Following his trial in Denver, Timothy McVeigh — convicted of killing 168 people in the 1995 bombing of the Murrah Building in Oklahoma City — was sent to a federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana. Every few weeks, Ellis Armistead visited him on death row. A private investigator in the Mile High City, Armistead was assisting the attorneys working on McVeigh’s appeals process, which lasted several years. By late spring 2001, McVeigh had decided to drop his appeals against his lawyer’s advice, not wanting to die in prison decades later.

“I understand why he did this,” Armistead says in his slow Southern drawl. “I’ve had two clients commit suicide in jail.”

The investigator found McVeigh calm and considerate, treating corrections officers well and regularly asking about Armistead’s staff. Once the inmate began corresponding with author Gore Vidal and following his March 2000 60 Minutes interview — Armistead was present for that — he also noticed McVeigh’s growing narcissism. He saw no remorse in the young man.

“I observed the monster in him,” he says, “and the human being. Sometimes there’s a fine line between the two.”

Before his death, McVeigh confided that he had a “higher being” — a remark that left Armistead wondering if he could say the same thing about himself. One of his tasks was traveling to upstate New York to inform the condemned man’s father, William, that McVeigh would soon be executed.

“It was a snowy night in Buffalo when I drove out to Bill’s house,” Armistead recalls. “He was a great guy. When I told him what was about to happen, he said, ‘I love my son, but I believe in the death penalty. Do you want a highball?’”

The investigator was with McVeigh in Indiana twenty minutes before he received the lethal cocktail. He’d asked the P.I. to be a witness at his execution, but Armistead had declined.

“I could deal with him better once he was gone,” he remembers. “I pulled him off the gurney.”

An autopsy wasn’t performed because people were clamoring to buy McVeigh’s body parts, even strands of his hair, and the authorities didn’t want to risk that. After many funeral homes had turned him down, Armistead found a mortuary that would carry out the cremation. One of his assistants put the ashes in her backpack and took them to the airport; on the plane she sat next to a journalist who’d covered the execution. He began telling her about the widespread rumors that the ashes had immediately been flown out of the country.

“He didn’t know that they were right under her seat,” Armistead says. “Sometimes in this job, you have to laugh to keep from crying.”

Back in Denver, he took the ashes home, where his employees were unwinding after the long McVeigh ordeal with pizza and beer. When his wife, a trauma nurse in an intensive-care unit, found out what was in the backpack, she was livid.

“Get that out of here,” she told him, and he did.

This wasn’t the first time he’d provoked his wife with his involvement in a high-profile case. He’d once mistakenly put a victim’s hands in the freezer at home.

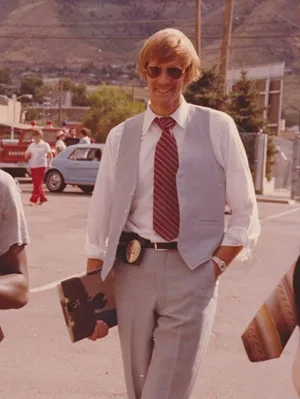

Ellis Armistead was with Timothy McVeigh just before the Oklahoma City bomber was given a lethal injection.

Wikipedia CC

By 2001, his marriage was starting to teeter. Armistead was 51 and had been in the criminal justice system for 28 years, working for both law enforcement and defense teams. A decade earlier, he’d begun having severe nightmares and violent flashbacks. He couldn’t watch movies, TV shows or documentaries featuring bloodshed. Some nights he thrashed so hard he had to sleep on the couch. In the first years of his career, police departments had offered little or no help for those suffering from emotional trauma, in part because acknowledging such things might open them up to liability issues (and many officers didn’t want to admit to having these problems).

Knowing something was wrong and that he needed professional help, Armistead sought out a therapist. When he finished describing his employment situation, she replied, “You need to find someone else. I can’t handle this.”

She couldn’t handle him being called to the worst crime scenes and dealing with the people most affected by a tragedy — those who couldn’t comprehend or accept what had just happened to a loved one, or those who couldn’t believe what a loved one had done to others. In virtually every situation, Armistead was a steady presence when others struggled to cope. But off duty, especially at night, the nightmares and flashbacks kept coming. Sometimes, he drank too much or had memory lapses or dark thoughts about his future. He was hardly alone.

In 2020, 116 police officers committed suicide. In 2021, the number rose to 150. Badge of Life, an organization specializing in preventing law enforcement suicides, conservatively estimates that 150,000 officers suffer from PTSD.

“We found that around 65 percent of police officers will have PTSD,” says its website. “Out of these individuals, only 39 percent will receive treatment for their disorder. One police academy director estimates that about 15 percent of any police department’s officers are in a burnout phase at any one time, and that 5 to 7 percent are ‘crispy critters’ who are totally burned out.”

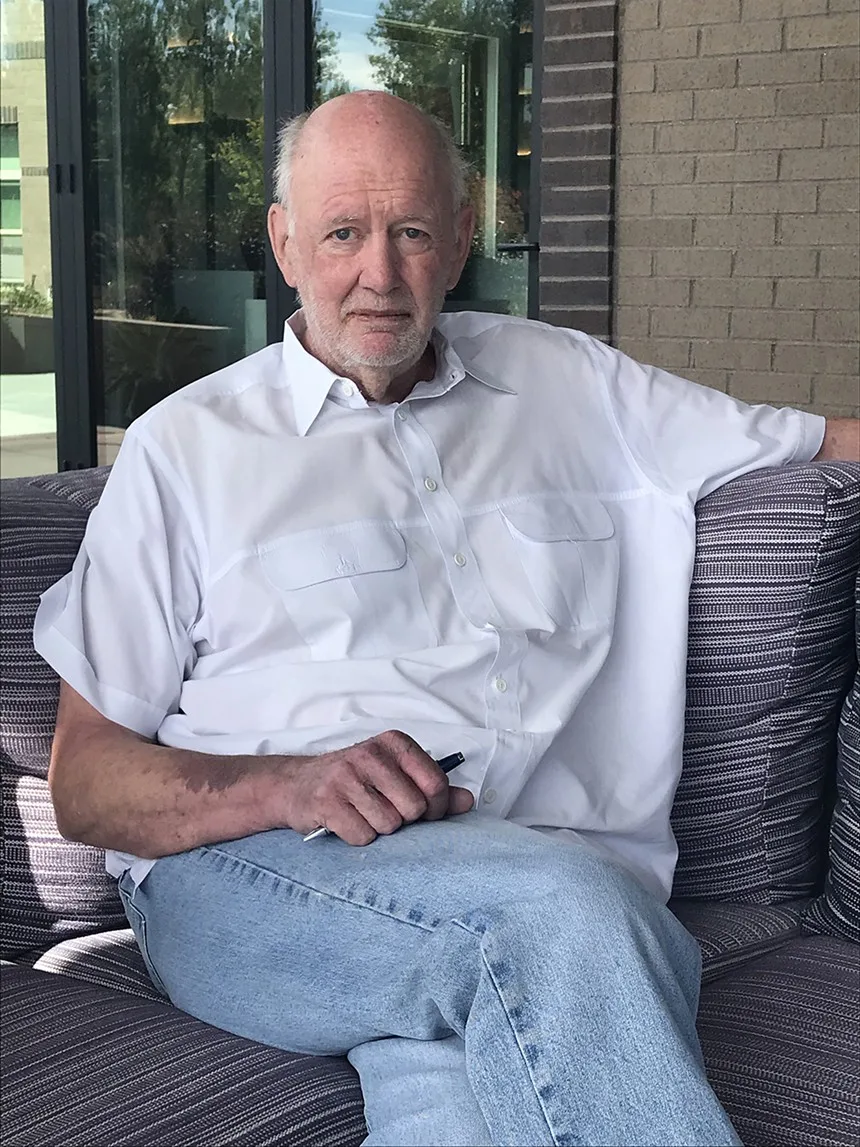

Ellis Armistead shares stories from his long career in law enforcement and private investigation.

Joyce Singular

The thirty years that Armistead has been a private investigator parallel the explosion of interest in true crime, with a glut of books, documentaries, films, podcasts, radio and TV programs, and limited series. The subject has consumed a wide chunk of the Internet with chat rooms, forums, investigative teams and countless amateur sleuths, producing good results and bad: a number of solved cold cases and some fanatical behavior around certain high-profile murders. Every day, one sees heartbreaking posts on Facebook about someone searching for a missing relative or seeking justice for a long-ago homicide.

Real people, of course, live behind these tragedies, suffering mostly in silence after events they’ll never recover from.

Armistead has been with them when the heat from the police and the media was most intense, and the impact of this has left its mark on him. They say that once a man has been in prison, he never loses the tension in his shoulders, always aware that someone may be sneaking up behind him to cause harm. With Armistead, the stress is locked into his features. His blue eyes are wide open, as if he’s just seen something he shouldn’t have. His pupils constantly move side to side, wary, the prelude to a wince. When he becomes self-conscious, his reddish face turns crimson. If you ask him to spill a few secrets about his work or to talk about his accomplishments, the relentlessly modest investigator shrugs and says, “Well, it’s really not like that.” In the middle of a painful story, his voice catches and you wonder if he might break down. His presence is haunting — not just when you’re with him, but for hours afterward. He carries with him the weight of his experience.

Over decades of writing true crime books, I’ve met countless attorneys, police officers, criminals, victims and their families, private investigators, media members and courtroom personnel. All of them, including reporters who’ve covered numerous murder trials or the atrocities of war or terrorism, deal with residual trauma. Some finally decide they can’t witness the results of any more violence and move on to other assignments. Everyone within the legal system is assigned a role that they dutifully play. Almost no one tells you what they really think or feel about a particular case. Most P.I.s have poker faces, revealing nothing while squeezing you for any scrap of information they might find useful. Even if they want to talk, they’ve often signed non-disclosure agreements preventing them from opening up about their work or violating the attorney-client privilege that lawyers have with defendants. Because of these barriers and others, the people you meet when writing true crime inevitably end up as characters in a story, no matter how hard you try to penetrate their facade. You always want to know more about them than you do, more than you can.

In the spring of 2023, Armistead, whom I’d met in the late 1990s when he was employed by the attorneys for John and Patsy Ramsey following the death of their daughter, JonBenét, reached out to me. This had never happened before with a private investigator: You have to seek them out, and then they probably still won’t talk. During our phone conversation, Armistead didn’t say much, and his purpose in calling seemed vague. He might be willing to speak about his experiences, but he wasn’t quite sure, and there were things he couldn’t get into, and…

Our discussion didn’t go anywhere, but I never stopped thinking about him. Five months passed, and I decided to dial his number to see if he wanted to get together. He was noncommittal, saying he’d think about it. Three days later, I sent an email asking if he’d like to get a cup of coffee. Fifty years into his career, he was ready to talk.

Ellis Armistead was born on the Fourth of July 1950 in Nashville, Tennessee. His father was a NASA engineer and his mother the director of nursing at a local hospital. His family moved to California for two years for his dad’s job before settling in Decatur, a city of roughly 50,000 in northern Alabama. Around age twelve, Ellis entered an awkward stage. He had a growth spurt, shooting up three inches in a year (he’s six feet seven), and was uncoordinated. Students made fun of him, and his basketball coach said that he was “too lazy to raise a fishing pole.” After a few scrapes at school, he shoved a teacher, and his father sent him to Marion Military Institute for a year, where he learned to study and control his temper.

One day his dad drove him to a Decatur sporting goods store/pawn shop and asked the owner to take on his son, with no pay, so he could get some work experience (the owner felt so guilty that he paid him under the table). Ellis’s upper-middle-class background had insulated him from those who came into the shop: the poor, the needy, drunks and dopers, drifters, grifters, and gun-loving citizens. He liked dealing with them, liked their rawness and their stories. He sold a lot of the $14.95, .22-caliber pistols known as “Saturday Night Specials” and a lot of gunpowder that customers fed to their canines to make them more aggressive during dogfights. A co-worker with a side hustle in cock fighting wanted to go into business with Ellis, giving him some magazines to take home and study. The venture lasted until his mother found them in his bedroom.

His father had his future all planned out: college at Vanderbilt, where his parents had gone, and then into banking or law. He did well at Vanderbilt and well enough on the LSAT to get into law school, but there was a problem: Ellis found both banking and lawyering boring. After graduation, he tried selling insurance – for a week — before gravitating back to the pawn shop. Cops frequented the store and told him to apply for a job with the Decatur Police Department: It was exciting to be an authority figure, to ride a motorcycle, to carry a firearm, and to learn the local ways of law enforcement. He was soon hired, and his fellow officers initiated him in the station’s DUI room by making him drink a cup of moonshine whiskey.

The next morning when he reported for duty, the chief handed him a badge and said, “Now you’re an official sonofabitch!” His annual salary was $6,000, and his parents were mortified by his choice of employment. His superiors quickly discovered that he was a “terrible shot” on the firing range, and they almost suspended him (he had his partner take target practice for him and turned in the results as if they were his own). The job was many things, but not boring. He dealt with bootleggers, dogs attacking him when he knocked on doors, and citizens enraged with the police. His towering height caused some shorter men to challenge him to fight, but he always tried to duck the “ankle biters.” When he came upon husbands and wives who were drunk and quarreling, he “divorced” them to calm them down, a trick he’d picked up watching The Andy Griffith Show.

Racial issues were ever-present. If there was a late-night shooting and the victim was Black, the police often wouldn’t go to the scene until the next day. When a dispatcher alerted patrol officers that a car full of African Americans was approaching, he’d say that “a load of coal is coming your way.” Working a local football game, Armistead got ensnared in a race riot and was pelted with rocks and other hand-launched missiles.

All that was minor compared to the murders and suicides he witnessed. At 23, he was getting inured to the smell of death. “I was not prepared for the violence I was exposed to,” he says.

A call came in about a traffic accident, and he was the first officer on the scene, where a boy had been run over by a truck. Dismounting from his motorcycle, he walked up to the body laid out in the middle of the road, covered by a sheet. In the distance, he could hear people moaning. Removing the sheet, he saw only a torso. Onlookers had gathered and were all pointing or nodding in the same direction, about fifty yards away. Following their lead, he found the boy’s head and realized that the moaning was coming from the victim’s mother and father. He asked for backup.

After finishing work that day, he drove to his parents’ home to tell them what had happened. They didn’t want to hear about it, so he went to a steakhouse, poking at his food and thinking about what he’d just seen, telling himself that it was just part of the job and he shouldn’t let it bother him. He could deal with it, tuck it away somewhere and move on.

“I was pretty good at pushing things aside,” he recalls, “because I had a strong stomach and didn’t get flustered.”

“You’re doing your work and getting things done, but you don’t see what’s happening to you personally.”

He never spoke with anyone in any depth — inside or outside of law enforcement — about this experience.

“If anyone asked me about it,” he says, “I gave them the short, sanitized version. I took pride in my ability to handle anything that came down the pike and then go home and sleep well that night.”

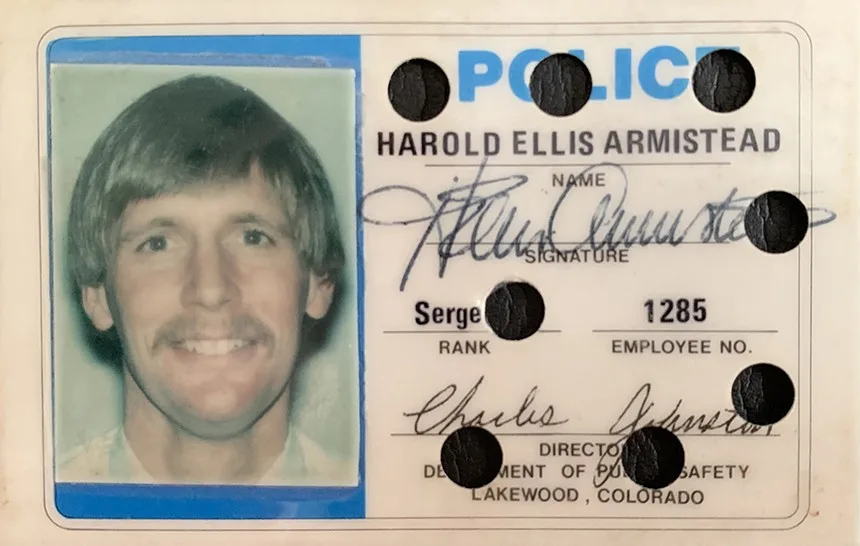

After a few years with the Decatur department, he transferred his police skills to Lakewood, Colorado. The first day he reported for work, the desk officer, knowing that Armistead came from Alabama, greeted him with, “Where’s your white sheet?” — implying that he was in the Ku Klux Klan. Starting off in patrol, he again saw a lot of suicides (a man shot himself in front of Armistead) while using police resources to earn a master’s degree in public administration/criminal justice. He was quickly promoted to homicide, and his first case involved Ron Lyle, the boxer who’d lost a world heavyweight championship fight against Muhammad Ali. Lyle was accused of gunning down a man in his home, but was acquitted after his attorney claimed self-defense.

Armistead was shot at twice — on the street near Sheridan Boulevard, and at Wadsworth and Hampden, when he was wearing civilian clothes on his way to the dry cleaners. Driving past a bank, he noticed unusual activity and stopped. As he entered the business, a robbery was unfolding, so he pretended to be a customer and joined the others in the teller line. The robber took the bank manager outside at gunpoint and Armistead pursued, drawing his weapon and blowing out the man’s car windows in an exchange of fire. Backup arrived, the offender was arrested, and Armistead was asked to retrace his steps during the gunfight. He couldn’t, because stress had erased his memory of the events. Other officers told him that similar things had happened to them. He went back to work and appeared to be unaffected.

“It takes a lot,” he likes to say, “to get me excited.”

But as he neared forty, his nightmares intensified; he was losing sleep, slipping into depression and taking Prozac, the first of many meds he’d consume to alleviate his condition. Not much changed, even after he left his job in Lakewood.

Hired as a criminal investigator in Colorado’s 14th Judicial District, he covered a large section of the state’s northwest. He relocated to Steamboat Springs, but the flashbacks, anxiety and nightmares continued, scaring both him and his wife. He was losing rest and significant weight. One of his cases involved a mother, father and their eighteen-month-old son, who’d all been shot in the back of the head and left in a ditch. In the morgue, Armistead held the child in his arms and promised himself that now, finally, he’d get away from the criminal justice system. But he didn’t leave his job.

Badly in need of a respite, the Armisteads and another couple took a two-month trip to Nepal and Thailand. They had no itinerary, just got off the plane and began trekking across the two countries, hiking and absorbing the beauty of the landscapes and jungles, sleeping on dirt floors and interacting with the local population. For the first time in years, Armistead let down. The people in Nepal had so little, but seemed happier than those in America who had so much. Filling each day with exploration and physical exertion, he enjoyed what he later called “the most peaceful time in my life.”

Back in Steamboat Springs, he had to listen to the full confession, including many grisly details, as the triple-homicide killer laid out his crime. Armistead’s depression and panic attacks resumed. He quit his job and became a process server in Steamboat until word of his career switch reached Denver, where prominent defense attorneys sought him out to be their private investigator on criminal cases. He resettled in the Mile High City and crossed over, as some in law enforcement put it, to “the dark side” – now representing those accused of serious offenses. One detective nastily asked him how he could live with himself.

“I thought we were friends,” Armistead says.

As a P.I., he clearly defined his role: He was an investigator, not an advocate for the clients. His job was to uncover bad evidence and bad alibis and pass them along to the lawyers so they wouldn’t get ambushed in court by something they didn’t know. Seventy percent of what he dug up fell into this category. He was good at digging, at being discreet, at getting people to talk to him, and at staying calm and neutral in all kinds of difficult situations.

He’d never again carry a gun, but he couldn’t escape violent crime. His first P.I. case came when a young man shot and killed a state trooper near Idaho Springs, particularly difficult since Armistead had spent the past seventeen years in law enforcement.

His career presented a quandary. He liked using his intelligence to investigate, liked the action around the criminal justice system and learning things not everyone knew: which police officer was jumping out of which reporter’s bedroom window at midnight; how attorneys hid microphones in their briefcases to make secret recordings of their adversaries; and what cops did to unwind on road trips – starting with a whole lot of beer. But the depression and nightmares continued, along with his consumption of meds.

“I think I’ve taken everything available for anxiety,” he says.

He didn’t want to stop being an investigator, but didn’t know how to combat the toll it was taking.

“There’s an adrenaline rush that comes when you get involved in murder cases, especially if they’re high-profile,” says Greta Lindecrantz, a Denver P.I. who’s worked with Armistead on several occasions and been involved in nineteen death penalty cases. “But there’s also a need for sensitivity. That helps you do the job, but it also makes you vulnerable. You’re dealing with the loss of a human being and the loss of a member of a community. You have to be sensitive to that, while also trying to gain the trust of your clients. They may be mentally ill, and you try to discover what led them to this moment.

“Ellis is very good at doing all of these things and at being intuitive, but this opens him up to that sensitivity and vulnerability,” she continues. “You absorb everything from these experiences. Everything you see, hear and smell, your body remembers and stores. I can recall when the smell of blood was so strong at a crime scene that I had to get away and couldn’t tell anyone what I was experiencing. A lot of dark humor surrounds this work as a coping mechanism, but it’s not healthy. People pay a price for this with heart attacks or cancer or drinking too much.”

One night after going to a bar with Armistead, Lindecrantz followed him home in her car, worried he wouldn’t make it there safely. Another night he called a well-known Denver TV reporter to come pick him up at a tavern and then slept at his residence. When not working or heading out for a drink, he jogged alone during the week to decompress, and on weekends ran eight to ten miles with others. It was good for his physical health, but it didn’t stop the nightmares or panic attacks.

In 1980, PTSD had been officially proposed as an anxiety disorder. A decade later, Armistead was diagnosed with the condition and began seeing a psychiatrist, a relationship that would last for the next 22 years, until she retired. Then, after a false start or two, he found another one. He was trying hard to cope with his job and to be proactive with his mental health.

“When you observed Ellis, you could see and feel his humanity, and that made it easier to show your own vulnerability and humanity,” says Lindecrantz. “He treated me with great respect, was very collaborative, and listened to what I had to say. That isn’t true of every male private investigator I’ve worked with. Some of them didn’t want to hear my opinions. Away from work, Ellis could do all the ‘old boy’ things, but on the job he treated women very well. At one point he had about a dozen employees, and all of them were women.”

Elllis Armistead’s jobs as a P.I. included working with the Ramsey family at their Boulder home.

Getty Images/Michael Smith

As the 1990s unfolded, a new reality added to the pressure and stress, bringing the media and public into the criminal justice system as never before. The Internet was now in play, and the true crime phenomenon was exploding. Everyone was under more scrutiny as Colorado became the epicenter of three crimes that made national headlines.

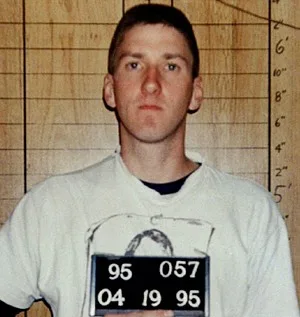

Armistead’s initial death penalty case didn’t quite reach that level. In 1993, nineteen-year-old Nathan Dunlap killed four people at a Chuck E. Cheese restaurant in Aurora. When Armistead met the young man in the county jail for his first legal advisement, Dunlap had covered himself with his own feces; the investigator had to cover his nose to endure the smell. Dunlap was “out of control,” and the P.I. felt an instant dislike, if not revulsion, for him. His work on the case didn’t impact just him, but also his wife.

“Why,” she pointedly asked him one day, “am I ironing Nathan Dunlap’s clothes?”

Over time, Armistead’s view of the prisoner began to change. With the help of the corrections system, Dunlap attempted to rehabilitate himself and now mentors other inmates. He calls Armistead every year on his birthday and Thanksgiving.

“When the case started,” Armistead says, “I didn’t understand as much about mental illness as I do today. You can’t put rational thinking onto irrational acts. Nathan has become an example of someone who can make his own life in prison and be productive. Most people aren’t beyond redemption, if given the right support.”

“I didn’t understand as much about mental illness as I do today. You can’t put rational thinking onto irrational acts.”

In 2020, after Colorado voted to abolish the death penalty, Governor Jared Polis commuted Dunlap’s death sentence to life in prison without parole.

Armistead’s reputation as an investigator was growing, and he drew in famous clients, including Aspen’s Hunter Thompson. After getting into a bar fight, Dr. Gonzo contacted him seeking legal help. He began ringing him up in the middle of the night, complaining about his situation and causing the P.I. to back away.

Armistead’s feelings about the late author are terse: “He was an idiot.”

In late 1996, Armistead and those in his running group caught a news bulletin — something about the six-year-old daughter of a wealthy businessman found dead in the basement of their Boulder home. “That one won’t take long to solve,” Armistead casually remarked to the others.

After John and Patsy Ramsey returned to Colorado following their infamous January 1, 1997, CNN interview about the murder of JonBenét, Armistead’s phone rang. The prestigious Denver law firm of Haddon, Morgan and Foreman tapped him to be the Ramseys’ private investigator. He was soon driving the family around town as they scurried from one place to another to avoid the media, especially the tabloid reporters who’d descended on Boulder and were conducting round-the-clock surveillance on the parents, swinging from trees onto the roof of their house at night to look for clues. When Armistead suggested to his wife that they let the Ramseys stay with them for a while, the idea met with strong resistance.

With the Ramseys trapped in the frenzy, the P.I. made a point of getting JonBenét’s brother, nine-year-old Burke, away from the action, taking him outside to play in the street with his electric cars. Before long, a “tabloid clown” came after the investigator himself, breaking into his bank account and offering his younger brother, Steve, $50,000 to deliver dirt on his sibling. Nothing came of this, except Armistead’s anger.

“If it had been me,” he says, “I’d have taken the money and just made something up for them.”

When the Ramseys publicly declared they had the best investigative minds in the business working to solve the murder, Armistead and his staff were bemused. The case was turning out to be far more baffling than the P.I. — and countless others — had first imagined. At the height of the Ramsey hysteria, when “the crazies” began showing up at Armistead’s office unannounced with theories about the killer, he installed a stick-up alarm system (designed to stop burglars) that sent an alert to the police. He’d testify before the Ramsey grand jury, but after three years he quit the case because he didn’t like the leaks to the media or the dynamics between the district attorney, the press and the defense team. He was particularly annoyed that the aging Bill McReynolds, who’d played Santa Claus for the Ramseys at their Christmas parties, had died with accusations of murdering the child hanging over him.

“That stigma,” Armistead says, “never leaves you.”

More than a quarter-century after the crime, no one has been arrested for it, and Armistead retains cabinets full of leads on the homicide. Every year, a handful of women call him to say that their ex-husbands are good for the murder and should be taken into custody. He remains tight-lipped about the girl’s death, but allows that the “intruder theory” — of someone coming into the Ramsey house that night and carrying out the murder in a wine cellar in the basement — doesn’t hold up.

“The first time I was in the Ramseys’ home,” he says, “it took me ten minutes of walking around just to find the wine cellar. You’d have to be very familiar with the layout of the house to know where that is.”

Like Armistead, Greta Lindercrantz has also worked numerous high-profile cases — and paid for it. “Death threats, intimidation, being chased — it all comes with the job now,” she says. “I was pinned up against a wall by a reporter, and I started hitting and kicking back. I hit his camera, and he said, ‘Don’t ever touch my camera.’ I’ve had people waiting for me in my driveway when I got home. It was terrifying. I also have PTSD.

“What Ellis and I have gone through,” she continues, “is common in our profession. People go along and do their jobs, and then they snap and can’t do it anymore. It’s a failure to recognize what’s happening to you on a daily basis. You’re doing your work and getting things done, but you don’t see what’s happening to you personally.”

“You’re doing your work and getting things done, but you don’t see what’s happening to you personally.”

On April 20, 1999, Armistead was in California speaking with a suspect in a triple homicide. Leaving the jail, he checked his pager, now completely full of messages. He called his office and was told to return to Denver immediately. His staff had been contacted by a lawyer and ordered to go pick up the parents of Eric Harris, one of the shooters in the massacre inside Columbine High School that day. It wasn’t yet clear if Harris and the other shooter, Dylan Klebold, were dead or alive. Armistead’s employees phoned law enforcement and learned they were deceased. His staff members drove Katherine and Wayne Harris to the Warwick Hotel in downtown Denver, checked them in under Armistead’s name, and waited for him to arrive. When he walked into the room, Katherine Harris was curled into a fetal position and sobbing. Wayne Harris came up to the investigator and said, “Just flush him!”

Armistead’s job was to keep the couple secure for the next few weeks, as they moved into and out of a series of hotels. During that time, he watched as “some of the nicest people I’ve ever met” tried to accept the horror of what their son had done.

“The father and mother,” he says, “were collateral damage in Eric’s crime. I don’t think people understand what that really means and how many others are affected by major crimes: families, victims, first responders, judges, juries, law enforcement, witnesses, lawyers and private investigators. After things began to settle down, the parents went back and lived in their home. The neighbors made a point of running off the press so they’d be left alone. I thought that was commendable.”

Some years after Columbine, a Phoenix attorney called Armistead following a mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, leaving 23 dead and 22 wounded. The lawyer wanted him to join the defense team, but he’d learned to say no.

“I’d just finished a prison gang case,” he says, “and I told the man, ‘I don’t want this case, and you shouldn’t, either. If you take it, your wife will kill you if I don’t do that first.’”

In 2001, when he was transporting Timothy McVeigh’s ashes, Armistead’s psychiatrist called just to ask how he was doing.

“It was very comforting to hear her voice,” he says. “At the time I thought I felt fine, but maybe I was dulled out and didn’t feel anything.”

In 2004, his marriage ended. In 2005, in a downward spiral, he reached out to his sister, Ellen, in Seattle. He’d been diagnosed with Treatment Resistant Depression and the panic attacks had returned. With help from his family, he entered a Nashville facility and was put in group therapy, where he was expected to “spill my guts about my problems.” He couldn’t do this, because non-disclosure agreements prevented him from speaking openly about his criminal cases. He left the group and for thirty days went one-on-one with a resident psychiatrist, opening up about his condition.

“I didn’t feel I was good enough,” he says of that period, “even though people were telling me I was good. Some days I didn’t think I was human because I wasn’t feeling things. The thirty days didn’t help me.”

He went back to work, but the anxiety continued. In 2013, he was having night sweats, traveling constantly, and drove out of an airport terminal and rear-ended a car. He’d soon be diagnosed with stage 4 non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which can be fatal, and spent six months in a Nashville hospital. Away from Denver and his office, he was finally able, as he’d done more than two decades earlier in the Far East, to let down and find some peace.

Finishing up the rigors and aftereffects of chemotherapy, he went back to work. In 2016, he was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Professional Private Investigators Association of Colorado. A year later, he started electro-shock treatments to end the nightmares and other symptoms, but “it didn’t make much difference,” he says. In 2018, he tried ketamine, but it, too, had little impact. Investigating a murder case near Pagosa Springs, he became disoriented, his GPS app failed, and he got lost on a Native American reservation.

“They attributed this to the ketamine,” he says. Driving around the reservation, his car slid off an icy road, and a police officer came by and pulled him out. When he returned to Denver, his staff confronted him, saying that he shouldn’t keep working and threatening to resign. Ellen and his brother, Steve, flew in to meet with the employees and assure them that their brother was all right. The next day, with the exception of one person, the entire staff quit.

“I was numb,” Armistead says of the exodus.

He continued going to the office full-time and took on numerous fentanyl cases as the drug made its way up from Mexico to Denver, along with the occasional murder. The longer he’d been a P.I., the more he’d noted several disturbing trends: Offenders had steadily gotten younger; semi-automatic weapons were much easier now for individuals to convert to fully automatic, making them even more lethal; and the adversarial system in the courts was growing more adversarial, echoing the state of American politics.

He recently got a case in which a 22-year-old woman was shot between the eyes with a hollow-point bullet.

“When I look at crime scenes or autopsy photos on a computer screen now,” he says, “I can smell the blood. I don’t have to be there to do that.”

In early fall, once Armistead decided to open up and reflect on his career, the more committed he became to sharing his story with the public.

“The worst moment for me came when facing the reality of the damage my work had done to me personally and the collateral damage it had done to others around me — my family and my employees,” he says. “The best moment is that I’ve had probably fifty people work for me, and I’m very proud of what they’ve done. They’re my legacy. I’ve given them technical knowledge, but also tried to instill values. I always warned them about setting boundaries — not getting emotionally involved with their cases.

“My goal in speaking out about my PTSD is that there are hundreds and thousands of people just like me,” he continues. “Many have been through experiences similar to mine, and some have had it much worse. People in the system need to recognize that they’re impacted by this kind of work. I’ve received some notoriety because of the cases I’ve done, but my work is not the totality of me. That has more to do with being able to see good come out of terrible situations. I look past the gruesomeness — the physical parts of these events – and look for the positive things. I’ve seen people become stronger out of tragedy.

“I’m proud of what I’ve done and don’t have regrets. I just wish I could have been happier and had a better attitude. I still feel depressed. I wake up in the morning and have to push myself to get going, but none of this was forced on me, and I’ve enjoyed the work and still do. Two of my death row clients were executed, but I don’t quit because of that. I have a job to do.”