A Philadelphia Inquirer headline recently caught my eye: “Scientists Earn Penn Prestige–and Money.” According to the piece, the University of Pennsylvania brought in over $1.2 billion in licensing revenue in fiscal 2022, a total that dwarfs the amount garnered by all other U.S. universities. This staggering figure represents money earned through payments made by private sector companies seeking to capitalize on the technical and scientific innovations of Penn doctors and scientists. The Covid-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna using techniques developed by freshly-minted Nobel laureates Drew Weissman and Katalin Kariko represent a large chunk of the school’s current earnings.

Penn intends to use this windfall to expand its research into emerging medical technologies, including roughly $350 million to build new laboratory space. Having recently finished reading Laura Wolf-Power’s new book, University City: History, Race, and Community in the Era of the Innovation District, published by University of Pennsylvania Press, I recognized that the repercussions of Penn’s planned expansion are likely to spread beyond the school’s existing footprint and into whichever residential neighborhood lies closest to these envisioned new labs.

Eds and Meds have been lauded as the surefire means of reviving and invigorating urban areas, particularly in formally industrial cities like Philadelphia, the erstwhile Workshop of the World. Wolf-Powers takes a deep dive into the processes that enabled Penn and Drexel University to dramatically reshape parts of West Philadelphia. She also examines the efforts made by residents of university-adjacent neighborhoods to maintain community cohesion in the face of aggressive institutional growth.

Erasure of the Black Bottom

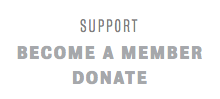

Plans for the urban renewal area around University City circa 1960-70. | Image courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

The term “University City” was first used in a 1958 City Planning Commission document, as Philadelphia leaders contemplated ways to transform the economy. In 1963, the Redevelopment Authority laid out a blueprint for the creation of a science and research center located in the area between Penn and Drexel. City planners, government officials, and university leadership embraced this plan to build the University City Science Center, a series of office buildings on a tract of land running from 34th Street to 40th Street both north and south of Market Street. The only thing standing in the way of this vision was a Black working-class neighborhood of over 3,400 people, 1,400 homes, and dozens of businesses known as the Black Bottom.

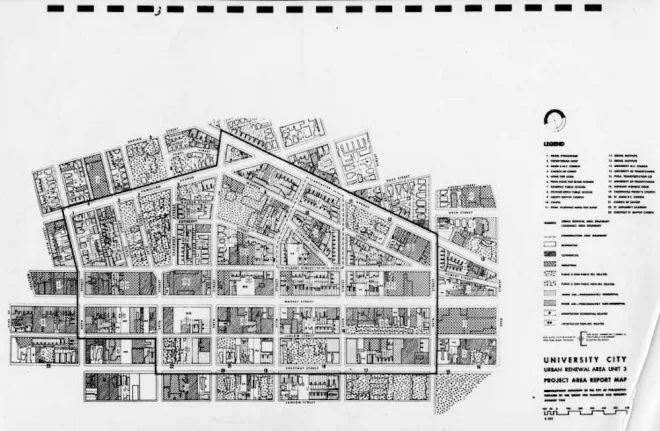

This photograph from 1975 shows the heart of Black Bottom, a thriving, predominantly African American neighborhood in West Philadelphia, along Market Street between 34th and 40th Streets after area homes and businesses were demolished. | Photo courtesy of Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

Given that this was the era of slum clearance and aggressive urban renewal, the Redevelopment Authority’s plan called for a complete eradication of the Black Bottom neighborhood. In response, residents staged a multi-day sit-in at the office of Mayor James Tate. They demanded that plans be revised to save some existing houses and to require the construction of new affordable units on the cleared land. They also pressed for representation on the board of the West Philadelphia Corporation, a Penn-led consortium that was spearheading the University City Science Center initiative. Although the Redevelopment Authority acceded to some of the demands, the West Philadelphia Corporation pushed forward as if no such agreement had been reached.

Neighbors gather in 1970 to visit the newly rehabilitated houses on the 3600 block of Warren Street. | Photo courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

Wolf-Powers describes the various efforts of community members to resist the extermination of their neighborhood—from enlisting the help of civil rights and church groups, to written appeals to local and federal leaders, to filing lawsuits against the Redevelopment Authority, the City Planning Commission, and the West Philadelphia Corporation. However, with federal urban renewal funds pouring in, enthusiastic support among City officials, the effective use of eminent domain laws, and the strong arm of leading academic institutions pushing things along, the Black Bottom was leveled beginning in 1967. One block of Warren Street, and the memories of the people who had called the neighborhood home, was all that was left of the Black Bottom.

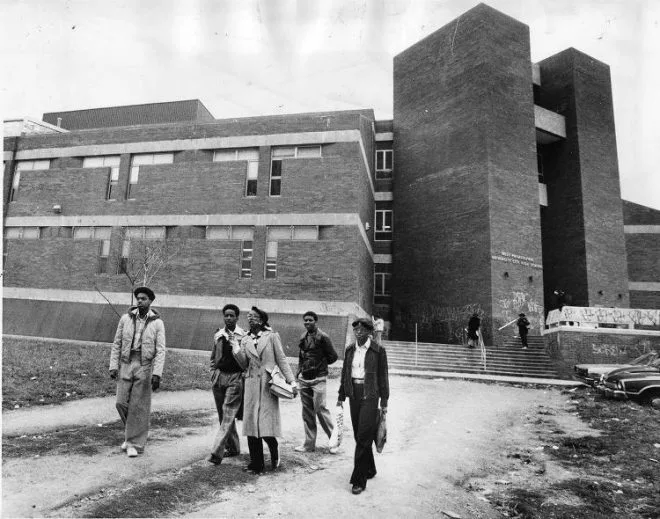

Students of University City High School in 1977. | Photo courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

Adding insult to injury, land that had been set aside for new housing was instead used to construct University City High School (UCHS). It was envisioned as a magnet school specializing in science and technology that would attract an integrated student body. Although it was equipped with a swimming pool, technology labs, and a darkroom, UCHS never fulfilled its stated goals. With lackluster support from Drexel and Penn, the school was plagued with the ills typical of comprehensive high schools in the chronically underfunded school district. In 2013, UCHS was demolished.

A New Approach to University-led Development

In 2017 Drexel University broke ground on redeveloping the former Bulletin Building and adjoining parking lot at 3001 Market Street for Drexel Square, the first project for Phase 1 of Schuylkill Yards. | Photo: Michael Bixler

The 21st century gave rise to a new paradigm of urban development: the innovation district. In this model, real estate developers take the lead in creating live/work/play spaces meant to attract knowledgeable, talented, and entrepreneurial people whose combined efforts will, hypothetically, produce wealth for the cities in which they are situated. Developers typically work with anchor institutions that are firmly rooted within the given city. While Penn was the prime mover in the University City Science Center project, Drexel has taken the lead in seizing this newer form of university-led development.

Wolf-Powers explores how Drexel’s two innovation districts, UCity Square and Schuylkill Yards, have engaged with the neighboring residential communities of Powelton Village and Mantua. Much of the book focuses on Schuylkill Yards, a $3.5 billion project designed to transform vacant land, parking lots, and under-utilized buildings into a thriving hub of jobs, homes, and green space. Unlike the slum clearance of an earlier era, neighboring communities have not been threatened with complete destruction. The power differential between the real estate developers and their university partners on the one side and the residents and civic organizations on the other, however, remains vast.

Even before the inception of the innovation district projects, Drexel-adjacent neighborhoods felt threatened. Huge growth in Drexel’s enrollment led to many single-family homes being subdivided into student rentals, changing the character of Powelton Village and encroaching on Mantua as well. Once UCity Square and Schuylkill Yards were announced, the situation was exacerbated as the multiple challenges associated with gentrification ensued: land speculation, increased tax assessments, foreclosures on the homes of long-term residents, and disruption of the fabric of a community.

The Neighborhoods Step Up

The proposed future view of Schuylkill Yards looking northwest towards University City. | Rendering: SHoP Architects and West 8

Thanks to a long history of community organizing and civic engagement in Powelton Village and Mantua, residents did not hesitate to make their voices heard. As Wolf-Powers explains, Powelton Village is a community of mostly progressive, highly educated, relatively affluent white people–in other words, the type of people who have the time, connections, and expertise to organize themselves politically to fight for their neighborhood. She spends much more time detailing the emergence of groups like the Young Great Society and the Mantua Community Planners that were led by Herman Wrice and Andrew Jenkins in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The legacy of these organizations is a working-class Black community that has the leadership, experience, and agency to demand a seat at the table.

When Councilmember Janine Blackwell refused to sign off on the Schuylkill Yards project without a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), the Mantua Powelton Alliance formed to negotiate on behalf of the neighborhoods. Drexel president John Fry had described Schuylkill Yards as a project that “will benefit thousands of low-income families without disrupting the fabric of neighborhoods.” Fry also asserted that “Schuylkill Yards will be an inclusive-growth development that will open doors and create opportunities for residents in all of our surrounding neighborhoods.” Ironically, however, Drexel did not participate in the CBA negotiations.

The $287 million West Tower at Schuylkill Yards is currently under construction. | Rendering courtesy of Brandywine Realty Trust

Brandywine Realty Trust, the Schuylkill Yards developer, represented the interests of the project itself. Thus, an inherent unfairness was built into the CBA process: community volunteers were pitted against paid corporate staff. The community volunteers did the best they could to extract jobs, resources, amenities, financial protection from escalating property values, and other benefits for their neighborhoods. Nonetheless, as Wolf-Powers Mantua–Powelton Alliance sums it up in her book, “The CBA process was an important source of public sector leverage over Schuylkill Yards, and a lever that Councilmember Blackwell intended to use. But the community-based organizations were negotiating with an organization whose primary obligation was to its shareholders.”

Case in point: when community representatives from Mantua did some research in advance of the negotiations, they learned that similar groups had received two percent of the total cost of major development projects. Along with their Powelton Village counterparts, they asked Brandywine Realty Trust for that same percentage which amounted to $72 million. Eventually, Brandywine agreed to give the community groups only $3.1 million. This is a simplification of a complex agreement, however. A comment from one of the Powelton Village representatives quoted in Wolf-Powers’ book succinctly described the fundamental problem with the process: “The politicians are happy to let us fight it out, let the volunteers go up against the developers. There is nothing wrong with developers—they’re not terrible people. But there needs to be somebody other than schoolteachers and artists to line up against these people.”

A Questionable Strategy

Lots being cleared in 1968 on the 3600 block of Filbert Street for the redevelopment of University City. | Photo courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

There is another salient unfairness in the innovation district model: it only works for developers if they are granted substantial tax breaks and government subsidies. The land on which uCity Square and Schuylkill Yards are built is leased to the developers by Drexel, a non-profit. The ground lease payments are thus exempt from federal corporate income tax. The innovation districts sit on land that has been designated as both a state and a federal Opportunity Zone which shields the developers and future occupants from numerous taxes. Philadelphia’s ten-year tax abatement also applies to these projects. Millions of dollars of state Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program funds were granted to the developers. Given this scenario, it is hard to understand how the building of an innovation district is likely to achieve the goal of reviving the host city.

University City: History, Race, and Community in the Era of the Innovation District is intended mainly for an academic audience. Wolf-Powers writes in clear prose, and I learned a great deal despite my lack of formal training in urban economics or city planning. I include this disclaimer because I know I have oversimplified the book’s content. Wolf-Powers does not depict Penn and Drexel as forces of unmitigated oppression and greed. She praises, for example, the work of Drexel’s Dornsife Center for Neighborhood Partnerships and the Lindy Center for Civic Engagement. She does, though, make it clear that the surrounding communities deserve much more than they have received during the decades of massive growth of eds and meds. She also argues that the time, effort, and care that people put into their homes and neighborhoods is extremely valuable, even if these things do not come with a price tag.

When Penn decides to use its enormous licensing fee royalties, and as Drexel continues to build its innovation districts, these institutions would be well-advised to see their neighbors as assets to be supported rather than as nuisances to be shooed away.