By Tamara Shiloh

The name Henry O. Flipper shines as a symbol of resilience and triumph over adversity. Born to enslaved parents, Isabella and Festus Flipper, on March 21, 1856, in Thomasville, his early life was marked by the dark shadows of slavery. However, Flipper’s indomitable spirit and thirst for knowledge led him on a path that would make him a trailblazer in breaking racial barriers.

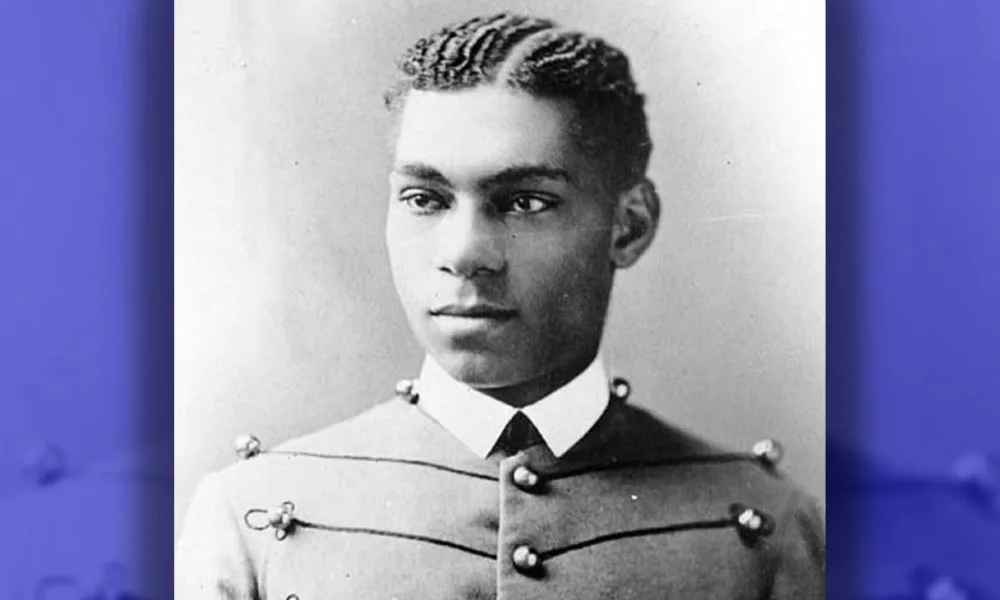

After the Civil War, Flipper’s education was supported by the American Missionary Association. He later attended Atlanta University, becoming the fifth African American to receive an appointment to the prestigious U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1873. His enrollment came at a time when white cadets held prejudiced attitudes, making the environment hostile for African Americans. Despite the challenges, Flipper endured, graduating in 1877, thus becoming the first African American to achieve this monumental feat.

His experiences at West Point, both the triumphs and tribulations, were documented in his 1878 book, “The Colored Cadet at West Point,” shedding light on the discrimination he faced and the determination that carried him through.

Following graduation, Flipper was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army and served with the 10th Cavalry, an African American unit known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

However, his promising career was unjustly derailed in 1881 when he was framed by white officers on charges of embezzlement while stationed at Fort Davis, Texas. Though found not guilty of the major charge, he was still dishonorably discharged, casting a shadow over his reputation. Undeterred, Flipper devoted the rest of his life to fighting for the restoration of his good name.

As a civilian, Flipper’s talents extended far beyond the military realm. He excelled as an engineer, surveyor, and translator, showcasing his proficiency in Spanish by translating critical texts on Mexican tax, mining, and land laws. His work took him to Mexico, where he served as a mining engineer for over a decade.

When he returned to the U.S., he worked for Senator Herbert Fall, advising him on Mexican politics. When Fall became Secretary of the Interior in 1921, Flipper worked with him in Washington, D.C.

Two years later, Flipper traveled to Venezuela where he worked as an engineer in the oil industry, retiring eight years later in Atlanta.

He wrote his memoirs in 1916, offering a candid account of his life, which would later be published posthumously in 1963 as “Negro Frontiersman: The Western Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper.”

The efforts of his descendants were rewarded in 1976 when the Department of the Army finally granted him an honorable discharge, posthumously restoring his good name. In the same year, a bust of Flipper was unveiled at West Point, immortalizing his legacy. President Bill Clinton granted him a full pardon in 1999, a testament to his enduring impact on American history.

He died in 1940, and was initially buried in a cemetery near Atlanta, but his remains were exhumed and again laid to rest in his native Thomasville in 1978, where the post office was named in his honor.

Today, West Point awards a commendation in his name to the graduating senior who demonstrates exemplary leadership, self-discipline, and perseverance in the face of adversity.