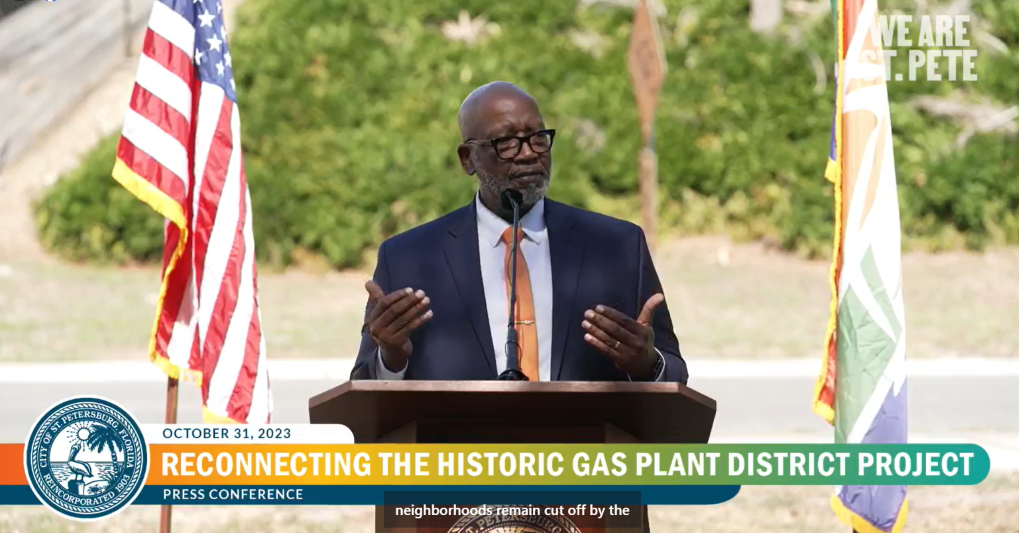

Mayor Ken Welch and U.S. Rep. Kathy Castor held a joint press conference on Tuesday on the corner of Fifth Avenue South and 16th Street to highlight a grant the City of St. Petersburg recently submitted to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

ST. PETERSBURG — John Mellencamp’s 1983 hit “Pink Houses” summed up the egregious efforts the United States government undertook to thwart integration when he sang:

There’s a Black man with a black cat

Livin’ in a Black neighborhood

He’s got an interstate runnin’ through his front yard

You know he thinks he’s got it so good

With the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, highways such as Interstate 275 and 175 in St. Pete were built through Black communities, decimating them by “creating physical barriers to integration or to physically entrench racial inequality,” said Debra Archer, president of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Those intentional practices took place nationwide, targeting thriving Black communities. Interstate 275 took with it homes, hundreds of Black businesses, churches, schools — the community. So why would officials target African-American neighborhoods?

Well, highways were being built just as courts around the country were striking down traditional tools of racial segregation, such as racial zoning to keep Black people out of white spaces, Archer said.

Highway development sprung up when integration in housing was on the horizon. And so, Archer posits, “Highways were sometimes built right on the former boundary lines that we saw used during racial zoning, sometimes community members asked the highway builders to create a barrier between their community and encroaching Black communities.”

This was certainly the case in St. Pete. Interstate 175 cut the former Gas Plant neighborhood and other Black communities off from downtown, along with one-way streets still plaguing the downtown area.

On Tuesday, Mayor Ken Welch and U.S. Rep. Kathy Castor held a joint press conference on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 16th Street South to highlight a grant the city recently submitted to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

“All across America right now, communities are reexamining mistakes that were made over 50 years ago when the interstate highway system was planned,” said Castor, noting that I-275 bifurcated the working communities of south St. Pete from downtown.

She pointed out the redlining of neighborhoods and how reexamining the area is needed to repair those historic mistakes.

President Biden’s $2 trillion plan to improve America’s infrastructure and racism ingrained in historical transportation and urban planning was rolled out in 2021 to

“reconnect neighborhoods cut off by historic investments,” according to a statement by the White House in 2021. It also looks to target “40 percent of the benefits of climate and clean infrastructure investments to disadvantaged communities.”

The city is requesting $1.2 million from Biden’s Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods Community Planning Grant Program to plan the Reconnecting the Historic Gas Plant District Project to help improve safety, access, mobility, air quality, and economic opportunities in south St. Pete.

The Reconnecting the Historic Gas Plant District Project aims to remediate the impacts of constructing I-175 in the late 1970s that uprooted many families of historic African-American neighborhoods in south St. Pete, including the Gas Plant District.

Approximately 4,000 individuals were forced to relocate, and 2,700 Black families and businesses were displaced. The totality of the project’s expected outcomes will benefit disadvantaged communities.

“Today, adjacent neighborhoods remain cut off by the walled limited access highway and several one-way streets, including Eighth and Dr. M.L.K. Jr Streets, which have access ramps on I-175,” said Welch. “The transportation facilities have created persistent barriers to community connectivity, particularly to adjacent south St. Pete communities and neighborhoods.”

This grant funding will support an 18-month community-informed planning project for the two-way conversion and lane reallocation of Eighth and M.L.K. Jr. Streets to improve access, safety, mobility, and connectivity. The plan will also address the environmental and economic burdens impacting surrounding neighborhoods.

Now, in addition to addressing injustices of the past and disparities of the present, this project will support the plan for the equitable redevelopment of this site by reconnecting neighborhoods that were divided by the interstate to downtown and other areas of the city. The projects will benefit those separated neighborhoods.

City Council Vice Chairperson Deborah Figgs-Sanders said the city plans to create pathways that embrace inclusivity, enhance accessibility for pedestrians and those with mobility challenges along with prioritizing environmental justice.

“Through innovative planning, green infrastructure and the commitment to sustainability, we will improve our air quality, alleviating the burden of pollution disproportionately affecting our community,” Figgs-Sanders said.

Whit Blanton, the executive director of Forward Pinellas, said he has a commitment next year from the Florida Department of Transportation to undertake an action plan for I-175 to determine the best course of action for improvements to that corridor. He mentioned the plan will also encompass the study of Eighth and M.L.K. Jr. Streets.

“I’m really happy that FDOT was able to advance the study of I-175 so that it can be timed with the planning and redevelopment of the historic Gas Plant District; that’s key,” he said.

Terri Lipsey Scott, executive director of the Woodson African American Museum of Florida, gave some history on the highway system devasting Black and Brown communities.

“And just the first two decades of construction, over 1 million individuals nationwide found themselves displaced from their homes and businesses. This was not a mere coincidence; it was a calculated move,” Scott said, noting that eminent domain was invoked, private properties were seized and hundreds of communities across the nation were razed, cutting some communities in half.

Mayor Welch spoke about his grandfather’s woodyard, his great-aunt’s restaurant and businesses lining both sides of 16th Street South being razed when I-175 came through.

He feels the highway is a visual reminder of what happened to the community. Even after the interstate came through, there was still a small vestige of the thriving community until the city’s “pursuit of a light industry that later became the pursuit of baseball.”