In the late 1890s, Wilmington, North Carolina, a port city between the Atlantic’s barrier islands and the banks of the Cape Fear River, became an island of hope for a new America.

Residents of the city’s thriving Black community made themselves a political force, exercising the rights of citizenship guaranteed to them after the Civil War by the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Across the South, such activity had triggered deadly white violence against Black voters, organizers and officeholders in the decades since the war. But in Wilmington, a city of 20,000, the votes of 8,000 Black men helped a rare biracial “Fusion” alliance elect candidates of both races.

Three of the 10 aldermen were Black. The city had Black health inspectors, postmasters, magistrates, and policemen, albeit under orders not to arrest anyone white. The county coroner, jailer and treasurer were Black, as was the register of deeds. Black business people pooled their money in three Black-owned banks. Families a generation removed from enslavement owned their homes and read a local Black newspaper.

As modern-day Wilmingtonian Tim Pinnick, a genealogist, put it, “Things functioned the way they were meant to function as a result of Emancipation.”

Planning a Coup

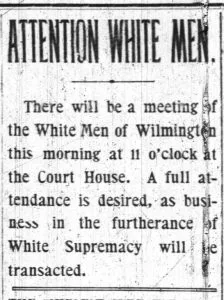

The Wilmington Messenger

But if Wilmington looked to some Americans like a model for the South, powerful white leaders, including the president of Wilmington Cotton Mills Company, the editor of the Raleigh News and Observer, and the chairman of the state Democratic party, could not abide it. They set out to topple what the newspaper editor labeled “Negro rule.”

One hundred and twenty-five years ago, on November 10, 1898, a shocking coup d’etat was executed.

The plotters had set the stage by creating what they called the “White Supremacy Campaign.” They printed falsehoods about Black men preying on white women and stockpiling guns. They targeted the Fusion officeholders and the Black newspaper, summoned militias and white vigilantes known as Red Shirts, and terrorized Black voters at the polls.

“If you see the negro out voting tomorrow, tell him stop,” one of the leaders, former Confederate Colonel Alfred Moore Waddell, told a gun-waving white audience on the eve of Wilmington’s 1898 election. “If he doesn’t, shoot him down. Shoot him down in his tracks.” Mr. Waddell vowed to “choke the current of the Cape Fear River” with Black bodies if he had to.

On November 10, Red Shirts, militiamen, and white mobs surged through Wilmington’s streets and massacred 60 or more Black men. “They gave their lives to vote,” said Hesketh “Nate” Brown, a retired New York City transit manager whose great-great-grandfather, Joshua Halsey, tried to flee the militiamen.

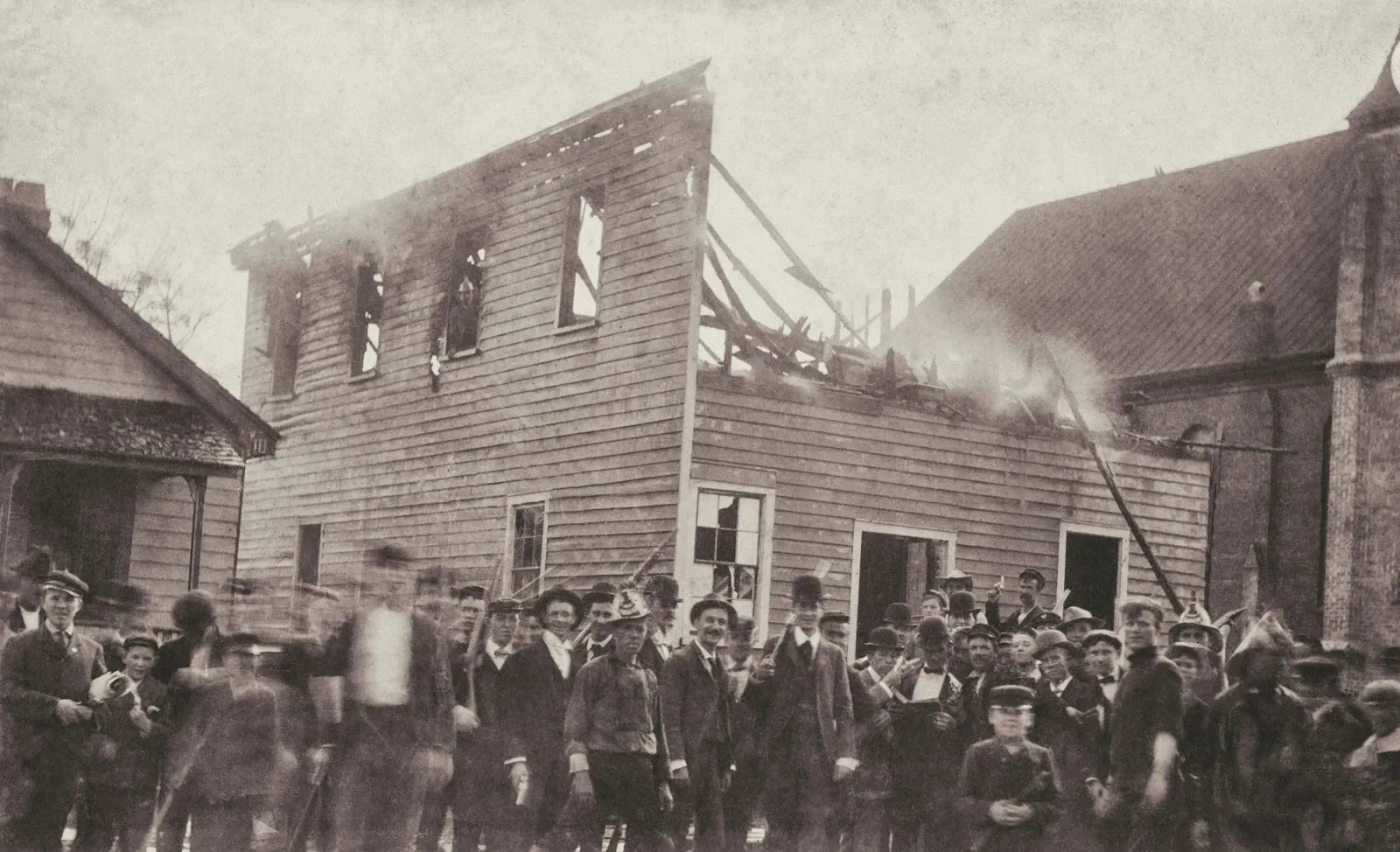

The remains of the office of the Black-owned newspaper The Daily Record after it was burned in the Wilmington coup and massacre, November 10, 1898. (McCool/Alamy)

The Red Shirts torched the Black newspaper’s office, posed for pictures in front of its smoking ruins, installed Mr. Waddell as mayor, and sent hundreds of Black residents fleeing into the woods. Some ran west toward the river; others, east to the Black cemetery. Athalia Howe was 12 when her family and others took refuge in Pine Forest, a cemetery that dated back to the period before Emancipation. It was said that families sheltered next to graves of their loved ones.

Uncovering a History of Racial Injustice

For years no one in Ms. Howe’s family said much about those events, as her great-granddaughter, Cynthia Brown, told The Washington Post. But one day, when she was about eight years old, a distant look filled her great-grandmother’s eyes and she grabbed Ms. Brown’s wrist.

“If it ever happens again, run!” Ms. Brown remembered her shouting. “Don’t let it happen to you!”

Ms. Brown set out to discover what “it” was.

So did Mr. Pinnick, the Black schoolteacher from Illinois who learned of the coup in recent years when he retired to Wilmington. And Nate Brown, the retired transit manager who found his great-great-grandfather’s name in an 1898 newspaper clipping about the “Race War.” (The article blamed Black “aggressors.”) And Sonya Patrick-AmenRa, who counts among her ancestors four soldiers of the United States Colored Troops who helped win the Civil War.

Now, Mr. Brown, Ms. Brown (they are not related), Mr. Pinnick, Ms. AmenRa, and other Wilmingtonians, along with ministers, activists, authors, educators, and a documentary filmmaker whose ancestor aided the plotters, are helping change the historical narrative.

Over the last two decades a school and park named after leaders who directed the murder of dozens of Black people have been renamed. Community activists have set out to learn the names of everyone who was killed and every Black Wilmingtonian who survived the 1898 massacre. They are marking the coup’s 125th anniversary, November 10, with a week of events that include “racial-equity and trauma training,” documentary film showings, and descendants’ stories.

“There is a need to focus on that horrible day to understand it,” Mr. Pinnick said. “And yet, it’s a testimony to surviving that the story should be told.”

For nearly a century the story was told falsely—in textbooks, clippings and memoirs that cast the horrific violence as a spontaneous “riot” and the plotters as heroes who restored racial order to Wilmington.

In 2006, a state-commissioned report debunked the longstanding false narratives about Wilmington’s history.

Even so, Deborah Dicks Maxwell, president of the county’s NAACP chapter, said many local residents still don’t know about it. “This is Wilmington,” she told USAToday last year. “There’s a distance to progress.”

That was evident in the unguarded words of three white Wilmington police officers in 2020, weeks after George Floyd’s killing. A routine audit of patrol-car videotapes revealed the longtime officers discussing killing “f—ing n—s.”

A civil war was coming, Officer Michael Piner said. “We are just gonna go out and start slaughtering them f—ing n—s.” The officers told investigators they had been “venting” and blamed the “stress of today’s climate in law enforcement.”

Wilmington’s first Black police chief fired them in his first week on the job.

Their words were “painful, hurtful,” Chief Donny Williams, a Wilmington officer for nearly three decades, told NPR. “Being from this community, and then working alongside these people for so long, so just hurt—and not just me.”

A Legacy of Political Violence

The full toll of the 1898 massacre and the political legacy it created is still not known.

Estimates of the number of Black people killed range from dozens to hundreds. The state’s 2006 study described the coup in detail and blamed all levels of government for not intervening; it said Black merchants and workers “suffered losses after 1898 in terms of job status, income, and access to capital.” Black businesses moved or closed. Some 2,100 Black residents fled. Black literacy rates plunged.

By the turn of the century, Southern states were using poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses to deny Black men the right to vote, which the Fifteenth Amendment had guaranteed them since 1870. Between 1896 and 1902, the number of Black voters registered in North Carolina fell from 126,000 to 6,100. Wilmington did not elect another Black candidate until 1972.

The violence in Wilmington was not unique. Historians and EJI researchers have documented at least 34 instances of mass violence during Reconstruction where scores of Black people were murdered by white mobs intent on reestablishing white supremacy and resisting Black political participation. It is a history that is not well known but is critically relevant for understanding the continuing struggle for racial justice and the many obstacles that still remain.

Confronting History

Hesketh Brown has tracked down the deed for the home that his great-great-grandfather, Joshua Halsey, who was born before Emancipation, owned at 812 North Sixth Street in Wilmington. David Zucchino’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2020 book, Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy, described what happened there on November 10, 1898: A rumor of gunfire from a Black dance hall caused white militiamen to hunt for Mr. Halsey, searching house to house until someone gave them his address.

One of Joshua and Sallie Halsey’s four daughters—Mary, Susan, Satira and Bessie—saw the militiamen marching toward the house and begged her father, who was said to be deaf, to flee.

He “ran out the back door in frantic terror to be shot like a dog by armed soldiers ostensibly sent to preserve the peace,” a white neighbor wrote in her diary.

Jars of sandy soil from the spot where Mr. Halsey died were collected in 2021 as part of EJI’s Community Remembrance Project. One jar has a place of honor 500 miles away, in the library of Mr. Brown’s home in Queens.

Another jar was part of a ceremonial burial for Mr. Halsey in 2021. After attending the event on that bitterly cold November day, Mr. Brown visited the Cape Fear River. “I just pictured myself being one of those people many years ago—stuck between that river and armed racists and needing to choose,” he said. “It was the first time I felt anger.”

He and Tim Pinnick want to tell the story of 1898. “I want my legacy here to be that I reconnected people, or connected them to their legacy—their great-grandfather lived next door to Joshua Halsey, or around the corner, or a newspaper account connects them, or a marriage document,” Mr. Pinnick said.

He knows how long the truth of what happened went unwritten. Not anymore.

“Someone’s going to write your history,” Mr. Pinnick said. “You can let someone else write it, or you can write it.”