U.S. political violence driven by new breed of ‘grab-bag’ extremists

A new breed of extremist has sparked the deadliest wave of U.S. political violence in decades. These self-made radicals, mixing right-wing conspiracy theories and marginal beliefs, forgo logic and coherence in favor of personal grievances.

Before he committed mass murder in Colorado late last year, Anderson Lee Aldrich was a lively presence among a group of friends who regularly assembled online for hours to chat, play video games and trade internet memes.

The four irreverent young men shared a desire to mock “cancel culture” and laugh over “dumb, silly stuff,” Gilbert Arroyo, one of the friends, told Reuters. But over the roughly three years of their gatherings, the memes and quips Aldrich shared grew increasingly racist, homophobic and violent, according to three of the gamers and a Reuters review of online content that Aldrich assembled.

Despite his vitriol, the friends said, Aldrich’s jokes were more scattershot humor than ideological manifesto. They never perceived him to be espousing any particular belief system or aligning with specific hate groups or political causes.

They were shocked, then, when Aldrich, wielding an assault rifle and a handgun, entered Club Q, a gay nightclub in Colorado Springs, and opened fire last November. The 22-year-old, who once dreamed of joining the military, killed five people and injured 22. He pleaded guilty in June to murder charges and is serving five consecutive life terms in state prison.

Arroyo said he never expected Aldrich to act upon the hate and violence his joking conveyed. “Nothing was meant to be taken seriously,” Arroyo said in an interview. “Nobody should have been killed.”

Aldrich is an example of a new and troubling type of violent American extremist, according to law enforcement officials and political scientists: the grab-bag radical.

Past perpetrators tended to fall into two broad categories.

One includes militants recruited and trained by others to defend a cause, such as the anti-government beliefs of far-right militias. The other was a previous breed of “lone wolf” terrorist, obsessed and informed by a clear issue that motivated attacks, like the bombings by Ted Kaczynski, the “Unabomber,” because of his opposition to technology.

Aldrich, by contrast, embodies a novel extremism forged distinctly by today’s polarized politics, fragmented online discourse and prevalence of fictional narratives. Like other actors behind a wave of political violence analyzed by Reuters, Aldrich wove his own brand of fanaticism from disparate strands of conspiracy theories widely circulating on the internet.

Pulling from a hodgepodge of marginal beliefs – in Aldrich’s case homophobic, racist and antisemitic ideas he later featured on a website – these radicals often eschew firm creeds. Instead they embrace whatever brew of notions, no matter how divergent, blends with their particular grievances.

“I don’t really know what was going through his head.”

There is “a mixed bag approach to their beliefs,” said Brian Hughes, an assistant professor at American University in Washington, D.C., and co-founder of a program that studies extremism there. With the scattered, often haphazard nature of online content, “you can string together all kinds of concepts in a way where logic doesn’t have to factor into it at all, much less ideological consistency.”

Reuters recently documented the most sustained spate of political violence in the United States since a decade of upheaval that began in the late 1960s. To date, the news organization has identified at least 232 violent incidents fueled by political motives since the storming of the U.S. Capitol by supporters of former President Donald Trump on Jan. 6, 2021. The events range from riots to brawls at political demonstrations to beatings and murders.

The incidents involve violence emanating from across the political spectrum, including dozens of cases of substantial property damage by leftists at political demonstrations. But of the 22 fatal incidents among the total tally, involving the deaths of 44 victims and 11 attackers, most were attributed to assailants, like Aldrich, who expressed beliefs associated with the extreme right, Reuters found.

In 15 of those attacks, in which 38 victims and seven attackers died, the perpetrator had articulated far-right beliefs, many of them targeting racial, sexual or other minorities. Only one fatal incident – the 2022 stabbing of a journalist by a public administrator in Nevada – was carried out by an assailant clearly identified with the left.

It’s impossible to say in these cases that political rhetoric itself led to killing. And history shows that violence can arise from the left, right or any other political position.

But law enforcement officials and researchers interviewed by Reuters say that the promotion of once marginal conspiracy theories by prominent Republicans, especially Trump, has pushed fringe ideas into the mainstream. That amplification of far-right rhetoric can make it easier for people with violent propensities to encounter those ideas, embrace them and justify their deeds as ideological or political.

Of the far-right assailants in the fatal cases reviewed by Reuters, at least 12 had researched or promoted extremist beliefs on the internet. At least six were ardent Trump supporters.

“Extremist narratives have gained a sense of mainstream credibility and legitimacy because of who’s promoting the ideas,” said Michael Jensen, who runs the University of Maryland’s Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States project.

Trump has appeared to condone violence repeatedly in recent public statements.

At an event in late September, he said federal troops should shoot shoplifters. Days earlier, on social media, he wrote that Mark Milley, whom he had appointed chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, had been “treasonous” and that “in times gone by, the punishment would have been DEATH!” In an interview with a right-leaning website, he employed language often used by racist groups, saying undocumented immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country.” And during a Veterans Day speech last week, he referred to political opponents as “vermin,” a term historians say has often been used by autocrats in the past to dehumanize and provoke violence against rivals.

Steven Cheung, a spokesman for Trump, didn’t respond to questions from Reuters about the former president’s remarks and the impact of his rhetoric. Milley declined to comment.

Some of the killers in cases reviewed by Reuters acknowledge being swayed by rhetoric.

Rory Banks, a convicted murderer from Wheaton, California, told Reuters Trump’s 2020 loss led him to online chat groups and to embrace the fabricated theories of QAnon, which holds that a cabal of leftist, Satanic pedophiles control the U.S. government. In a telephone interview from prison, Banks said his obsession led him to find convicted sex offenders near his home and, in May 2021, kill one.

His entry point was “‘Stop the Steal,’ stuff like that,” he said, referring to the false belief, fomented by Trump himself, that the former president was cheated at the ballot box. “I got onto the message boards, and I met other people through social media, and it didn’t take long.”

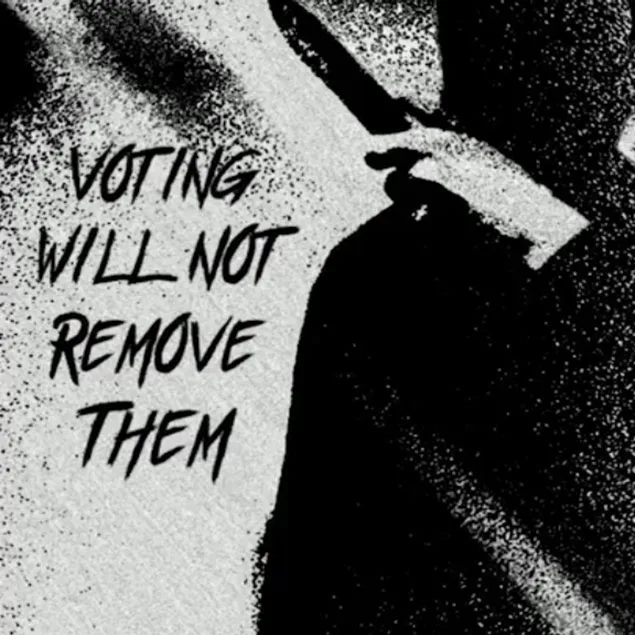

One reason people get radicalized online is that meme culture can quickly reduce issues to a punchline or a call to arms. And by circulating entirely online, with no checks on factuality or origin, memes and the joking around them can convey messages and provoke reactions with none of the back-and-forth that happens in person, let alone the learning acquired through research or deep study.

“These people, who take this amount of content that’s packaged in this particular form of humor, they are desensitized,” said Jacob Ware, a Washington-based security specialist and research fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank. The breezier the chitchat, he added, the easier for budding extremists to overlook the implications. “When you’re so immersed in this meme space,” he said, “the victims stop being human.”

Aldrich, Banks and at least seven more of those charged or convicted in murders reviewed by Reuters had at some point claimed to suffer or were treated for mental health issues, according to court documents, police records and other documentation. But those who study extremism say psychiatric problems alone rarely induce political violence.

“No one radicalizes in a vacuum,” says Jensen, the Maryland political scientist. “They do it within social networks.”

To understand this path toward extremism, Reuters examined the history of the 15 assailants whose writings and statements detailed the sources and tenets of their far-right radicalization. Reporters interviewed more than 50 law enforcement officials, attorneys, relatives and friends of the perpetrators, among others. The news organization also mined their internet history and social media posts, as well as police reports, court records and other documents.

The perpetrators share some common traits:

None belonged to any hate group or other extremist organization or adhered to a single, distinct ideology.

At least half consumed or promoted some mix of white supremacist and antisemitic material online. Others followed QAnon, anti-government or homophobic conspiracy theories. Some also embraced misogyny and the male supremacy movement.

Several were influenced by so-called Great Replacement Theory – a belief that “elites,” often Jews, are orchestrating the demise of white culture through immigration, Black empowerment, feminism and LGBTQ rights.

The extremists’ motives are incomprehensible to relatives of those they’ve killed.

“I don’t really know what was going through his head,” said Stephanie Clark, whose sister, Ashley Paugh, worked with foster children before Aldrich murdered her at Club Q. “She would have done anything for anyone. She would have tried to help him.”

“The end of the world”

From the late 1960s and through the mid 1970s, many extremists joined groups aligned with the left, particularly spurred by the civil rights movement and opposition to the Vietnam War. By the 1990s, the pendulum had swung right. Militias and white power groups became a source of radicalization against government authority.

Trump’s embrace of conspiracy theories dates back at least to his promotion of the falsehood that former President Barack Obama wasn’t born in the United States. In his successful 2016 campaign, Trump vilified immigrants, said Mexico was sending criminals across the border, and suggested that the father of Republican Sen. Ted Cruz, an opponent, was linked to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

“That role that Trump played in 2016 is what was truly the accelerant” in mainstreaming fringe conspiracy theories, said Matt Kriner, a director at Middlebury College’s Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism, in Monterey, California. With increasingly radical rhetoric, he added, dissatisfied citizens are more likely to believe that “the only solution is violence.”

An August survey by the Public Religion Research Institute, a nonprofit research organization based in Washington, found that 13% of Democrats and one-third of Republicans believe “true American patriots may have to resort to violence to save our country.” The overall 23% of respondents who agreed marked an increase from 15% in a similar poll in 2021.

FALSE BELIEFS: After he killed his wife, police documented how Troy Burke, a building contractor in Michigan, grew increasingly delusional, embracing online conspiracies after the 2020 election. REUTERS/Gratiot County Sheriff

In Elwell, a town in central Michigan, Troy Burke, a building contractor, came to believe online conspiracy theories after the 2020 election. The United States, he told police, was headed for civil war. QAnon believers were an “elite group,” “battling it out for our freedom, for Trump, to save our republic,” he said, according to police records.

By early 2021, Burke, then 44 years old, came to believe that his wife, Jessica, was a transgender person fathered by President Joe Biden. He also believed that Jessica, a 29-year-old shop employee, was an “asset” of the Central Intelligence Agency. “If I didn’t put three rounds in the back of her head,” he told investigators, “it was the end of the world.”

On Jan. 27, 2021, he shot her dead. A court last year found Burke not guilty by reason of insanity. He is now detained at a Michigan state psychiatric facility. His attorney, Sarah Huyser, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Because they don’t assemble and aren’t affiliated with organized groups, today’s extremists can radicalize in isolation and raise little suspicion. And no matter how troubling their online activity may be, much of it is protected as free speech under the U.S. Constitution. Even after an attack, police often find the perpetrator “doesn’t fit into the neat category that they’re used to working on,” says John D. Cohen, a former assistant secretary for counterterrorism at the Department of Homeland Security.

Nathan Allen, a 28-year-old physical therapist, killed two Black people during a barefoot rampage in Winthrop, Massachusetts, on June 26, 2021. Until that day, local police told Reuters, Allen lived a quiet life, not even his wife suspecting he embraced racist theories or, ultimately, could commit murder. On Facebook, he posted loving notes about his wife and their pet rabbit, and urged others to adopt bunnies, too.

With no criminal record, and no violence in his past, he “went unchecked and unnoticed,” Winthrop Police Chief Terence Delehanty said.

The night before the murders, Allen and his wife, Audrey Mazzola, attended a party. She decided to stay at the host’s house. The next day, police records show, Allen texted Mazzola, who said she would brunch with her friends and return home.

“Cutie,” he responded.

Mazzola didn’t respond to Reuters requests for an interview; a man who identified himself as her father in a telephone call said the family wouldn’t speak with reporters.

Minutes after the texting, Allen walked out of their apartment. Wearing no shoes, he carried two Smith & Wesson handguns, ammunition, and several books and journals. Nearby, he stole a large truck. Flooring the accelerator, he sped into town, weaving across lanes at high speed. Clipping another vehicle, he crashed into a building.

Bloodied, he left the vehicle and walked past a number of onlookers, all white.

Moments later, he approached Ramona Cooper, a 60-year-old grandmother and Air Force veteran, and shot her three times. She was the first Black person he encountered. Hearing the commotion from his apartment, David Green, a retired state trooper, ran outside. Allen saw Green, a 68-year-old African American, and shot him seven times.

Both died.

A police officer arrived and told Allen to drop his gun. Allen raised his pistol and the officer fired 11 times. Allen died at a hospital.

When police searched his apartment, they found racist screeds handwritten on the unused pages of old school notebooks. More of his writing, reviewed by Reuters, featured antisemitic drawings and complaints that women, including his wife, didn’t understand white male superiority.

White men are “apex predators,” he wrote. “All its gonna take is a lil nudge, then whites in the US will snap.”

After the murders, radical right cyberspace rang with praise.

On the Telegram messaging app, an anonymous user created a poster, adorned with crosses, hailing “Saint Nathan Allen.” Because police had speculated that Allen may have been targeting a local synagogue before crashing and changing plans, the poster read: “We have to admire his ability to adapt and improvise under high stress and unfathomable pressure!”

“I’d be better in jail or dead”

Aldrich, the gamer turned mass killer, had telegraphed some of his bigotry. He had also had trouble with the law, spending nearly two months in jail after threatening to kill his grandparents.

Born in California in May 2000, Aldrich had an itinerant, volatile home life, according to friends, court documents and testimony. His parents divorced while he was a baby. His father, a mixed martial arts fighter and later an actor in the adult-film industry, moved out.

With his mother and, later, her parents, Aldrich lived in cities across California and Texas, where he finished high school. Afterward, they settled in Colorado Springs.

Along the way, Aldrich was bullied, often because of his dad’s porn career, the father, Aaron Brink, told a San Diego television station after his son attacked Club Q. He urged Aldrich to fight back, he said. “I praised him for violent behavior really early,” he told the station.

Brink died earlier this year.

Aldrich’s mother, Laura Voepel, had legal problems.

In 2008, court records show, she was convicted of public intoxication in California. In 2013, she was convicted of criminal mischief for burning a house in Texas. Through her attorney, Carrie Thompson, Voepel declined to speak with Reuters.

In testimony to a Colorado court, following the 2021 threatening of his grandparents, Aldrich said he suffered unspecified abuse as a young child. He also said his home life caused mental health problems.

“I had been refusing to take care of myself, refusing to be diagnosed with illness and refusing to take medicine,” he said. It isn’t clear whether any doctor formally diagnosed him with mental illness.

In 2019, Aldrich enrolled in a Colorado college but never attended. He hoped to join the military but didn’t enlist because he doubted he could pull his own weight. “How could I take care of a brother in arms if I couldn’t even take care of myself?” Aldrich told the court.

“We have to admire his ability to adapt and improvise under high stress and unfathomable pressure!”

That same year, Aldrich met his gamer buddies on Discord, an online platform where users can text and place audio and video calls. The platform, which has a broad variety of users, is known to be popular with many in the alt-right, as the racist, nationalistic and other extreme elements of the right have come to be known.

In a statement, John Redgrave, Discord’s vice president of trust and safety, said the company has a “zero-tolerance policy against violent extremism,” at times “removing content, banning users, shutting down servers, and engaging with law enforcement.” Redgrave didn’t address specific questions about Aldrich and his friends.

The group was far flung. Arroyo, the friend who said their banter was only for laughs, lives in Ohio. Another logged in from Illinois. The fourth lives in Australia.

Still, they grew close, bonding over games like Sea of Thieves, in which players sail pirate ships. In time, “Andy,” as the gamers knew him, opened up. He told them about rocky family relationships and struggles with depression, two said.

“Andy was someone I considered to be my best friend,” Luke Simpson, the gamer in Australia, told Reuters in a written response to questions.

For two months in 2021, Aldrich left Discord. He had been jailed.

Since the move to Colorado, Aldrich lived in a house with his grandparents. His mother lived in a nearby apartment.

In June 2021, police records and court documents show, Aldrich grew furious and pulled a pistol when his grandparents said they wanted the family to move to Florida. “You guys die today,” he said, according to police records.

The grandparents, Jonathan and Pamela Pullen, didn’t respond to emails or a letter from Reuters requesting comment.

Aldrich, the Pullens told police, said a move to Florida would ruin his plans to conduct a mass shooting. He brandished a box of chemicals from the basement, they said, and boasted the contents could destroy a government building. Reuters couldn’t determine the box’s contents. Investigators later described them as “consistent with bomb-making materials,” a police document shows.

It’s unclear whether Aldrich on other occasions expressed plans for a mass shooting.

Terrified, the Pullens told Aldrich they wouldn’t move. He went to his mother’s apartment and the grandparents called police, who dispatched a SWAT team. He surrendered, hands in the air.

Prosecutors charged Aldrich with kidnapping and menacing. His mother and grandparents urged the court for a second chance. Aldrich was released on bail after seven weeks in jail. When the family refused to cooperate with further testimony, prosecutors dropped the charges.

Back on Discord, Aldrich told his friends what happened. “People make mistakes,” Arroyo said they told him. “If you need anybody, just come to us.”

Aldrich confided further about his woes.

And he began sharing more troubling content.

Nick Brooks, the friend in Illinois, told investigators that Aldrich used “the N word a lot” and used a slur for gay people, according to court transcripts. Brooks, in an email via his wife, declined to speak with Reuters.

In the summer of 2022, Aldrich told the group he wanted to build a website to “promote freedom of speech,” Arroyo said. The site, now defunct, featured an assortment of anonymous posts, far-right videos, memes and messages. Reuters reviewed its contents through web archives.

One image featured Pepe the Frog, a cartoon mascot adopted by white nationalists, stabbing Black people. Another showed a rainbow flag, the symbol of gay pride, bearing a swastika. One video, calling for the killing of Blacks, Jews and elected officials, had also inspired the shooter who in May 2022 killed 10 Black people at a supermarket in Buffalo, New York, court records show.

By autumn, Aldrich appeared increasingly despondent.

Three days before his assault on the gay nightclub, he wept on a Discord chat. He told the friends his mother was breaking objects in the apartment. “I’d be better in jail or dead,” Arroyo said he told them.

Shortly afterward, Aldrich sent Simpson, the friend in Australia, a street map of the area around Club Q. He didn’t express any plan to attack it, Simpson told Reuters. Their last conversation was about video games.

“The map didn’t lead me to think I’d see my friend behind bars,” Simpson said.

In a court filing by the attorneys who handled his guilty plea, Aldrich noted, without elaborating, that he was non-binary and wanted to be addressed by they/them pronouns. His attorneys, Michael Bowman and Joseph Archambault, didn’t return calls or emails seeking comment.

The night of the attack, Arroyo said, Aldrich texted him at around 9 p.m., three hours before he entered the nightclub.

“I love you man,” Aldrich wrote.

“Are you ok?” Arroyo answered.

Aldrich never responded.

Politics of Violence

By Ned Parker, Peter Eisler, and Joseph Tanfani

Art

direction: John Emerson

Edited by Paulo Prada