prove this person committed first-degree murder [premeditated or in the act of another violent crime like domestic abuse], it would be wrong to convict the person of that — the conviction is more likely for manslaughter [negligence that leads to death and can be sentenced to imprisonment for not more than ten years, or payment of a fine up to $20,000].

We’ve been raised to believe that it’s an eye for an eye — the justice we see on TV — and oftentimes to tell somebody they can’t get that version of justice is hard. Often the impacted families are African American, Black, and brown communities. They feel they are not getting justice from a system that [rarely delivers it in daily life]. That’s a hard conversation.

I think you see that happening in Hennepin County, where the media is picking up on this tension point between victims’ families and what the prosecutor’s office is doing. But the job of that office is not to do exactly what the victims want — we must do what is permissible under the law as well as be fair & just.

I think Hennepin County attorney Mary Moriarty [who took office January 2023] is sometimes being treated unfairly by the media. I know there were many instances where her predecessor [in office 2007 to 2023] did not seek adult certification when people were killed, and I’m sure there was a victim’s family that was upset about it, but that was never really talked about. Today there’s a narrative [that Moriarty is soft on crime].

Every day the news releases from the Hennepin County attorney’s office indicate that murderers and rapists are being convicted, sentenced for 30 years or some lengthy amount, and none of that is reported. What sells is when a victim’s family doesn’t get what they wanted.

It would be nice to see better leadership about how people cover crime.

How Can We Rehabilitate the System?

If you go to prison, there’s not much rehabilitation that’s happening there. It’s not designed for that.

I’ve been very involved in trying to combat gender-based violence. I believe that one of the biggest parts of the solution is the conversation about how we raise boys into men, and what people are expecting of boys and how that’s modeled. That conversation doesn’t happen enough. We also need to be good at separating out a serial rapist compared to a young person [who should not be branded as a sex offender].

I want to make it clear that prison and incapacitation is a legitimate part of our process. But it should be reserved for the most serious, violent situations.

In Minnesota, we do that pretty well. We are a low incarceration state, with high probation periods. But we warehouse people into these large prison institutions and the environment is not good. We could have smaller buildings, with different types of design and programming, to separate out [different levels of behavior].

This notion that prison makes us safer is simply not true. I think it actually has bigger negative impacts in the long term. In Ramsey County, we reduced our reliance on prison from 2012 to 2022, by well over 60 percent, and I don’t think we were any less safe than any other place in this country. Ramsey County has consistently been able to solve homicides — at a rate of above 90 percent — because there’s trust with the system and in communities, which is a big part of criminal justice.

Because so many believe the legal system has harmed, people don’t want to help that system. They believe there are other ways to exact justice. That’s when things start to fall apart. It is a bad thing when there is a deterioration of trust, especially on the front lines between police and community. Without community trust and engagement, we’re not going to be able to solve these crimes.

An important piece of criminal justice reform has to be about what doesn’t even get to the attention of the justice system. When we started work in 2011 around sex trafficking, we knew from talking to people who are helping runaway kids that there was a lot of sexual exploitation and trafficking of vulnerable people. Often, kids were the ones who were being arrested. But through the Safe Harbor approach, they are treating those kids as victims instead of violators of the law. We’ve created a system of services and supports.

The long journey is domestic violence. Back in 1990, the charging rate was about 30 percent. Police and prosecutors were thinking this was more of a private issue. If the victim didn’t want to participate, it closed the investigation. But a number of advocates changed that. We now have shelters and programs for victims. We still have improvements to make, because there is a lot of racial disparity in terms of who is convicted, and we still need more culturally appropriate programming.

How to Connect With and Divert Youth

It’s important that we do everything that we can to understand that kids are kids. It gets really hard when you have kids involved in violent crime. I do think that there is a place where you need to seek a longer sentence. But we have to be mindful of what we’re trying to do with each individual case.

There might be a murder, but there might be things about that young person who committed the murder and the circumstances of how it played out that need to be taken into account.

We also may want to set a process in motion so we can get more information about the youth and have more time to think about the appropriate resolution. After we get that, we have conversations with the defense and the judge. Ultimately, the judge likely will have to make that decision, but at least they will have all of that information.

Whether to certify a youth as an adult for a violent crime is a really tough place to be. At the end of the day, we’re just trying to make the right decision. We do have to understand and consider into our decision-making that this person is a kid. Brain development hasn’t occurred — that’s real. We’ve been talking about that for decades in terms of the science. It’s not just about giving it lip service; you really have to recognize that it is true.

Many serious youth cases end up with the system designating the young person as an ‘extended jurisdiction juvenile’ until age 21, which means they are often ordered to the state’s correctional facility for youth in Red Wing to complete rehabilitative programming. Many times the kids do well there. It typically takes somewhere between nine and 12 months for them to complete the programming, and then they receive intensive supervision in community until they turn 21.

A common refrain that you hear from corrections officers and judges is that in Minnesota we have difficulty finding appropriate placements to address underlying issues, whether it’s mental health or chemical addiction. Places are full, or don’t have the capacity to deal with that behavior, or they simply don’t want to work with that kid because he was there before.

In Ramsey County, we were able to get from the legislature in 2023 an appropriation of $5 million to build intensive therapeutic treatment homes to house and treat that population of youth. Another $5 million will be used for reentry services and supports, which is critical. I think the biggest challenge tends to be the environments in which some of these kids are living. We have to recognize that it’s hard to maintain rehabilitation or make the right decisions when the environment is challenging, whether that’s friendship networks or things happening within the home. Investments in reentry are critical.

We always tend to spend our money on the back end, responding to the most serious harm that happens. We need to be thinking more about preventing all of this and helping families and young kids with the services and support that they need.

Understanding Trauma as a Trigger to Behavior

The Veterans Restorative Justice Act is groundbreaking legislation that puts into place a method of recognizing trauma in Minnesota. Veterans can even avoid a conviction. The legislation is being looked at as a model to replicate for veterans throughout the country.

This is a foot in the door to better understand trauma and how we think about it when resolving a case. We’re becoming more evolved in our recognition of the fact that hurt people hurt people. We should be developing more prevention strategies around helping individuals who have experienced trauma.

One person in Shakopee women’s prison was [a victim of domestic violence who was convicted of killing her perpetrator]. She is serving a long sentence for that murder — close to 20 years. She is also attending law school while she is incarcerated and she submitted an application for commutation. It was probably going to be approved by the state attorney general’s office, but the victim’s family showed up for the hearing and gave heart-wrenching testimony about their loss.

Our justice system isn’t designed to help families like that. We had the trial, conviction, the sentence. The victims’ families go on to live their lives and then, years later, all of that trauma comes right back.

In the end, she didn’t get her commutation. On paper, she was probably a perfect candidate for it. It is an example of how sometimes values clash around redemption and the needs of survivors.