Las Vegas officials are gathering community feedback as they explore the possibility of building a state-of-the-art African-American museum and cultural center as part of their ongoing work to help revitalize the west side.

The project is loosely tied to the Historic Westside district, a historically Black neighborhood that thrived during the 1960s but has struggled with disinvestment in recent decades. The area is bordered by Owens Avenue in the north, U.S. Route 95 to the south, Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard to the west and Interstate 15 to the east, and is part of the HUNDRED Plan, or the Historic Urban Neighborhood Design Redevelopment Plan.

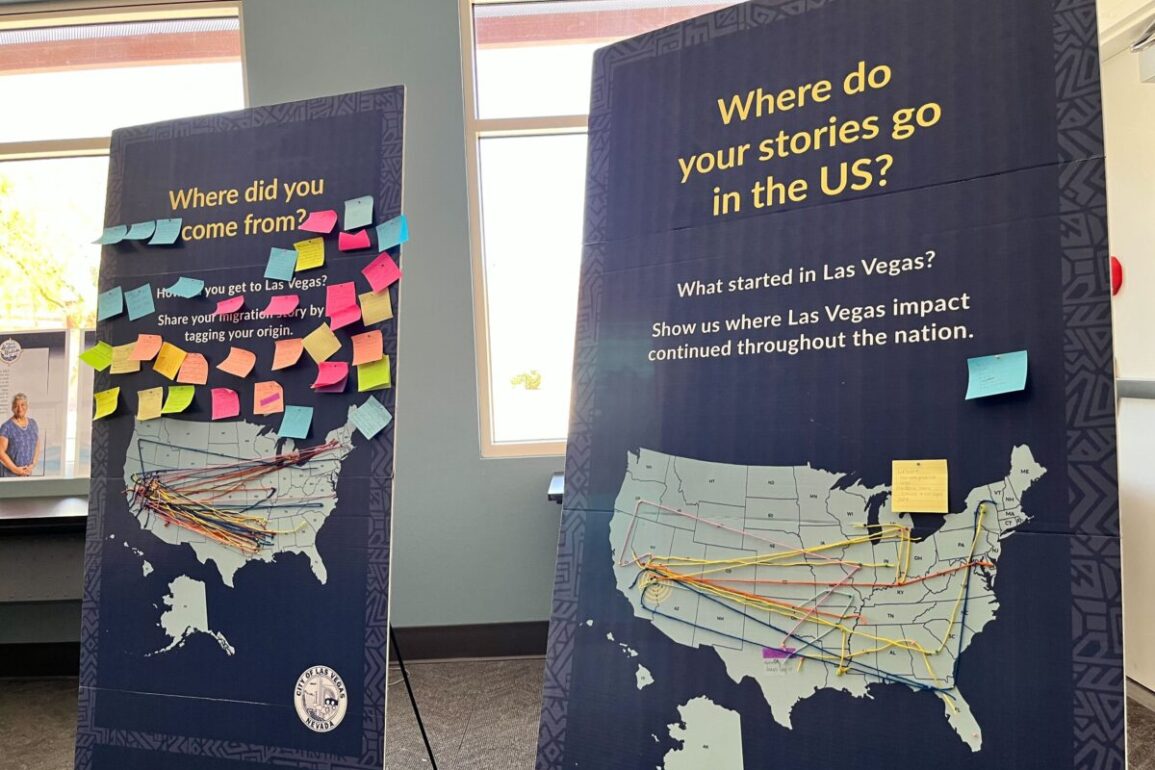

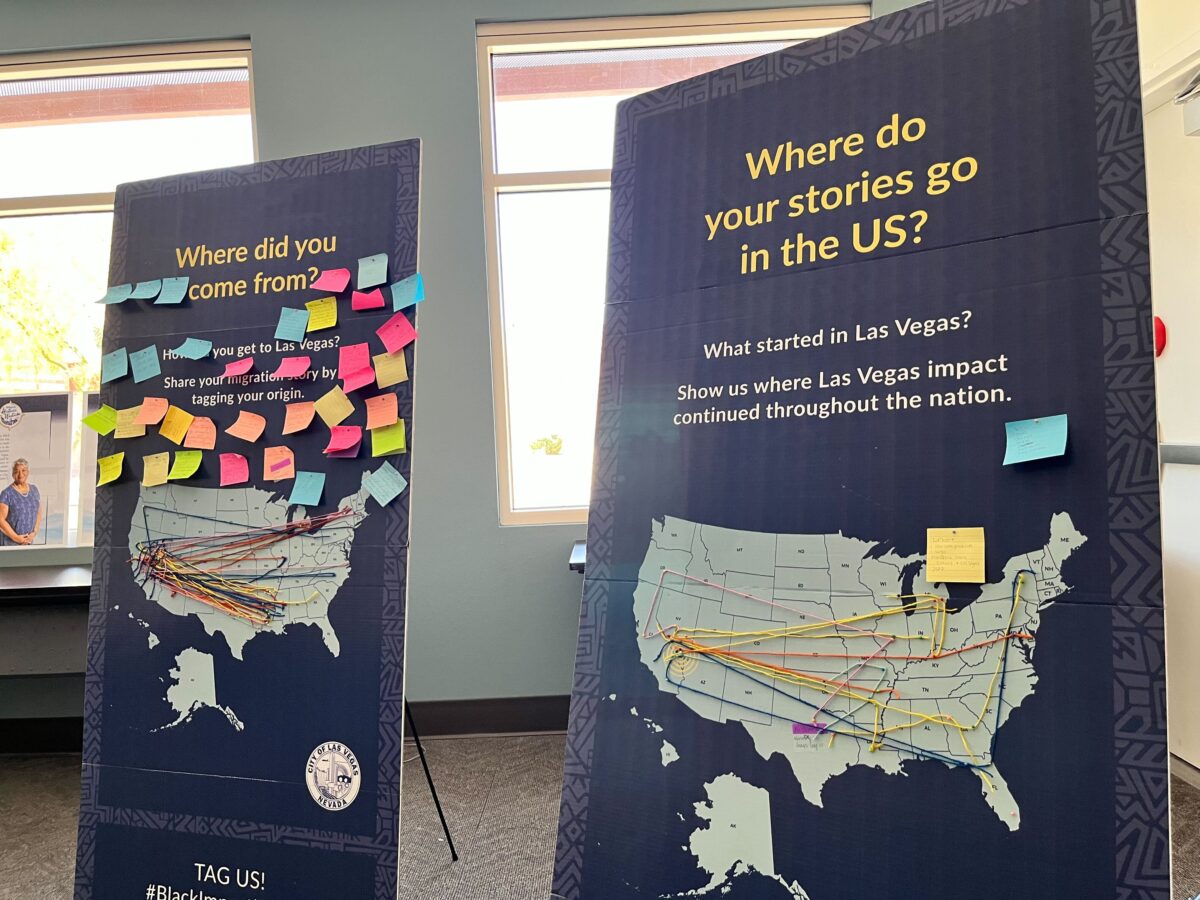

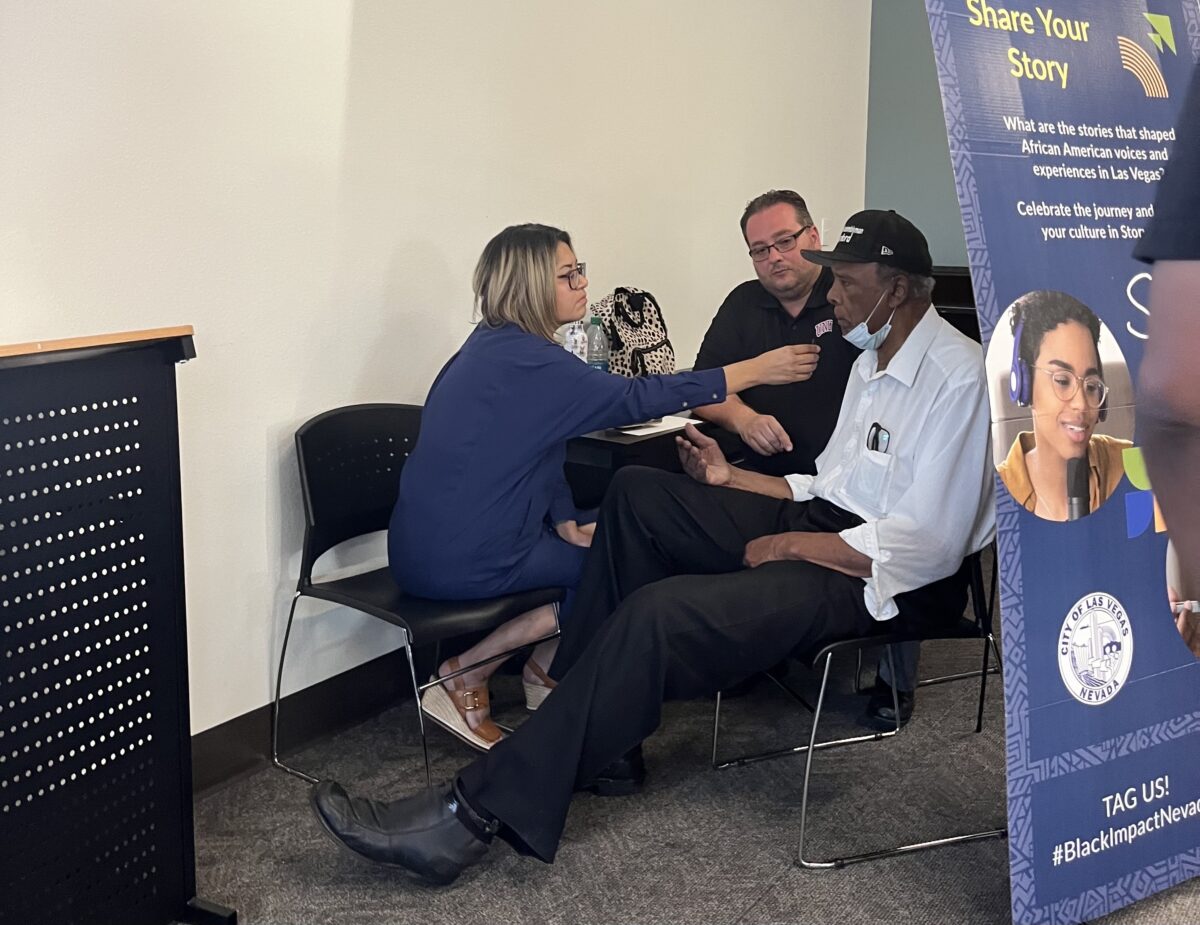

During the second of three listening sessions that took place in June, residents shared oral histories through one-on-one interviews, filled out a survey and contributed to interactive posters that lined the room with maps to display where they migrated from, the places they have visited in Nevada and other details about their family origin and history.

Organizers also showcased prototypes of museum offerings to prompt ideas about what residents might want to see in the museum and cultural center, including contemporary art galleries, historical and future-oriented exhibitions, community activations (or marketing experiences that generate awareness), a performance venue, landmark sculptures and installations. Attendees were surveyed to identify “the local narrative” and cultural assets that will bring economic power to the area.

“Oftentimes, communities like ours don’t even know what makes our magic, magic,” said data scientist Maya Ford, CEO of FordMomentum, a Houston-based communications firm that is working on the project, in an interview during the event. “And so we’re here to present a mirror. We do that through a series of exercises that help people tell us ‘I see myself there, I don’t there. That’s me. That’s not me.”’

Organizers behind the discussions were hired by the City of Las Vegas and include Las Vegas-based businesses and people who helped bring the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., online. Images were propped up of local ambassadors of the project including pictures and quotes from North Las Vegas Mayor Pamela Goynes-Brown, Clark County Libraries Executive Director Kelvin Watson and Mario Berlanga, owner of Mario’s Westside Market, a grocery store that serves the neighborhood.

Ford said the museum will take on elements from the past, present and future to align with the Las Vegas market. The project is still in the discovery phase, without a budget or location.

“Another part of the discussion is where could it be located?” said Shaundell Newsome, owner of Las Vegas-based SUMNU Marketing. “Is it a building, or is it a neighborhood? What is it like?”

The event comes nearly two years after city leaders and national figures from African American museums met to talk about the development, which is part of a larger master plan for the Historic Westside.

Ford described the future Las Vegas African American museum project as a measure of justice, stating that African American communities have not traditionally had the ability to control their own cultural assets.

She said her work is not designed to shy away from racial injustices and that her strategy to discover the hidden uniqueness of Las Vegas’ Black community will mainly focus on extrapolating the mindset, skills and people from data collected at listening sessions. Ford said it takes tools to uncover these details because they are often woven into movements that combat racism and injustices.

“When we see blight, it’s so personal, but we don’t know that it’s systemic,” she said about the Historic Westside. “We don’t know that the tools that were used to get to that, are being used exactly the same way in cities across the nation … but we have a tool to break right through that, for the element that’s unique.”

A range of museum types

During a September 2021 meeting, leaders hosted a public forum and presentation to share the varied African American museum concepts from around the country, inviting public input as the implementation of the HUNDRED Plan pressed forward. The conversation ended with a lot of skepticism toward an international museum concept that would aim to attract locals and tourists alike.

Residents feared that local stories of triumph or racial justice would be lost; that the location might be outside of the Historic Westside district, which is a criticism of the site of Legacy Park, which honors Black community leaders, and that the museum might not come to fruition at all.

“By all accounts, this is one of the most important and complicated projects to come out of the plan,” Tammy Malich, leader of social innovation at the City of Las Vegas, said about the HUNDRED Plan during the 2021 meeting.

The meeting was moderated by Las Vegas City Councilman Cedric Crear of Ward 5, where residents hope the museum will go. Other presenters included George Davis, former director of the California African American Museum (CAAM); Anna Barber, former senior major gift officer for the Smithsonian Museum and fundraiser for the National African American History Museum in Washington D.C., and Ford.

“We got some heavy folk in the room working on this project,” Crear said about the “professional historic consultants.”

The museum consultants went over potential sizes for the museum that ranged from 44,000 square feet to 450,000 square feet; costs to build, which ranged from $460,000 to $700 million; fee structures, which included free admission concepts that rely on federal funding and others with prices ranging from $6 to $7 dollars, and permanent collections ranging from 5,000 objects to 40,000.

“Seventy percent of the overall annual operating budget is federal appropriations,” Barber said about the National African American History Museum, which has a $40 million annual operating cost. “Our collections were primarily donated through private citizens, which really made the museum very, very special and personal.”

Presenters also went over the different types of concepts and how they differ from one another, such as historical sites that include preserved homes and permanent structures, archives, community centers that focus on local stories, museums that hold artifacts and historical documents, and science, nature or geographical history-focused centers.

Davis said costs can increase based on storing certain art pieces and retaining permanent art collections, and that Black art has recently “gone up exponentially in value,” after being traditionally left out of mainstream museums and galleries.

“CAAM had a lot of works from very well-known artists, that were really mostly well-known in the Black community,” he said. “And now they’re getting more mainstream [attention]. And we became a generous lender to a lot of institutions with a traveling [art exhibition] called ‘”Soul of a Nation.’”

The discussion came after Crear and then-Clark County Commissioner Lawrence Weekly released an updated rendering of the HUNDRED Plan in 2020 to alert people that leaders were moving forward with the revitalization strategy using new resources.

Since then, several new developments have been launched, including a street project to reinvigorate Jackson Avenue — which was once known as the Westside Strip — that broke ground in December, the College of Southern Nevada workforce development center at the Historic Westside School, an 84-unit housing development planned for Jackson Avenue, a MGM-backed urban farm in James Gay Park and plans geared toward the rebuilding and relocation of the West Las Vegas Library.

“The community said ‘We would love to see some culture in our community,’” Crear told attendees during the 2021 museum presentation. “So we took that back. And one of the first steps is to go out and find subject matter experts who have done projects like this, of this size.”

Shea butter, healing rooms and concerns

At a listening session last month, residents shared many ideas about what should be showcased at a local African American museum and cultural center, including a statue that could be seen from the Las Vegas Strip made in the likeness of Ruby Duncan, a veteran activist in Las Vegas who fights for the welfare of poor people. Other ideas included developing a stunning building and landscape that resembles Africa or creating a cultural campus where people can enjoy an outside space.

Attendees also discussed how food might come into play, ranging from fine dining, to restaurants that center around vegetables that traveled with Black people from West Africa such as cornbread, okra, rice and tomatoes, to reaching back in Las Vegas history with the recreation of Hamburger Heaven, which was built in 1955 on the west side and torn down in 2011.

“I heard someone say they wanted our center to smell like shea butter,” said Amaya Edden, organizer for SUMNU Marketing. “I’ve also heard people say they wanted to have resource centers around it … to help the community.”

Edden said each listening event garners a lot of engagement from the community, and that Friday’s gathering was the fourth of many to come.

She said over the last several weeks she’s heard ideas from residents including a quiet “healing room” for people. Attendees also encouraged leaders to think about features that would help the homeless population in the area.

Edden also said when it came to the topic of slavery, some people did not want to reach back that far.

“They were saying that sometimes we are stuck in the trauma that happened,” she said. “So they wanted something to uplift the generations.”

Kimberly Estell, 55, has lived in Las Vegas for about 30 years. At the listening session, she told The Nevada Independent that she hopes the museum expands opportunities such as apprenticeships in the STEAM field for youth that focus on science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics.

Her friend, Tee-azha Akin, 31, who was born and raised in Las Vegas, said she is looking forward to local artists being lifted up by the new museum.

“I like what they have laid out, especially when it comes to the community activations and the art, because I would love to see Vegas really flourish as an art space,” Akin said.

Most concerns regarding the project that were shared at the 2021 event and in a June listening session centered on the thought that an international museum might not showcase the stories about local movements, that the emphasis would be placed elsewhere and leave out local historians.

TaShika Lawson, 39, who was born and raised in Las Vegas, said it was hard for her to get on board with the project, voicing concerns about an African American museum that already exists in the Historic Westside — Walker African American Museum and Research Center on West Van Buren Street, which is run by Gwen Walker.

“Because she has a museum that she’s already approached the city about – for it to actually become something that’s bigger and more expansive and does real justice and brings life back to Jackson Street,” Lawson said about Walker at the recent listening event. “And although she may not have had a big plan, it’s no less than what we’re seeing here. It was a dream.”

In a July interview with The Nevada Independent, Walker, 66, said that after at least 10 years of seeking resources from city officials to refurbish and expand her museum, she felt blindsided and betrayed by the exploration of a “world class” African American museum, because originally the HUNDRED Plan included a revitalization of Walker African American Museum.

Walker said she has built up her collection for over 50 years, which has been used by UNLV students who study African American history, and that it includes at least 50,000 artifacts, with pieces that date back as far as the 1800s. She said she is not on board with the plans to build a second history museum, especially after feeling pushed aside by city officials.

“I was floored for about three weeks,” Walker said about the moment she learned of the second museum proposal. “I almost couldn’t function. I was so hurt and so upset. I cry every time I think about it.”