Alvin Hathaway was in awe as he slowly walked around the white-walled room surrounded by floor-to-ceiling windows, welcoming natural light from almost every direction.

Sporting a white construction hat and neon vest, the Baltimore native gushed over the progress made so far in transforming P.S. 103, the former school of Justice Thurgood Marshall in West Baltimore.

“I think this space is going to be absolutely phenomenal, because this is the space where we are going to be historically accurate as it relates to the restoration of an 1877 classroom,” Hathaway said of one of his favorite rooms in the formerly segregated school building.

The transformation of the school building into the Justice Thurgood Marshall Amenity Center is expected to be completed in late December, Hathaway said. The $14 million restoration joins several projects in Old West Baltimore, a national historic district, aiming to preserve the history, accomplishments and stomping grounds of significant people.

Old West Baltimore consists of a group of neighborhoods known today as Madison Park, Upton, Druid Heights, Harlem Park and Sandtown-Winchester, according to the National Register of Historic Places.

The historic district was once a bustling community of influential African Americans and has several significant ties to the Civil Rights Movement and Baltimore history. Harry S. Cummings, Baltimore’s first Black city council member, lived in the 1300 block of Pennsylvania Avenue.

Newcomers to Old West Baltimore might not know that it has seen better days. One could point to the riots of 1968 after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., gradual disinvestment, and the loss of population and businesses as reasons for its decline, but crippling racially discriminatory laws, drugs and mass incarcerations also played a role.

Through partnerships, Hathaway wants to fill the Justice Thurgood Marshall Amenity Center with learning opportunities for residents and visitors. The Judge Alexander Williams Jr. Center for Education, Justice and Ethics, part of the University of Maryland, College Park, will be a tenant. There are also plans for a “Project Takeoff” program to teach about aviation with flight simulators, as well as hospitality and airport management. And Hathaway envisions a “Stem City” in the center for introductions to artificial intelligence and the virtual reality.

“I think when people see historic properties come back to life, it kind of says that the old can become new and it sends a signal to people that their community is worthy of investment,” said Hathaway, a lifelong member and retired minister of Union Baptist Church in Upton.

Hathaway’s nonprofit, Beloved Community Service Corporation, acquired several properties for renovations, including the former office of Juanita Jackson Mitchell, the first Black woman to practice law in Maryland, and it will serve as a legal and social services hub in Upton. The corporation also purchased the Druid Hill Avenue homes of Juanita and Clarence Mitchell and John H. Murphy Sr., the founder of the AFRO American Newspapers.

Less than half a mile away from P.S. 103, AFRO Charities, the nonprofit that manages the newspapers’ archives, is renovating the Upton Mansion to house several decades’ worth of photos, letters and rare audio recordings. The mansion will also serve as headquarters for the nonprofit and the AFRO, one of the nation’s oldest Black newspapers. Savannah Wood, executive director for AFRO Charities, said there is $1.5 million left to raise of the project’s $13.3 million budget and that backers hope to break ground in spring 2024.

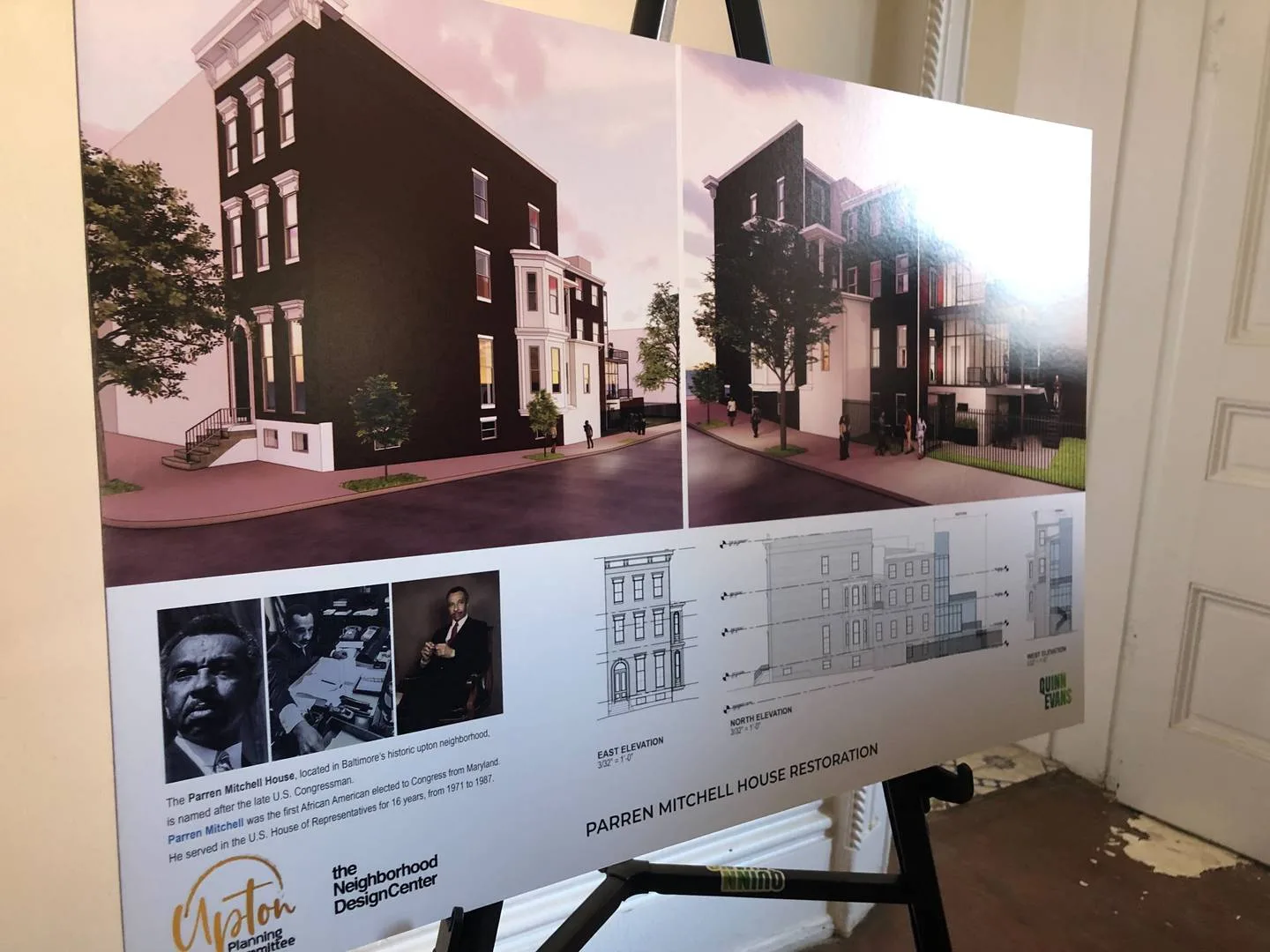

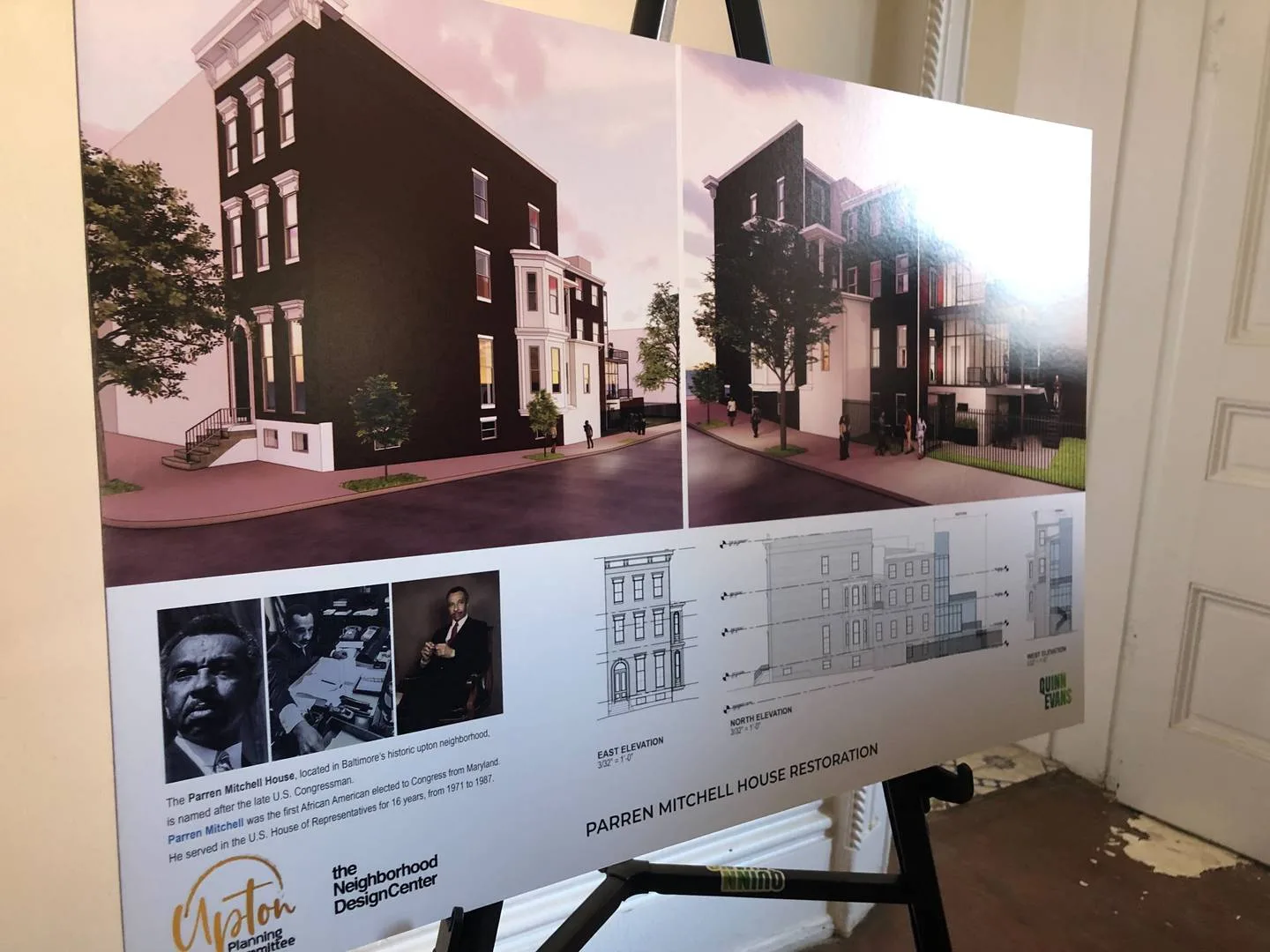

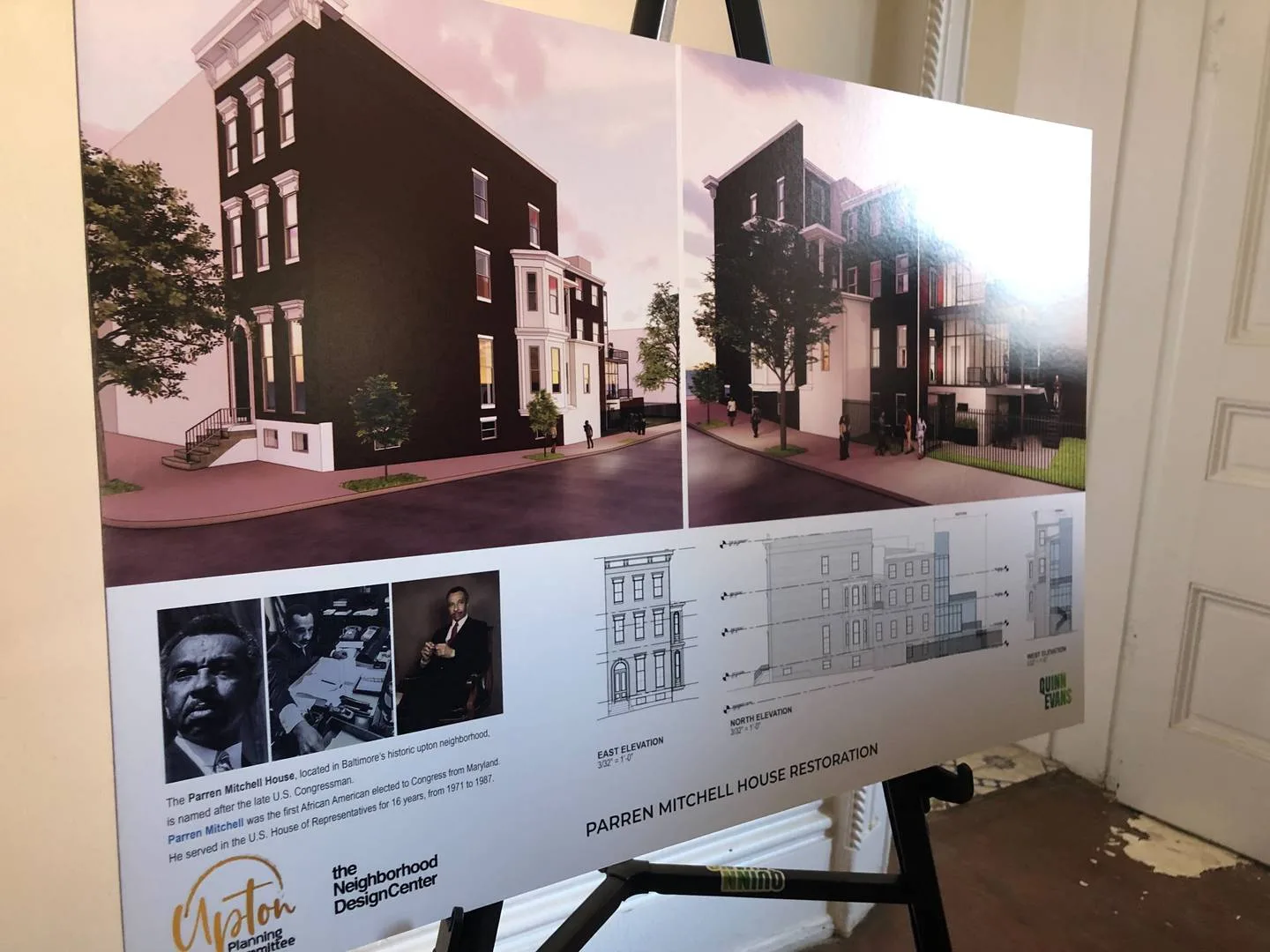

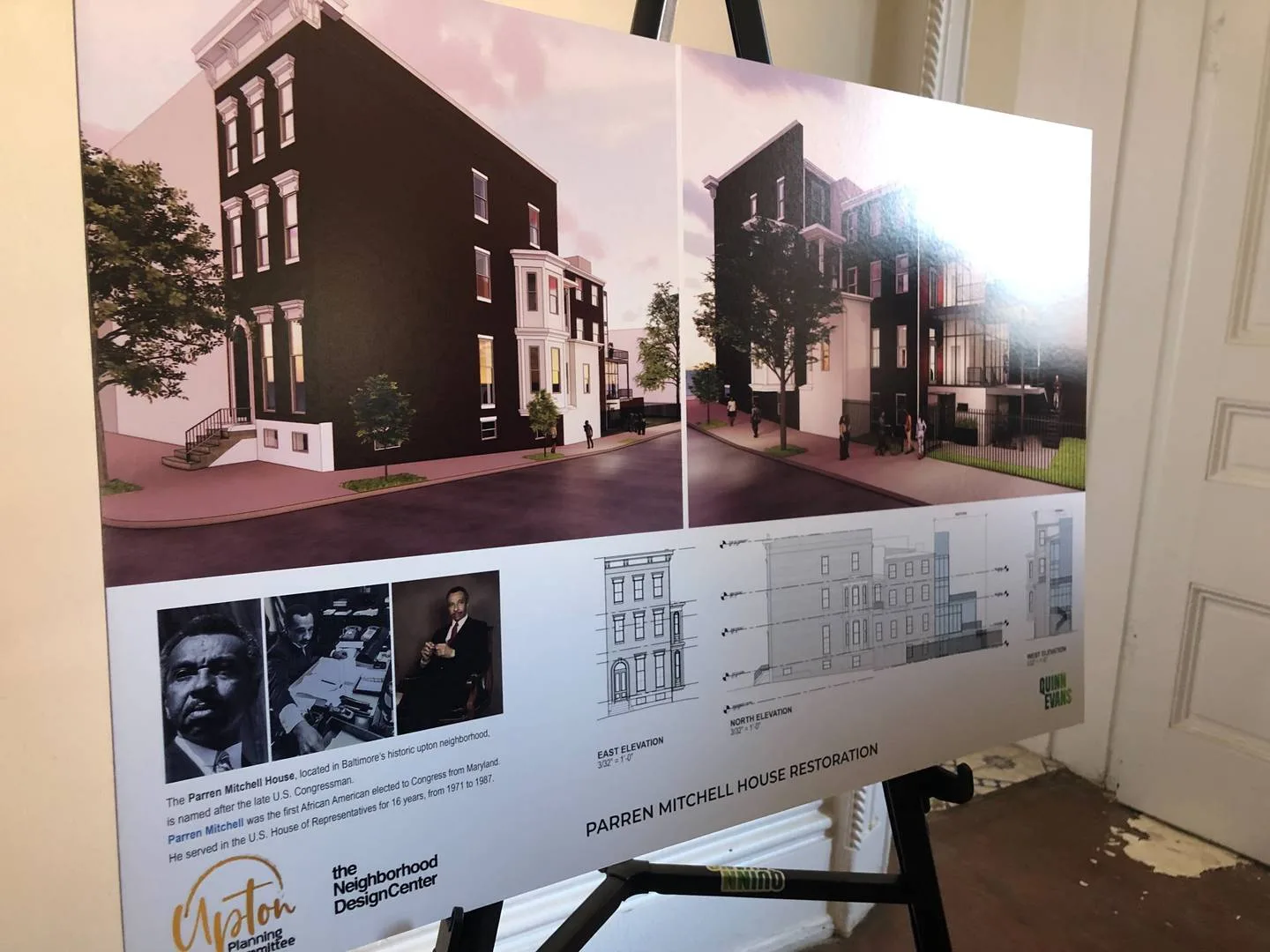

Earlier this month, the Upton Planning Committee announced plans to renovate the home of the late Congressman Parren Mitchell, the first African-American Marylander elected to Congress. Mitchell, who died in 2007, served for 16 years as a representative for the 7th Congressional district. He was one of the founders of the Congressional Black Caucus and prioritized civil rights and affirmative action throughout his career.

Five years ago, a friend of Mitchell who purchased the home gifted it to the committee and wanted to ensure that much of the building’s original details were not remodeled.

The state committed $1.5 million toward renovating the home, which is expected to cost at least $2.2 million; it will be called the West Baltimore Civic and Entrepreneurship Center. In partnership with Neighborhood Design Center, the restored home will highlight Mitchell’s life and career and feature meeting space, a gallery, and offices.

Wanda G. Best, executive director of the Upton Planning Committee, previously told The Baltimore Banner that she hopes Upton will become a destination because of its African American history. A 2026 master plan listed strengthening heritage tourism, preserving the character of the neighborhood and revitalization without displacement and mass gentrification as its goals.

Philip J. Merrill, CEO of Nanny Jack & Co. LLC, an African American heritage consulting firm, said the preservation projects are “long overdue” for West Baltimore. Merrill has done extensive research on Old West Baltimore throughout his career and said it’s “ripe and rich” enough to have similar projects happening on a consistent basis.

“Baltimore was a hub of activity, and my hope is that with the right money, focus and leadership, that the community will be sustainable and thriving, where people will want to come and reinvest and make it the jewel that it was back in the day,” Merrill said, adding that every deal struck in Old West Baltimore is a true reminder of its value.

Merrill said there needs to be a marker system — a collection of descriptive plaques and other signage — in West Baltimore that’s properly funded and researched so people can take self-guided tours and get introduced to the history.

In Upton’s Marble Hill, Baltimore Heritage and the Lillie Carroll Jackson Civil Rights Museum conduct tours of the museum and neighborhood landmarks.

Hathaway agreed there’s steady momentum with historic properties, but said more work to be done to preserve them.

“I think we should be proud of our history, and we should do all we can to restore these amazing properties,” Hathaway said. “We shouldn’t look at them as eyesores, but look at them as opportunities.”