The United Nations recognizes solitary confinement—which it defines as “confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact”—as being akin to torture. In 2015, the UN adopted guidelines seeking to end the use of prolonged solitary confinement, as well as any solitary confinement for prisoners with disabilities that “would be exacerbated by such measures.”

Still, solitary persists in nearly every US state. A 2022 report from Yale Law School estimated that more than 10 percent of incarcerated people in Utah and Nevada are in restrictive housing, a category that generally includes solitary. (Uses of these terms vary slightly, but the American Correctional Association similarly defines restrictive housing as keeping incarcerated people in their cells “at least 22 hours per day” and away from the general prison population. )

Many states report having people with severe mental illnesses in restrictive housing, despite research clearly demonstrating that, as the UN guidelines suggest, solitary confinement often exacerbates the symptoms of psychiatric disabilities.

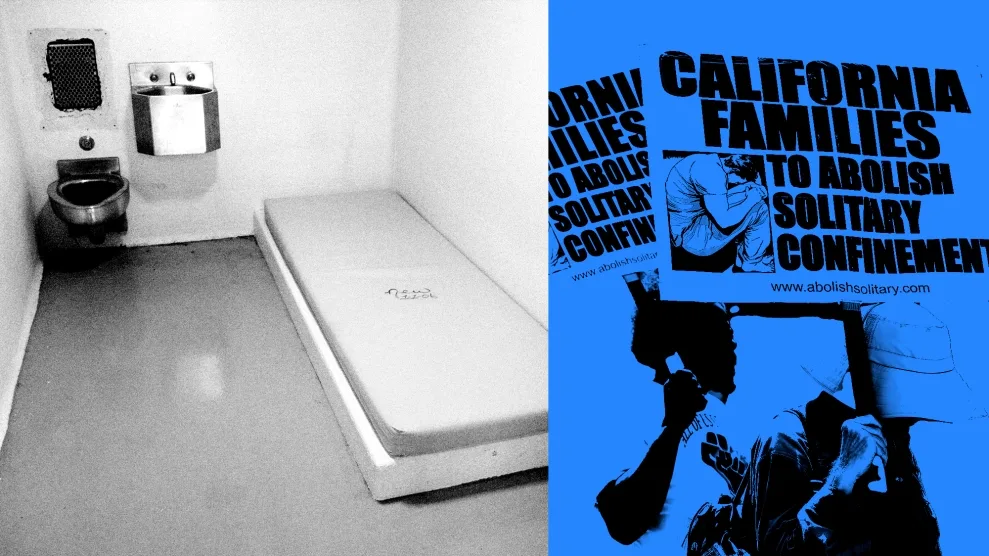

Even in the most progressive states, the power of a governor’s veto can still squash efforts at reform. As in Connecticut, lawmakers in California experienced this first-hand in 2022 when Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) vetoed the Mandela Act, which would have placed new restrictions on solitary confinement. But they are trying again.

In late May, AB 280—the revived Mandela Act—passed the California Assembly. The bill, which could soon pass the state Senate, would limit the length of solitary confinement for all incarcerated people and would ban it for disabled people, pregnant people, and those under 26 or over 59 years of age.

The fight to end or limit solitary is not just a disability rights issue, but a racial justice issue, as well. A November 2021 research article, for instance, estimated that nearly 1 in 100 Black men in Pennsylvania has been held in solitary for a year or longer by the age of 32.

“What disability justice encourages us to do is to think…about how race can combine with disability to produce increased vulnerabilities to solitary confinement,” says Jamelia Morgan, a law professor and director of Northwestern University’s Center for Racial and Disability Justice.

An October 2020 study, for example, looked at the physical impacts of solitary confinement in Washington state, where Black and Latino people are more likely to be in solitary. Many interviewees spoke about the musculoskeletal pain they experienced while being held in a small area that limits movement and the near-impossibility of getting medical treatment.

“The popular critique of solitary confinement largely emphasizes its negative mental health effects, which is of course important,” says Justin Strong, a San Jose State University assistant professor who was the study’s lead author, “but we should consider the fuller picture of how people experience adverse physical health outcomes too.”

One of the people pushing for AB 280 is Vanessa Ramos, a community organizer with Disability Rights California, a sponsor of this legislation. After experiencing trauma in her childhood, she was misusing drugs by the age of 13 and had bouts of depression. At 19 years old and a new mother, Ramos was incarcerated in a Los Angeles prison’s basement, while also going through withdrawal.

During her months-long incarceration, Ramos recalls spending days at a time in solitary, but due to trauma, the exact lengths of these periods are blurry.

Ramos does remember that she was not asked any questions about her mental health when she entered the prison.

“You get booked,” Ramos says. “I was faced with the carceral experience that further traumatized me.”

Years later, she has been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and also lives with post-traumatic stress disorder. Ramos did not know at the time that incarcerated people with disabilities have the right to advocate for reasonable accommodations—such as having some natural light—under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

After getting out of prison, Ramos has used her experience in the criminal justice system to fight for others, which led her to her current role. Learning about yoga—she has received some training through the Prison Yoga Project—has also helped her heal in some ways.

But solitary confinement still haunts her. She is not comfortable having doors locked. She doesn’t like surprises, so her family knows to not throw surprise birthday parties.

Even in states that have passed legislation to reform confinement, not all the required changes have actually been made. This is the case in New York, which passed a law in 2021 to limit solitary. An April 2023 class action lawsuit claimed that the state has not been properly implementing the legislation, including failing to stop solitary confinement from being used for more than 15 consecutive days. One inmate, Fuquan Fields, said he was ordered to be sent to solitary for 120 days—eight times the legal limit under New York’s Humane Alternatives to Long-Term Solitary Confinement Act.

But the fight in Connecticut gives reformers hope. After Lamont enraged advocates and survivors with his veto, Stop Solitary CT and its supporters redoubled their efforts. Bernardi Guzman testified in front of a legislative committee once again, telling lawmakers that solitary confinement “drives the human spirit to despair.” In May 2022, they finally succeeded, when Lamont signed a bill similar to the one he’d killed.

Activists in California are hoping their governor will soon make the same decision.

Images, from left: John Doman / MediaNews Group / St. Paul Pioneer Press/Getty; Michael Macor/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty