The uncertain legality of paying reparations for slavery and its legacies came into focus last week when the U.S. Supreme Court rejected racial preferences in college admissions nationwide. But while some see the ruling as a major setback for the reparations movement, it isn’t likely to deter its advocates, who say that redress for racial discrimination would not be based strictly on race.

The same day the Supreme Court declared the admissions practices at Harvard College and the University of North Carolina unconstitutional, Kamilah Moore, head of the California task force at the forefront of the national reparations effort, announced on Twitter that the cause is not affected by the decision: “Our reparations recommendations are not race-based, but rather are based on lineal descent.”

It’s a subtle distinction stemming from the California Reparations Task Force’s razor-thin 5-4 vote last year to restrict eligibility for reparations only to California residents who qualify by lineal descendant – either from an enslaved African American, or from a free African American person living in the United States prior to the end of the 19th century. That eligibility criterion will exclude several hundred thousand black people living in California – namely Caribbean, African, and South American black immigrants who arrived in this country in the 20th century.

On the same day the court ruled, the California task force had rolled out an ambitious reparations program for an estimated 2 million black residents, containing more than 100 proposals, including free college tuition, a guaranteed income program, and cash payments that could exceed $1 million for some eligible African Americans.

Task force members repeatedly stated that their damning historical analysis of American racism, and their proposed remedies, are intended to serve as a blueprint for the entire nation to adopt in atonement for what they see as the original sin of slavery and its discriminatory legacies, such as segregation, redlining, and mass incarceration.

The totality of the demands – which would cost California taxpayers an estimated $500 billion to $800 billion if enacted as proposed – is calculated to show that colorblind policies are woefully inadequate for the task of remedying a centuries-long catalog of historical injustices. Indeed, the task force’s report, exceeding 1,000 pages and drawing on international human rights precedents, reads like a case brought before an international human rights tribunal, putting American society on trial for crimes against humanity.

“For those reactionaries who say slavery is old news and the time for reparations has passed, well, you know what, I’ve been a civil rights lawyer for 20 years and I say show me the statute of limitations on mass genocide,” said task force member Lisa Holder at the panel’s final meeting last month. “Show me the statute of limitations on the world’s greatest crime against humanity and show me the statute of limitations on accountability for original sin.”

California’s reparations agenda is now in the hands of state legislators, who will have to decide which, if any, of the recommendations will become law and state policy and which will be shelved. But even before the Supreme Court ruled that using race as a factor in college admissions is unconstitutional, courts had struck down race-based and identity-based preferences – such as a federal $4 billion debt relief program for non-white farmers, and California laws imposing gender quotas and diversity mandates on corporate boards.

At the same time, California voters in 2020 resoundingly reaffirmed the state’s 27-year statewide ban on racial preferences in state government hiring, contracting and in college admissions – known as Proposition 209.

Lawsuits are virtually assured, as reparations skeptics consider eligibility by lineage to be a proxy for race. What’s more, one of the California Reparations Task Force’s 100-plus recommendations would repeal Prop 209, which was upheld by 57% of voters in a 2020 referendum. If that happens, the action would provoke the advocacy groups that had formed for the express purpose of keeping racial preferences out of state government.

“First and foremost, this is a legal matter. It will be challenged, if not by us, then by someone else,” said Wenyuan Wu, executive director of the California for Equal Rights Foundation, a lead group in the 2020 effort upholding Prop 209; it is now suing San Francisco to block that city’s guaranteed income programs for transgender people and for racial minorities.

Against the task force report’s quasi-judicial tone of moral indictment, opponents are expected to challenge some of the historical claims as distortions or one-sided, not unlike the critical response to the similarly themed New York Times 1619 Project published four years ago. UCLA law professor Richard Sander, who has spent his career researching the downsides of racial preferences, said the task force report is infused with Critical Race Theory, reducing complex history to simplistic explanations.

“A big challenge is going to be to put out an accurate counter-narrative,” Sander said. “One valuable thing from this process is the public can see what the critical race studies worldview and agenda is. This report is the distilled ideology. I hope that it will prompt a serious intellectual response.”

Such responses might cite recent studies indicating that redlining – a practice of excluding risky neighborhoods from home lending programs and other financial services — may have impacted more white people than black people, even if blacks were disproportionately affected because of relative poverty and because of racial animus. That historical perspective has been taken up by Columbia University linguistics professor John McWhorter, a social commentator and author of the 2021 book, “Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America.”

Likewise, the task force heard tearful testimony about black residents losing their properties to government seizures, and the report documents the decimation of thriving black neighborhoods, displacing thousands of residents, to clear space for highways and other public projects. Critics say that these stories, however true, omit the numerous examples of eminent domain actions that disenfranchised white property owners, thus distorting public perceptions by focusing only on one race.

William Jacobson, clinical professor of law at Cornell Law School and president of the Legal Insurrection Foundation, which runs conservative websites, said the task force presumes every black person is a powerless victim who deserves compensation – precisely the sort of crude stereotyping the Supreme Court majority has rejected. Jacobson further said that calculating only harms without considering “the other side of the ledger” – like government assistance or other benefits someone’s parents or grandparents may have accrued over a lifetime – is a dishonest moral calculus.

“They’re asking for a lot. They’re asking for what would obviously bankrupt the state,” said University of San Diego law professor Gail Heriot, who helped lead the movement to defeat racial preferences in 2020 as co-chair of the Californians 4 Equal Rights/No on Prop 16, and in 1996 co-chaired Yes on Proposition 209, which implemented the state’s ban on racial preferences.

“Reparations of this kind will likely lead to inter-racial and inter-ethnic strife – just the opposite of what the California’s leaders should be trying to do,” she said. “It’s unlikely to go down well with the people who are paying the taxes for this.”

Glenn Roper, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation, a conservative public interest law practice that challenged the Biden administration’s debt-relief program for non-white farmers, said the California Reparations Task Force report presents a radical challenge to the constitutional principle of equal protection. He said the Pacific Legal Foundation’s clients have in the past challenged the legality of government programs that have “nibbled around the edges” of the equal protection principle, but the California reparations project is of a different scale altogether.

“This would be a sweeping overhaul of the whole equal protection project,” Roper said. “It’s really going to be a pivotal test whether equal protection, colorblindness and race neutrality can withstand the moment.”

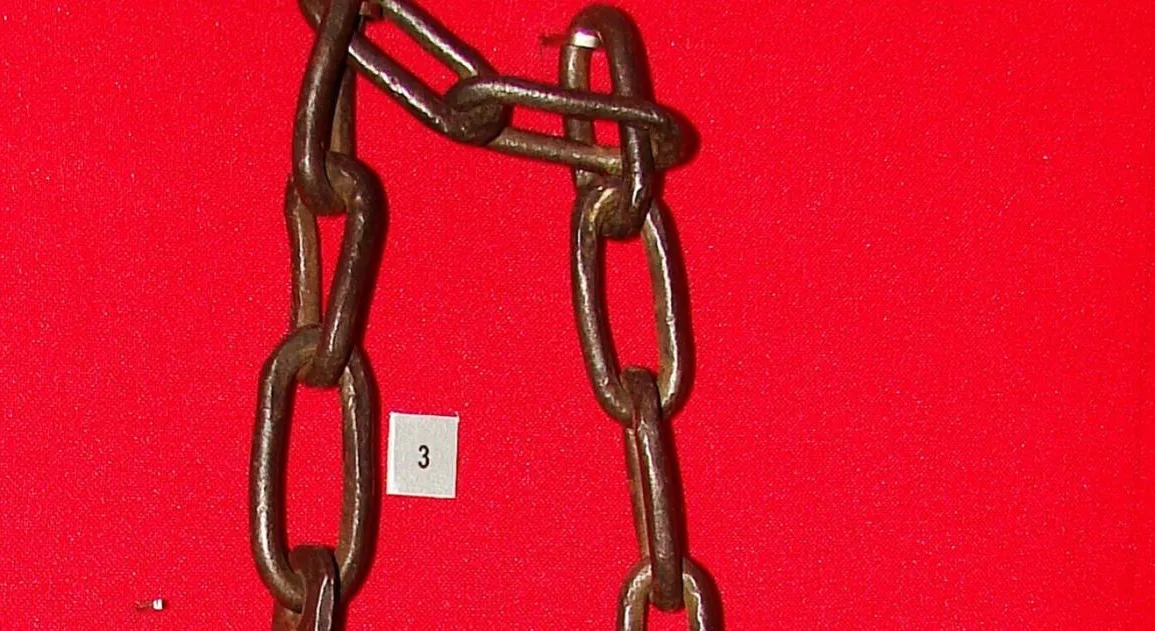

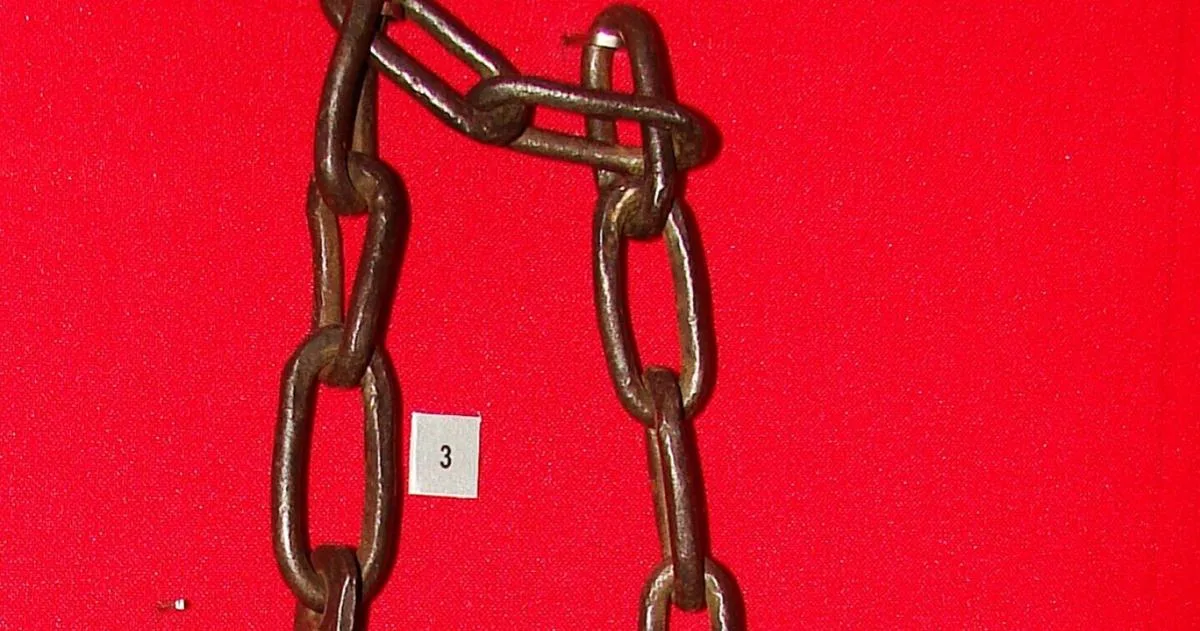

The task force’s reparations report and proposals are a culmination of more than two years of testimony and emotional public hearings in which African American citizens invoked the sufferings of their ancestors, and speakers exclaimed: “Cut the check! Pay the debt! We need cash!”

The task force hearings emphasized public and expert opinions that strengthened the case for reparations, but the matter is now before lawmakers who represent voters who twice upheld Proposition 209.

In deciding which provisions to adopt, California’s Democratic-controlled legislature faces a plethora of thorny questions from the public: If an African American resident has black ancestors who owned slaves, should that person be eligible for reparations? Should there be an income cutoff or sliding scale for affluent African Americans? Should there be restrictions on how black recipients spend their reparations money, just as there are limits on how government agencies and nonprofits spend taxpayer dollars? Should the focus of government be to assist all Americans who are struggling or left behind, rather than prioritizing one ethnic group?

Basing reparations on lineage rather than race was advised by University of California, Berkeley, School of Law dean Erwin Chemerinsky, who last year told the task force there was a “strong argument” that limiting reparations to black people with black ancestry in this country before the year 1900 would be legally defensible, as opposed to awarding reparations to all black people, including black immigrants who may have experienced racial discrimination in this country.

Chemerinsky drew a comparison between reparations for African Americans and other types of reparations. For example, the U.S. government awarded reparations to Japanese Americans forced to live in internment camps during World War II, but the payments went to people who had suffered a specific injury, not for being generally harmed by racial discrimination.

The Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948 offered about $37 million in compensation for real and personal property that Japanese internees had lost. In 1988, Congress voted to extend an apology and pay $20,000 to each Japanese American survivor of the internment, paying more than $1.6 billion to 82,219 eligible claimants. Upon signing the legislation, President Reagan declared that in so doing, the United States government was officially admitting a wrong and reaffirming “our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.”

During March 2022 discussions about eligibility, divisions among the task force members spilled out into the open, highlighting the legal quandary of doing reparations in a U.S. legal framework that restricts or prohibits race-based policies.

“I want to start with what I consider to be an irony,” said task force member Cheryl Grills, a Loyola Marymount University psychology professor whose professional interests include community psychology and African psychology, focusing on African-centered treatment modalities. “Europe and the United States concocted this thing called race to define and control us,” Grills said, “and now we find ourselves being restricted from using the very thing they concocted to liberate ourselves from the legacy of the systems of oppression that they created.”

Grills further warned: “Providing reparations only for those who can prove their descendancy from enslaved Africans is yet another win for white supremacy because it dismisses and devalues the harms done to African descendants not enslaved here but who were injured by slavery due to their blackness once they entered the shores of America.”

Another task force member, veteran civil rights activist Amos Brown, who joined the Freedom Riders and was arrested at a lunch counter in 1961 with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., urged the panel to be realistic and practical.

“Why set up ourselves to be involved in a legal battle?” Brown pleaded with his colleagues. “We know very well in the state of California, because of Proposition 209, which has not been repealed, you cannot have race-based activities and legislation.”

The core contention of the California Reparations Task Force is that decades of systematic anti-black policies in housing, healthcare, education, and policing, much of it documented in the past 100 years, prevented the accumulation of family wealth and the inter-generational transfer of wealth, resulting in present-day racial wealth gaps that require race-conscious policies to reverse. Such historical arguments have been popularized by best-selling race writers like Michelle Alexander, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Nikole Hannah-Jones and Ibram X. Kendi, resulting in a conceptual shift to thinking of racism as a societal problem and a societal responsibility.

Their ideas are spreading, especially in liberal jurisdictions. The State of New York recently passed a bill to create a reparations task force and officials in New Jersey and Vermont have indicated they too plan to address the issue, while more than a dozen municipalities are implementing local programs. According to the online “redress map” of the African American Redress Network, a joint project of academics at Columbia University and Howard University, there were more than 460 local “repair” efforts underway between 2019 and 2022 at businesses, museums, land trusts, universities and municipalities to redress the effects of historical racism; the remedies included housing vouchers, scholarships, commemorations, memorializations, and apologies. Linda Mann, project co-founder and a professor of international and public affairs at Columbia, said the total now is close to 550.

Even if the current legal climate, as signaled by the Supreme Court decision, spells a generational setback to the reparations effort, “at some point the country is going to have to reckon with this,” she said.

Mann said she agreed 100% with the sentiment expressed in the 2021 book, “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story,” that there is absolutely nothing black people can do on their own to get out of poverty – not getting married, not getting an education, not saving more, not buying a home – that would overcome four centuries of “racialized plundering.”

“The disparities are so significant that honestly the only way to bridge them is through some kind of reparative justice,” Mann said. “The structural aspect hasn’t changed. It’s an integral part of our country.”

Task force member Holder told The New York Times that without government intervention to dismantle structural racism, “this continues in perpetuity.” According to her bio on the California Reparations Task Force web site, Holder is a civil rights lawyer, racial justice scholar, and an equity consultant.

It’s a perspective foundational to the reparations movement, one that conveys a bleakness, pessimism and fatalism that some Americans find deeply disturbing.

“We’ve gone from the bright optimism of the civil rights era, to the peevish political correctness of the 1990s, and on to the Age of Wokeness in which young African Americans are being told that they can’t possibly achieve, because everything about the world is rigged against them,” Heriot said. “It’s highly destructive.”