Harpers Ferry seemed almost a part of the neighborhood when I was growing up. Granted, it was across the state line, in West Virginia, and slightly more than a half-hour drive away from our Virginia farm. But it took us almost that long to get to the nearest supermarket. And I felt connected by more than roads. The placid, slow-moving Shenandoah River, which flowed past our bottom pasture, becomes raging white water by the time it joins the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry, 35 miles downstream.

Nature itself seems to have designed Harpers Ferry to be a violent place. Cliffs border the confluence of the two rivers, and the raw power generated by their angry convergence made the site ideal for the national armory established there around 1800. It manufactured some 600,000 firearms before Union troops burned it down in 1861 to keep it out of Confederate hands. Five battles took place at Harpers Ferry, and the town changed hands 12 times.

But none of this is what Harpers Ferry is primarily remembered for. It is known instead for an event referred to at the time as an “insurrection,” a “rebellion,” or a “crusade,” but today most often called just a “raid.” On October 16, 1859, a year and a half before the attack on Fort Sumter, in South Carolina, the white abolitionist John Brown set out to seize the federal arsenal and distribute arms to enable the enslaved to claim their freedom. His effort ended quickly and ignominiously. Badly wounded, he was carted off to jail in nearby Charles Town to be tried and executed, as were a number of his followers. In a sense, though, his insurrection was never put down.

Brown, a brilliant publicist, made himself a martyr. He used the six weeks between his capture and his execution to define and defend his actions. He grounded them in a moral imperative to free the enslaved, invoked the nation’s revolutionary legacies, and warned of the conflagration to come. The “crimes of this guilty land,” he scrawled in a note he pressed on a guard shortly before his hanging, “will never be purged away; but with Blood.”

Within just a few years, Americans would look back at Brown across the gulf of the Civil War and identify him as a sign of what was ahead, imbuing his sacrifice with almost supernatural meaning. Showers of meteors had filled the skies in the weeks between Brown’s capture and his execution, reinforcing perceptions that his life and death had been a singular, numinous occurrence. In the words of a song improvised by a battalion of Union soldiers as they headed south to war not two years after his death, “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave, but his soul goes marching on.” Even the attendees at his hanging seemed in retrospect to prefigure the future: Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee was present as the commander of the U.S. troops who had captured Brown. Thomas J. (not yet “Stonewall”) Jackson led a unit of Virginia Military Institute cadets. John Wilkes Booth, President Abraham Lincoln’s future assassin, hurried from Richmond to Charles Town in a borrowed uniform to join a militia troop sent to police the hanging. He hated Brown’s cause but admired his audacity.

Many upstanding northern citizens—as well as much of the press—condemned Brown’s lawlessness. But others, Black and white, hailed his attack on slavery and mourned his death. On the day of his execution, 3,000 people gathered in Worcester, Massachusetts, to honor Brown; 1,400 attended a service in Cleveland. A gathering of Black Americans in Detroit honored the “martyr” who had “freely delivered up his life for the liberty of our race in this country.” The celebration of John Brown by Black Americans rested in the hope, and later the conviction, that his actions had set an irreversible course toward freedom—a second founding, its birth in violence as legitimate as the first one had been.

When does war start? When does violence become justified? When does it shift from prohibited to permitted and even necessary? Those questions hang in the air at Harpers Ferry, compelling us to ask: When did the Civil War actually begin—and end?

Brown drew the admiring attention of almost every prominent American writer—Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman, Melville, Longfellow, Whittier. But some among the nation’s northern elite did more than praise and defend Brown. Thinking back in his autobiography to events half a century earlier, and relying on a diary he kept in the 1850s, the abolitionist and writer Thomas Wentworth Higginson reflected on what a duty to morality demands when “law and order” stand on “the wrong side” of right and justice.

For him, this was not a theoretical question. He was thinking about the role he’d played long before armies massed on battlefields. He was thinking about the process by which “honest American men” had evolved into “conscientious law-breakers,” until “good citizenship” became a “sin” and bad citizenship a “duty.” Higginson was one among a small group of prominent white men who had known about the Harpers Ferry raid in advance and provided the financial support that enabled Brown to buy weapons and equipment. They came to be known as the Secret Six.

During the 1850s, a succession of legislative and judicial measures had tightened slavery’s grip on the nation. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 compelled the North to become complicit in returning those who had escaped slavery to southern bondage. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 overturned the Missouri Compromise of a generation earlier, which had restricted the expansion of slavery into the northern territories. The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, in 1857, established that no Black person could be considered a citizen or hold any “rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The perpetuation of slavery and racial injustice appeared to have become enshrined as an enduring national commitment, with the federal government assuming the role of active enforcer. Faced with such developments, the Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass found himself losing hope of ending slavery through moral suasion or political action; he came to see violence as necessary if emancipation was ever to be accomplished. Slavery itself, he believed, represented an act of war. The justification for violence already existed; whether—and how—to use it became more a pragmatic decision than a moral one.

White abolitionists, too, became radicalized by the developments of the 1850s. The group that became the Secret Six included five Boston Brahmins and a lone New Yorker, all highly respectable citizens, well educated, of good families and heritage; all men of means and in several cases very substantial means. The path that the Six took toward violence began with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act. The prospect and, soon, the reality of Black people being apprehended on the streets of Boston or New York and summarily shipped to the South brought the cruelty and arbitrariness of slavery directly before northerners’ eyes. Three men who would later be part of the Six were early members of the Boston Vigilance Committee, established to prevent the enforcement of fugitive-slave legislation.

Samuel Gridley Howe was a graduate of Brown University and Harvard Medical School. He claimed descent from a participant in the Boston Tea Party, and had demonstrated his commitment to republican government by serving as a surgeon in the Greek Revolution in the 1820s.

Theodore Parker was a powerful preacher and Transcendentalist whose radicalism so marginalized him within Unitarianism that he established his own independent congregation of some 2,000 members. His oratory attracted legions of followers, who shared his reformist and antislavery views.

Higginson, descended from one of the original settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, was a graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Divinity School and held a pulpit with a fervently antislavery Worcester congregation. He suffered his first battle wound in the unsuccessful effort to free Anthony Burns, who had fled enslavement in Virginia and was seized in Boston in 1854 under the provisions of the new act. With the encouragement of the Boston Vigilance Committee, the city erupted. Parker incited a crowd with a fiery speech at Faneuil Hall, and Higginson distributed axes to those assembled outside the courthouse where Burns was being held. He himself led an assault on the building with a battering ram. In the ensuing melee, a courthouse guard was killed and Higginson suffered a saber wound on his chin, leaving a scar he proudly displayed for the rest of his life. Higginson viewed the effort to free Burns as the beginning of a “revolution”—the shift from words to action he had sought. The killing of the guard, he later reflected, was “proof that war had really begun.” Violence had become both necessary and legitimate. (Burns was captured and returned to Virginia, but his freedom was eventually purchased by northern abolitionists. He attended Oberlin and became a minister.)

Higginson, Parker, and Howe soon turned their attention to Kansas, where a battle was escalating over whether the territory should become a slave state or a free state. In the spring of 1856, proslavery forces attacked a town founded by antislavery settlers from Massachusetts. John Brown, a longtime opponent of slavery who had joined his sons in Kansas with the intention of preventing its permanent establishment there, sought retribution; he and his allies killed five proslavery men in front of their families in a place called Pottawatomie. This murderous act hovered over Brown’s reputation—and later his legacy—instilling doubts in some potential supporters and leading others simply to deny that Brown had played a role in the killings, a stance that was aided by Brown’s own misrepresentations.

But to many, Brown’s extremism was a source of attraction, not revulsion. The newly created Massachusetts State Kansas Aid Committee channeled outside support. Higginson sent crates of rifles, revolvers, knives, and ammunition, as well as a cannon, to Kansas. He celebrated Kansas as the equivalent of Bunker Hill—a “rehearsal,” he later called it, for the more extensive violence to come.

It was because of Kansas that the six men who would conspire to support the Harpers Ferry raid found one another and identified Brown as the instrument of what they had come to regard as necessary violence. Like Parker, Higginson, and Howe, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn and George Luther Stearns had become active supporters of the Massachusetts State Kansas Aid Committee. A Harvard graduate who was a schoolteacher in Concord, Sanborn had been deeply influenced by Parker’s preaching while he was in college. Sanborn’s Transcendentalist ideas, with their skepticism about existing social structures and institutions, were further reinforced by his Concord neighbors Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Stearns was a wealthy manufacturer whose ancestors included some of the original settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony as well as an officer in the American Revolution. Long active in abolition, he had established a station of the Underground Railroad near his Medford home and drew on his considerable fortune to send weapons to Kansas free-state settlers.

The last of the Six was Gerrit Smith, said to be the wealthiest man in New York State. Smith, like Stearns, would supply significant financial support to Brown. He had long been active in politics, seeking the destruction of slavery through political means, but by 1856 he had come to believe that it was time, as he put it, to move beyond ballots and start “looking to bayonets.” Parker, too, was preaching more forceful measures. “I used to think this terrible question of freedom or slavery in America would be settled without bloodshed,” he wrote to Higginson. “I believe it no longer.”

By the end of 1856, under the leadership of a commanding new territorial governor, violence in Kansas had begun to subside, and a free-state electoral victory seemed all but assured. The following year, Brown began traveling throughout New England and New York to raise money for a fresh attack on human bondage—his new plan as yet unspecified. In Boston, he presented Sanborn with a letter of introduction from Smith. Sanborn in turn arranged for Stearns, Howe, and Parker to meet Brown. Uncertain what Brown intended, Higginson at first kept his distance, even though Sanborn pressed him, insisting that Brown could do “more to split the Union than any man alive.” The ideals of the once noble American experiment could be sustained only by separating from slavery or by destroying it.

In February 1858, Brown revealed his plan for the Harpers Ferry attack to Smith and Sanborn. Not long after, all of the Massachusetts conspirators met with Brown in his Boston hotel room and formally constituted themselves as the Secret Committee of Six to support Brown in planning and financing the raid. Stearns was to be the official chair, Sanborn the secretary. They would keep careful records, with an elaborate ledger and a dues schedule. It was as if a clandestine organization of accountants had set to planning an uprising.

The raid’s actual occurrence surprised them—with both its timing and its swift and disastrous outcome. On October 16, 1859, Brown and a party of 21 seized the federal arsenal, eventually taking several dozen hostages. The uprising of the enslaved that Brown expected never materialized, and local militia soon cut off the bridges that were the only escape route. Brown and his men blockaded themselves in the armory’s fire-engine house, where they exchanged intermittent gunfire with the troops surrounding them. On October 18, Colonel Lee and a regiment of U.S. Marines broke down the engine-house door. Wounded by a saber cut, Brown was taken prisoner and transported to the nearby Charles Town jail. Ten of Brown’s men, including two of his sons, were killed; seven, including Brown, were captured and later executed. Four civilians were killed, as was one Marine. To the great dismay of the Secret Six, Brown’s papers and correspondence were found at the farm where Brown had been living in Maryland.

The Six were stunned. In the press and in government offices, accusations flew. Many suspected that Frederick Douglass must have played a role. More than a decade before the raid, Douglass had met Brown and been moved by their conversations to question his own belief in the possibility of a peaceful end to slavery. “My utterances,” he later wrote, “became more and more tinged by the color of this man’s strong impressions.” When Brown took up arms in Kansas, Douglass’s appreciation for his boldness and conviction was only enhanced. Yet Douglass proved unwilling to join Brown when he revealed his Harpers Ferry plans. The scheme struck him as dangerously impractical and risky—“a steel-trap.”

In the aftermath of the raid, Douglass seemed almost embarrassed that he had not offered Brown more support, that he had permitted realism to trump daring. He could not conceal his admiration for the would-be liberator’s courage, but concerns for his own survival won the day. Douglass fled north to Canada and then to England, where he remained for nearly half a year.

Although Douglass was all too aware of his vulnerability, the Six, protected by their social position, had been defying authority with seeming impunity for years. Their recognition of personal peril came as a shock. The Six had embraced violence out of both entitlement and desperation. In public and private communications, they frequently invoked their revolutionary heritage, their biological connections to the country’s Founders—to those who had pitched tea into Boston Harbor and fought at Lexington and Bunker Hill. This was a legacy—and a responsibility—that required them to act with equivalent courage and decisiveness. They believed that in some sense, they owned the nation, and their sense of privilege fueled a confident assumption of immunity from serious consequence. But with Harpers Ferry, it seemed, they might have gone a step too far.

Letters from Smith, Stearns, Howe, and Sanborn were found among Brown’s papers and featured in the press before the end of October. Five of the Six were quickly exposed and excoriated. (Parker, who had left the country before the raid in a futile search for a cure to his tuberculosis, was identified within a few months.) Smith fell into a frenzy of worry about being indicted. After becoming, according to his physician, “quite deranged, intellectually as well as morally,” he was committed in early November to the Utica Lunatic Asylum. After consulting a Boston lawyer, Sanborn, Stearns, and Howe made their way to Canada (and Howe published an article disavowing Brown). All three returned to the U.S., but Canada remained a refuge. Howe and Sanborn went back and forth twice. Higginson, both at the time and later, was contemptuous of his fellow conspirators’ cowardice. John Brown deserved better from them. “We of the Six,” he maintained years later, “were not—are not—great men.” But Brown, he believed, was.

Higginson neither hid nor fled. He busied himself raising money for Brown’s defense and endeavoring to devise a scheme to facilitate Brown’s escape. But even for Higginson, who seems never to have contemplated a battle or a risk he didn’t relish, these plans seemed too far-fetched. Instead, with admiration, Higginson watched Brown’s display of undaunted courage throughout his trial as he refused to plead insanity or back down in his commitment to ending slavery through whatever means necessary. Brown would do far more from the grave than he could have ever imagined accomplishing in life. Higginson spent the day of his sentencing with Brown’s wife and the remaining members of his family on their bleak and remote upstate–New York farm.

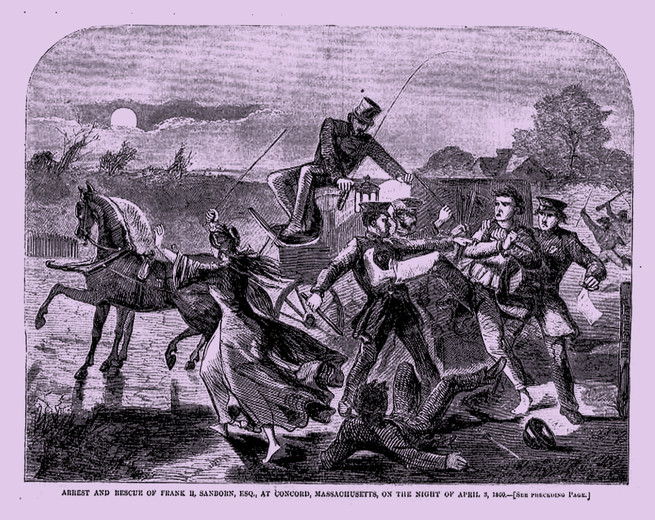

The congressional committee appointed in December to investigate the origins and supporters of Brown’s raid proved only a feeble threat to the six conspirators. Higginson, to his disappointment, was never called to testify at all. Howe and Stearns dodged, equivocated, and at times outright lied. Smith was judged too unwell to attend. Parker died in Italy in May 1860 without ever returning to the United States. Sanborn’s fears were at last realized when the U.S. Marshals he had eluded for so long arrived at his house in Concord to compel his testimony. Citizens of the town rose up to prevent his removal while a judge sympathetic to Sanborn was located to issue a writ of habeas corpus. In the end, the congressional hearings were a tepid affair, likely because southern representatives came to recognize that the less attention given to abolitionist voices, the better.

The next battle in the war that Brown had begun would not be long in coming. While he bided his time, Higginson published in February 1860 the first of a series of articles in The Atlantic that he referred to as his “Insurrection Papers.” After writing essays on “The Maroons of Jamaica” and “The Maroons of Surinam”—Black groups who had escaped enslavement to establish their own independent societies on the fringes of white settlement—he proceeded to publish admiring essays on Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, and Gabriel, men who had embraced violence in their efforts to overturn American slavery. In addition to his writing, Higginson devoted the 16 months between Brown’s execution and the firing on Fort Sumter to reading about military strategy and drills, and to practicing shooting and swordplay. In 1862, this man of words returned to the world of action. He would fulfill “the dream of a lifetime” as the colonel commanding the First South Carolina Volunteers, a regiment of the formerly enslaved. This commission embodied what he had believed in for so long: the mobilization of force in the cause of Black freedom, as well as the arming of Black men in their own liberation.

Both during and after the war, the careers of the Secret Six fell along a spectrum. Stearns never went to war himself but recruited thousands of Black troops into what he referred to as “John Brown regiments”; when the war was over, he helped found the Freedmen’s Bureau, which provided land and other assistance to newly freed African Americans. Howe worked with the Sanitary Commission, a relief agency founded to support sick and wounded soldiers, and, like Stearns, was involved with the Freedmen’s Bureau after the war. Smith emerged from the Utica asylum fragile and aversive to any conversation about Harpers Ferry. He gave a significant amount of money to Stearns’s Black regiments. And yet, in 1867, he was also among those who paid the bond that freed Jefferson Davis from prison. Sanborn appointed himself the custodian of Brown’s legacy, publishing four books and some 75 articles about him. (Many of the articles appeared in this magazine.) Sanborn cultivated the memory of a kinder, gentler Brown, downplaying the violence he had perpetrated. He did not know until the 1870s that Brown had lied to him about his central and murderous role at Pottawatomie.

Higginson was unapologetic. In 1879, when he remarried after the death of his first wife, Higginson chose Harpers Ferry as the site for their honeymoon, introducing his bride to prominent landmarks from the raid, the trial, and the hanging. Higginson never forgave himself for not doing more to support Brown and for failing to persuade him to adopt a plan that was more likely to succeed. To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the raid, in 1909, Higginson joined Sanborn, the only other surviving member of the Secret Six, and Howe’s widow, Julia, in Concord, where they were interviewed by a journalist. (Julia Ward Howe had in 1862 published on the cover of The Atlantic different lyrics for the tune of “John Brown’s Body”: the immortal words of “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”) As a writer and an activist, Higginson had remained deeply engaged in public life, notably on behalf of women’s rights; his views on race and Black suffrage tended to shift with time and circumstance, and he was far from the radical of the prewar years. But in the Concord interview, he expressed no second thoughts about his commitment to violence on behalf of abolition—either at Harpers Ferry or within the legitimating framework of the Civil War.

I learned the story of John Brown at an early age. It might have been that my father told my siblings and me about the history of Harpers Ferry as we drove along Route 340, peering down the cliffsides at the town and the rushing water below. Or Brown might have been one of those historical personages whose names we just knew, inhaled from the Virginia air around us. People like Stonewall Jackson and John Mosby and Turner Ashby, who had all likely ridden across the very fields surrounding our house. When I was growing up, I was always proud to live in a place associated with so many famous forebears. It was many years before I thought to question what their fame and vaunted heroism had been in service of.

But I knew from the outset that Brown’s renown was different. He was, I was told, a madman, undertaking a scheme that was doomed to fail—a suicide mission. When I wrote about Brown for my first term paper in high school, that was the story I told.

From 1859 onward, many observers, reporters, and, later, historians adopted the view that Brown was insane, and by the mid-20th century, when I was in school, it had become a widely held assumption among white Americans. Rather than a “meteor” anticipating or inaugurating the larger war that would end slavery, Brown became no more than an aberration. Violence was reduced to a mental-health problem. The interpretation reassuringly diminished the moral force of Brown’s actions and suggested that only madness could lead to dreams of overthrowing white dominance and Black subordination. This message was intended to emphasize the strength and immutability of the racial hierarchies that remained in place well after slavery’s end, surviving Reconstruction and enshrined in Jim Crow. It minimized the threat Brown posed and by implication all but removed him—and his insistence on the moral evil of slavery—from any place in explanations of the Civil War’s origins. The Lost Cause portrait of a conflict fought by two honorable opponents who differed primarily on constitutional views about states’ rights could remain intact and unchallenged.

Even in the days just after the raid, though, there were those who insisted on acknowledging the historic import of Harpers Ferry as well as the sanity and determination of John Brown. Governor Henry Wise of Virginia came to Harpers Ferry to interview Brown after his capture and rejected the idea that Brown was a lunatic: “They are mistaken who take him to be a madman,” he said. He left with an impression of him as “a man of clear head … cool, collected, and indomitable.” A sane Brown was far more dangerous. If his actions were rational, then the South must regard them as proof that the North was plotting the violent overthrow of slavery. The South, Wise insisted, needed to take active measures to defend itself and its way of life. One South Carolina politician described the raid as “fact coming to the aid of logic”: the South’s worst fears made real. Harpers Ferry was the moment that changed everything. The rabidly proslavery Wise and the radical abolitionist Higginson agreed on little else, but this they regarded as self-evident.

To accept slavery as the cause of the Civil War dictates setting the conflict within a longer trajectory of violence, one that starts at least with John Brown rather than Fort Sumter. Higginson would perhaps have us date the war from his saber cut in 1854. Douglass might well argue that it began in 1619. And when did the Civil War end? Historians studying the era after Appomattox have in recent years emphasized the persistence of violence through and beyond Reconstruction, as intransigent former Confederates turned from organized military force to beatings, burnings, whippings, shootings, and lynchings in the effort to suppress newly gained Black freedom. The war, the historians argue, simply continued in other forms. It is as difficult and complicated to say when the Civil War ended as to determine when it began.

In the years since 1859, John Brown and his raid have become a touchstone in America’s struggle to reconcile—or at least represent—the complex connections between force and freedom. The United States was founded in violent resistance and then guaranteed its survival as a nation eight decades later in a bloody Civil War. Violence is at the heart of our national mythology. The Secret Six drew explicitly on that mythology in their writing. It is central to our national creed. But violence has also, as Frederick Douglass reminds us, rested at the core of the social and legal order that mandated and sustained the oppression of millions of Americans from the early 17th century into our own time. Violence could enslave and violence could free. The purpose mattered. As Douglass declared, looking back on the Civil War in a Decoration Day speech honoring the Union dead in 1883, “Whatever else I may forget, I shall never forget the difference between those who fought for liberty and those who fought for slavery.”

The Black community did not forget that Brown had fought for liberty. After the war, his raid and his death continued to be commemorated across the North. In a stirring address at Storer College, founded in Harpers Ferry in 1867 to educate African Americans, Douglass insisted that Brown had not failed, but had begun the “war that ended slavery.” W. E. B. Du Bois held Brown in similarly high esteem. In 1906, the second gathering of the Niagara Movement, the predecessor of the NAACP, was held at Harpers Ferry in acknowledgment of Brown’s contributions to Black rights. Delegates from the NAACP met there in 1932 intending to dedicate a plaque in Brown’s honor. In a speech at that meeting titled “The Use of Force in Reform,” Du Bois expressed few compunctions about the use of violence: Brown, he said, “took human lives … He took them in Kansas and he took them here. He meant to take them. He meant to use force to wipe out an evil he could no longer endure.”

Langston Hughes used poetry rather than oratory to address African American readers as he invoked the lingering memory of John Brown. Hughes, whose grandmother had been married to one of the Black conspirators killed in the raid, celebrated “John Brown / Who took his gun, / Took twenty-one companions / White and black, / Went to shoot your way to freedom.” Hughes recalled that his grandmother had preserved her husband’s bullet-ridden shawl. As a small boy, he was sometimes wrapped in it. “You will remember / John Brown,” Hughes insisted.

But, fittingly, given his defining commitment to nonviolence, Martin Luther King Jr. remained silent on Brown. Even as the keynote speaker at a centennial observance of Brown’s raid, King did not mention the man once. The place of violence in the centuries of struggle for Black freedom has been long contested, and by the mid-1960s, King faced growing demands from Black activists urging forceful resistance to white threats and assaults instead of the Gandhian passivity that underpinned his philosophy. Malcolm X regarded Brown as “the only good white the country’s ever had.” The Black Power movement that challenged King’s vision of a Beloved Community could claim deep roots.

Barack Obama reflected the long tradition of Black appreciation for Brown in his 2006 book, The Audacity of Hope. Brown’s “willingness to spill blood,” Obama said, demonstrated that “deliberation alone” would not suffice to end slavery. “Pragmatism,” he concluded, “can sometimes be moral cowardice.”

As a nation, we are unable to get over John Brown. And as a nation, we have not figured out what violence we will condemn and what we will celebrate. I found myself unspeakably moved as I stood before Nat Turner’s Bible in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. At the same time, I am horrified by the violence of the January 6 rioters and by what I regard as widespread threats to the rule of law. We pride ourselves on being a country with a written Constitution that sets peaceful parameters for government. Yet the Supreme Court established by that Constitution has issued rulings providing that the citizenry may be armed not just for recreational hunting, but with weapons, including assault rifles, that are frequently purchased with an eye toward resisting that very government. Lawmakers walk the floors of the Capitol with pins shaped like AR-15s in their lapels. The rule of law seems historically and inextricably enmeshed in the tolerance—even the encouragement—of violence.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, antislavery Americans like the Secret Six turned to what Higginson—with a keen awareness of the oxymoron—called conscientious lawbreaking. Douglass came to embrace the legitimacy of violence, but recognized it as justified “only when all other means of progress and enlightenment have failed”—and only when there is a “thing worse than” violence that makes it necessary.

The existence and endurance of our nation has depended on that careful discernment, on that conscientiousness, in deciding when we truly face a “thing worse than.” It is not merely a historical question. A deep-seated ambivalence about violence defines us still.

This article appears in the December 2023 print edition with the headline “The Men Who Started the Civil War.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.